3546

Chasing the Dot: Diffusion-Weighted MR Spectroscopy with Spherical Tensor Encoding1Cardiff University Brain Research Imaging Centre (CUBRIC), School of Psychology, Cardiff University, Cardiff, United Kingdom, 2Department of Mathematics, University of Bern, Bern, Switzerland, 3School of Computer Science and Informatics, Cardiff University, Cardiff, United Kingdom, 4Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc. Tarrytown, New York, NY, United States, 5Magnetic Resonance Methodology, Institute of Diagnostic and Interventional Neuroradiology, University Bern, Bern, Switzerland, 6Translational Imaging Center, sitem-insel, Bern, Switzerland, 7High-field MR Centre, Department of Biomedical Imaging and Image-guided Therapy, Medical University of Vienna, Vienna, Austria

Synopsis

Keywords: Gray Matter, Spectroscopy, Spherical Tensor Encoding, Diffusion, Metabolites

Diffusion-weighted MR spectroscopy (DW-MRS) can measure diffusion properties of cell type-specific and intracellular metabolites. However, for advanced microstructure modeling, diffusion of brain metabolites has to be measured at specific length scales and with specific structural sensitivity. To this end, new diffusion encoding strategies have been developed, but not all have found their ways into DW-MRS. In this work, we fill this gap for spherical-tensor-encoding (STE), providing the first evidence that useful diffusion metrices of human brain metabolites can be quantified by combining DW-MRS, STE, and ultra-strong gradients.Introduction

Diffusion-weighted MR spectroscopy (DW-MRS) can measure the diffusion properties of cell-type specific intracellular metabolites and be sensitized to specific microstructural features. The latter is achieved via choice of sequence design (e.g., spin-echo at short to intermediate diffusion-times; stimulated-echo at long diffusion-times) or diffusion-encoding strategy[1],[2]. Many diffusion-encoding strategies have been translated from Diffusion-Weighted MR Imaging (DWI) into DW-MRS (e.g., pulsed or oscillating gradients, double-diffusion encoding)[3]-[5]. However, spherical-tensor-encoding (STE) has not. This is particularly useful for inferring on cellular microstructure in isotropic compartments[1]. By using a spherical and isotropic sampling of the diffusion-tensor simultaneously along all gradient axes, relatively high b-values can be achieved even at short diffusion-times. For instance, at an averaged diffusion-time of 6.9ms (Fig. 1) and a free metabolite diffusivity of 0.3∙10-3mm2/s the characteristic length scale is only 2μm. This allows diffusion to be quantified in highly restricted compartments like small dendrites, organelles, mitochondria, or fat droplets and provide elevated sensitivity to cytoplasmic viscosity (e.g., accumulation of macromolecular neurofibrillary tangles in Alzheimer’s disease). Here we provide the first demonstration of combining STE with DW-MRS at ultra-short diffusion-times in human brain.Methods

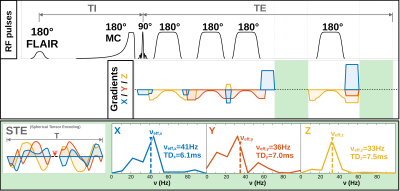

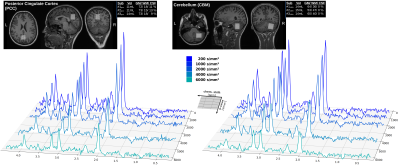

Data acquisition: Measurements were conducted on a 3T Connectom-A MR scanner (Siemens Healthcare) with 300mT/m per axis using a 32-channel receive headcoil. MPRAGE images (isotropic 1mm3) were used for voxel positioning and tissue segmentation(Fig. 2). A semiLASER (TE/TRtrig: 114/2800ms) sequence was extended with STE[4](Fig. 1). STE waveforms were created with the NOW-toolbox (symmetric; total duration: 91.3ms [including 8.3ms RF-spacing], 1st-order motion-compensated, Maxwell-compensated: 100mT2/m2∙ms) and applied at b=200, 1000 2000, 4000, 6000, 8000s/mm2 (Gmax,x/ Gmax,y/ Gmax,z: 143.6/ 168.9/ 157.3mT/m)[6],[7]. The diffusion-times of the STE waveform along each axis were derived from the frequency spectrum to be 6.1/7.0/7.5ms (average: 6.9ms, Fig. 1)[8]. Cardiac triggering was applied at every 3rd RR-cycle. FLAIR was used for CSF suppression and metabolite-cycling (MC) to measure water and metabolite diffusion simultaneously[9].Subjects: Six healthy subjects (31.6±5.7yrs, 3 female) were recruited in agreement with the local ethical guidelines. The VOI was placed in the Posterior Cingulate Cortex (PCC,12.0±1.7mL) in three subjects and in the Cerebellum (CBM, 14.3±0.6mL) in the others(Fig. 2).

Data processing: Beyond coil-channel combination, phase-offset, frequency-drift and eddy-current correction, the inherent water reference was used for motion-compensation to restore signal amplitudes to a reference level presumably unaffected by motion[9].

Analysis, Fitting and Modeling: A neural network with U-NET like architecture was trained on a set of synthetic data for denoising[10]. Metabolic basis-sets for Asp, tCr, GABA, Glc, Gln, Glu, Gly, tCho, GSH, mI, Lac, NAA, NAAG, PE, sI and Tau were simulated with MARSS[11] considering RF-pulse profiles and sequence chronograms. Basis-sets were imported into FiTAID[12] for sequential linear-combination modeling and resulting metabolite amplitudes used for ADC fitting in MatLab.

