3541

¹H fMRS detects changes in dorsal anterior cingulate cortex glutamate driven by inhibitory control1Translational Neuroscience Program, Wayne State University School of Medicine, Detroit, MI, United States, 2Wayne State University School of Medicine, Detroit, MI, United States, 3Psychiatry and Behavioral Neuroscience, Wayne State University School of Medicine, Detroit, MI, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Psychiatric Disorders, Spectroscopy, Inhibitory Control

¹H fMRS was used to quantify changes in dACC glutamate evoked during excitatory and inhibitory motor control. The two response modes demanded non-selective responding (motor control with excitation) or selective responding (motor control with inhibition). dACC glutamate was significantly increased (relative to a resting baseline), regardless of response mode. These functional responses (uncoupled from hemodynamics) demonstrate that ¹H fMRS can be successfully used to reveal glutamate related mechanisms of the dACC reflecting changes in the excitatory neurotransmission drive.

Introduction

Inhibitory control can be thought of as the ability to selectively withhold ‘prepotent’ motor responses, and this involves the processes of both motor control and inhibition. Poorer inhibitory control has been implicated or suspected in a variety of conditions, such as obsessive-compulsive disorder, substance use disorder, and a poor ability to maintain weight loss1–3. fMRI studies have demonstrated a central role of the dorsal anterior cingulate cortex in inhibitory control4–6, but limitations of the BOLD signal preempt the ability of fMRI to be informative about underlying mechanisms, particularly the putative role of glutamatergic and GABAergic neurons. This limitation is challenging because systems are implicated in the balance between excitatory and inhibitory drive in neural circuits7. In comparison, 1H fMRS can assess how specific changes in excitatory neurotransmission drive glutamate under specifically controlled task conditions8 and can elucidate possible mechanistic bases in ways that fMRI cannot. Here, we investigated whether ¹H fMRS can detect changes in dACC glutamate during task conditions with and without inhibitory motor control.Methods

Data were acquired in 33 healthy control subjects (15 F and 18 M; 12-20 yrs; mean age: 17.0±2.6 yrs).1H fMRS was conducted on a Siemens 3T Verio system with a 32-channel volume head-coil. MPRAGE T1-weighted structural images were collected, after which a single-voxel was defined in the midline of the dACC (17x20x12mm3). Voxel placement utilized the AVP approach9. Following voxel placement, FASTESTMAP was utilized for B0-field shimming. The visually guided motor task was consistent with previous studies1 and involved epochs of “Non-Selective” and “Selective” response modes. Each mode was conducted as a separate 1H fMRS scan, with 32s task epochs (n=6) and 16s rest epochs. A visual fixation crosshair was utilized as a baseline control (13 consecutive 16s measurements). In the Non-Selective mode, participants were presented with a flashing green or red probe (50%/50% distribution, 100% responses) and were instructed to tap when presented with either probe. In the Selective mode, they were instructed to tap only to the green probes (80% distribution) while inhibiting responses to the red probes (20% distribution). Across epochs, probes were presented with either a fixed or pseudorandom inter-stimulus interval (Periodic and Random conditions respectively). Nineteen consecutive measurements with a temporal resolution of 16s were acquired for each mode (PRESS sequence, TR=2.67s, TE=23ms, 6 averages/measurement, scan time= 5:10/mode). The two 1H fMRS spectra in each task epoch were averaged after applying a phase and frequency shift correction followed by quantification using LCModel. A repeated measures generalizing estimating equations (GEE) approach was taken to assess glutamate changes across task conditions (baseline condition, Non-Selective, Selective) (SAS GENMOD; SAS Institute Inc). GEE statistics was also used to assess the main effects of task mode (Selective vs Non-Selective), periodicity (Periodic vs Random) and the task mode-by-periodicity interaction.Results