Results and Discussion

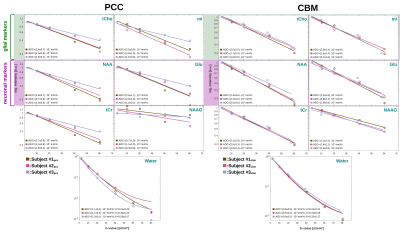

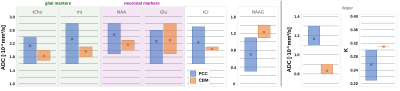

Spectral quality: The spectral quality presented in Fig. 1 allows all major brain metabolites to be identified readily. Moreover, expected stronger eddy-current artifacts could be avoided by using the inherent water reference for direct phase-distortion correction. The spectra at the highest b-values of 8000s/mm2 were excluded from the analysis due to strong variations in the water reference most likely a result of increased table variance.Metabolite diffusion: Metabolite ADCs, presented in Fig. 3, show an overall strong agreement with a monoexponential Gaussian diffusion model, even for low concentration (mI) or heavily J-coupled (Glu) ones. A high inter-subject agreement between ADCs is found in CBM and more variance in PCC (particularly subject#3pcc reproducibly shows slower metabolite diffusion). The diffusion of NAAG is only trustworthy in CBM with a higher WM concentration(Fig. 2). Diffusion is by average slower in CBM than PCC(Fig. 4).

Water diffusion: While the kurtosis model has high uncertainties in PCC, a good agreement is found in CBM(Fig. 3). The trend towards faster metabolite diffusion in PCC is reproduced by water(Fig. 4). This is supported by a higher kurtosis in CBM indicating more restriction (to note: water diffusion at these short diffusion-times should be unaffected by water exchange).

Conclusion

The presented metabolite ADCs agree with Monte-Carlo simulations of STE in realistic cell samples we reported previously[13]. The inter-subjects consistency of metabolite diffusion in CBM suggests a higher biophysical heterogeneity, where alterations might serve as biomarker for brain pathology. Recent results applying STE in DWI have found a highly restricted “dot-compartment” in CBM where diffusion is considerably slower than in other brain regions[14]. Even though our results show by average slower metabolite diffusion as well, no particular metabolite stick out and the observed difference is most likely related to the higher WM content. This suggests either that the dot-compartment originates from extracellular contribution without metabolites, is restricted to small organelles (e.g., mitochondria) with short metabolite T2 and, in turn, inaccessible at TE of 114ms, or that even higher b-values than used here are required to reach the non-Gaussian diffusion regime.This work demonstrated for the first time that DW-MRS with STE and ultra-strong gradients can measure metabolite diffusion at ultra-short diffusion-times and relatively high b-values.

Acknowledgements

AD is supported by a Swiss National Science Foundation Fellowship (SNSF #202962). KS is supported by a UKRI Future Leaders Fellowship (MR/T020296/2). DKJ is supported by a Wellcome Trust Strategic Award (104943/Z/14/Z).References

[1] Afzali M, Mueller L, Szczepankiewicz F, Jones DK, Schneider JE. Quantification of Tissue Microstructure Using Tensor-Valued Diffusion Encoding: Brain and Body. Front Phys 2022, 10:1-11.

[2] Shemesh N et al. Conventions and nomenclature for double diffusion encoding NMR and MRI. Magn Reson Med 2016, 75:82-7.

[3] Ligneul C, Valette J. Probing metabolite diffusion at ultra-short time scales in the mouse brain using optimized oscillating gradients and ‘short’-echo-time diffusion-weighted MRS. NMR Biomed 2017, 30: e3671.

[4] Döring A, Kreis R. Magnetic resonance spectroscopy extended by oscillating diffusion gradients: Cell-specific anomalous diffusion as a probe for tissue microstructure in human brain. Neuroimage 2019, 202: 116075.

[5] Vincent M, Palombo M, Valette J. Revisiting double diffusion encoding MRS in the mouse brain at 11.7T: Which microstructural features are we sensitive to?. Neuroimage 2019, 207: 116399.

[6] Szczepankiewicz F, Westin CF, Nilsson M. Gradient waveform design for tensor-valued encoding in diffusion MRI. J. Neurosci. Methods 2021, 348: 109007.

[7] Szczepankiewicz F, Sjölund J. Cross-term-compensated gradient waveform design for tensor-valued diffusion MRI. J Magn Reson 2021, 328: 106991.

[8] Parsons EC, Does MD, Gore JC. Temporal diffusion spectroscopy: Theory and implementation in restricted systems using oscillating gradients. Magn Reson Med 2006, 55:75-84.

[9] Döring A, Adalid V, Boesch C, Kreis R. Diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance spectroscopy boosted by simultaneously acquired water reference signals. Magn Reson Med 2018, 80:2326-38.

[10] Rösler F, Döring A. MRspecNET. 2022. https://github.com/frank-roesler/MRspecNET

[11] Landheer K, Swanberg KM, Juchem C. Magnetic resonance Spectrum simulator (MARSS), a novel software package for fast and computationally efficient basis set simulation. NMR Biomed 2019, 11:1-13.

[12] Adalid V, Döring A, Kyathanahally SP, Bolliger CS, Boesch C, Kreis R. Fitting interrelated datasets: metabolite diffusion and general lineshapes. Magn Reson Mater 2017, 30:429-448.

[13] Döring A, Afzali M, Kleban E, Kreis R, Jones DK. Realistic simulations of diffusion MR spectroscopy: The effect of glial cell swelling on non-Gaussian and anomalous diffusion. Intl. Soc Mag Reson Med 2021, 3401.

[14] Tax CMW, Szczepankiewicz F, Nilsson M, Jones DK. The dot-compartment revealed? Diffusion MRI with ultra-strong gradients and spherical tensor encoding in the living human brain. Neuroimage 2020, 10: 116534.

Figures