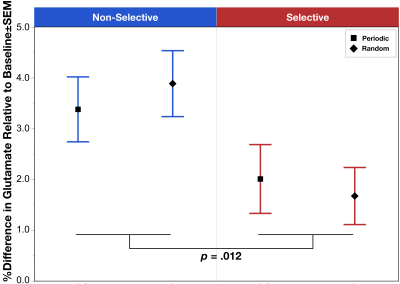

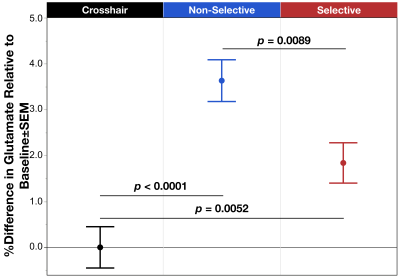

The task condition term was significant (χ2=13.84, p=.012) with post hoc analysis indicating a significant increase in glutamate during Non-Selective (z=4.87, p<.0001) and Selective (z=2.80, p=.005) response modes relative to baseline, as well as a significant increase in glutamate comparing Non-Selective vs Selective (z=2.62, p=.009) (Figure 1). The other model failed to reveal a significant interaction between task mode and periodicity (χ2=.00, p=.98); however, consistent with the above, the task mode term was significant (χ2=6.37, p=.012) demonstrating a lower glutamate during Selective vs Non-Selective (Figure 2).Discussion

We present the first demonstration of significant increases in glutamate during both Non-Selective and Selective motor responses. The effects suggest that ¹H fMRS can detect glutamate changes resulting from a greater excitatory neurotransmission drive. Additionally, results demonstrated a significant difference in glutamate modulation between Non-Selective and Selective motor responses indicating that this push towards greater excitatory drive is relatively less in during Selective inhibitory control. One may speculate that the relatively lower glutamate modulation during Selective motor control may be related to the added function of inhibitory control impacting the E/I drive. This effect was also independent of the periodicity of the stimuli presentation, which demonstrated no differences between periodic vs random in either response mode. Future directions will compare the behavioral task data to the observed changes in glutamate modulation. Taken together, these data indicate that this inhibitory control task can be used in conjunction with 1H fMRS to study the mechanisms underlying known dACC activation, including investigating potential dysfunctions in dACC glutamate modulation implicated in numerous conditions characterized by poor inhibitory control.Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the NIMH under award number R01MH59299 (DRR and VAD), the Children’s Hospital of Michigan Foundation, Miriam Hamburger Endowed Chair, Paul and Anita Strauss Endowment, and by the Lycaki-Young Funds from the State of Michigan.References

1. Friedman, A. L. et al. Brain network dysfunction in youth with obsessive-compulsive disorder induced by simple uni-manual behavior: The role of the dorsal anterior cingulate cortex. Psychiatry Res Neuroimaging 260, 6–15 (2017).

2. Goldstein, R. Z. & Volkow, N. D. Dysfunction of the prefrontal cortex in addiction: neuroimaging findings and clinical implications. Nat Rev Neurosci 12, 652–669 (2011).

3. Miller, A. A. & Spencer, S. J. Obesity and neuroinflammation: A pathway to cognitive impairment. Brain Behav Immun 42, 10–21 (2014).

4. Botvinick, M. M., Cohen, J. D. & Carter, C. S. Conflict monitoring and anterior cingulate cortex: an update. Trends Cogn Sci 8, 539–546 (2004).

5. Paus, T. Primate anterior cingulate cortex: Where motor control, drive and cognition interface. Nat Rev Neurosci 2, 417–424 (2001).

6. Diwadkar, V. A., Asemi, A., Burgess, A., Chowdury, A. & Bressler, S. L. Potentiation of motor sub-networks for motor control but not working memory: Interaction of dACC and SMA revealed by resting-state directed functional connectivity. Plos One 12, e0172531 (2017).

7. Tatti, R., Haley, M. S., Swanson, O. K., Tselha, T. & Maffei, A. Neurophysiology and Regulation of the Balance Between Excitation and Inhibition in Neocortical Circuits. Biol Psychiat 81, 821–831 (2017).

8. Stanley, J. A. & Raz, N. Functional Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy: The “New” MRS for Cognitive Neuroscience and Psychiatry Research. Frontiers Psychiatry 9, 76 (2018).

9. Woodcock, E. A., Arshad, M., Khatib, D. & Stanley, J. A. Automated Voxel Placement: A Linux-based Suite of Tools for Accurate and Reliable Single Voxel Coregistration. J Neuroimaging Psychiatry Neurology 3, 1–8 (2018).Figures

Figure 1. Mean % difference in glutamate relative to the baseline condition across task modes: fixation crosshair, Non-Selective (blue), and Selective (red). Results showed significant difference between the three groups, with the Non-Selective and Selective significantly increased glutamate relative to baseline, though the Selective mode was also significantly decreased compared to the Non-Selective condition. Error bars represent ±SEM.