3531

Dexmedetomidine Administration in a Rat Model of Kaolin-induced Hydrocephalus1National Magnetic Resonance Research Center (UMRAM), Bilkent University, Ankara, Turkey, 2Department of Neurosurgery, Hacettepe University, Ankara, Turkey, 3Department of Histology and Embryology, Hacettepe University, Ankara, Turkey, 4Department of Radiology, Hacettepe University, Ankara, Turkey, 5Department of Radiology, University of California, Davis, Sacramento, CA, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Neuroinflammation, Translational Studies, Hydrocephalus , dexmedetomidine

Hydrocephalus is defined as an abnormal enlargement of cerebral ventricles due to disturbed cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) dynamics. It is characterized by neuroinflammatory processes in the brain parenchyma and CSF, with pathological findings including reactive gliosis, axonal and neuronal damage, and loss of myelin sheaths. The use of anti-inflammatory medications in hydrocephalus may be an effective treatment strategy for neuroprotection. In this study, we used a rat model of hydrocephalus induced by kaolin. We aimed to demonstrate the potential anti-inflammatory and neuroprotective effects of dexmedetomidine on hydrocephalic brains using MRI and morphometric analysis.Introduction

Hydrocephalus is defined as an abnormal enlargement of cerebral ventricles due to disturbed cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) dynamics1. This condition might result from impaired absorption of CSF (communicating type) or obstructions in CSF flow (non-communicating type)2. Depending on the etiology and progression speed of hydrocephalus, a wide range of neurological manifestations- including those associated with high mortality rates- might be observed2.Hydrocephalus is characterized by neuroinflammatory processes in the brain parenchyma and CSF; pathological findings might include reactive gliosis, axonal and neuronal damage, and loss of myelin sheaths3,4. The use of anti-inflammatory medications in hydrocephalus patients may be an effective treatment strategy for neuroprotection5,6.

Dexmedetomidine is an α-2 agonist commonly used for its sedative properties7; moreover, its anti-inflammatory and organ-protective effects were shown in sepsis8,9, neuropathic pain10, and ischemia11, among other pathologies. It was also proposed as a 'glymphatic enhancer'12 due to its effects on glymphatic clearance13 and brain delivery of intrathecal drugs14.

In this study, we used a rat model of hydrocephalus induced by kaolin. We aimed to demonstrate dexmedetomidine's potential anti-inflammatory and neuroprotective effects on hydrocephalic brains using MRI and morphometric analysis.

Methods

Twenty-one adult male Sprague-Dawley rats were used for the experiments. Animals were housed under standard facility conditions. All experimental procedures were approved by the institutional review board. Three experimental groups were studied:1. Sham group – n=7; received an intracisternal saline injection (30 μl)

2. Hydrocephalus control group – n=7; received intracisternal kaolin (25%, 30 μl; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) followed by daily intraperitoneal saline injections for a week

3. Hydrocephalus treatment group – n=7; received intracisternal kaolin (25%, 30 μl; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, USA) followed by daily intraperitoneal dexmedetomidine injections (40 μg/kg/day; Polifarma, Turkey) for a week

Brain imaging studies were conducted on Siemens Magnetom Trio 3-Tesla MRI scanner (Siemens Healthcare, Erlangen, Germany) using a single channel receiver coil adapted for rodent heads. Anesthesia was induced using intraperitoneal ketamine-xylazine (75‐90 mg/kg; 5‐10 mg/kg) injection, and rats were placed in an MRI-compatible animal bed. Brain images were acquired using 3D T1-weighted MPRAGE (TE/TR=3.94/2300 ms, TI=900 ms; 48 slices, NEX=2, image matrix=128×256, FOV=50×100 mm2, 0.4× 0.4 × 0.4 mm3 resolution) sequence. The subjects were scanned twice: two weeks after the intracisternal injections (Day 14) and following the dexmedetomidine injections (Day 22).

Acquired rat brain images were spatially normalized to a population template using ANTS software (http://stnava.github.io/ANTs)15, and non-brain tissues were removed using the artsBrainExtraction tool16. Next, SIGMA rat brain atlas17 and related tissue probability maps were normalized to population template coordinates. Tissue segmentation was performed on the images using the Atropos function of the ANTS toolbox for volumetric measurements. Resulting gray matter (GM), white matter (WM), and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) compartments were modulated with Jacobian determinants of deformation maps acquired during the normalization process to account for overall volume differences. Total voxel intensities were calculated from modulated segmentations; GM, WM, and CSF volumes were calculated for each animal. Statistical comparisons between groups and time points were performed on GraphPad Prism software (version 9; California, USA).

Results and Discussion

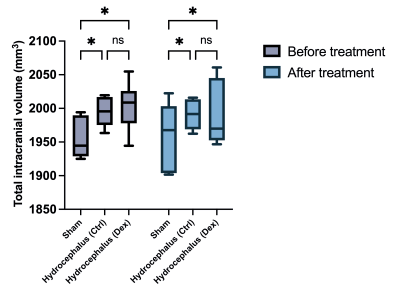

In this study, we aimed to demonstrate the effects of dexmedetomidine administration on a rat model of kaolin-induced hydrocephalus. We hypothesized that the proven anti-inflammatory and organ-protective properties of dexmedetomidine would cause a reduction in CSF volumes of animals with hydrocephalus.Intracisternal kaolin injections reliably induced hydrocephalus phenotype in rats, as seen in anatomical MRI sequences (Figure 1). Morphometry showed statistically significant CSF (Figure 2) and intracranial volume (Figure 3) differences at baseline between hydrocephalus and sham groups.

A week-long treatment with dexmedetomidine (40 μg/kg/day) did not cause a significant reduction in either CSF (Figure 2) or total intracranial volumes (Figure 3) in hydrocephalic animals. Our failure to show significant volumetric changes in response to dexmedetomidine treatment might be due to the short-term use of this medication, insufficient doses, or the severity of the kaolin model itself.

As a continuation of this work, we are in the process of analyzing brain samples from this cohort of animals with histopathological methods. It is also conceivable that the beneficial effects of dexmedetomidine can be detected at the tissue levels rather than the gross anatomical level.

Acknowledgements

No acknowledgement found.References

1. Kahle, K. T., Kulkarni, A. V., Limbrick, D. D. & Warf, B. C. Hydrocephalus in children. Lancet 387, 788–799 (2016).

2. Langner, S. et al. Diagnosis and Differential Diagnosis of Hydrocephalus in Adults. Rofo 189, 728–739 (2017).

3. Karimy, J. K. et al. Inflammation in acquired hydrocephalus: pathogenic mechanisms and therapeutic targets. Nat Rev Neurol 16, 285–296 (2020).

4. Harris, C. A., Morales, D. M., Arshad, R., McAllister, J. P. & Limbrick, D. D. Cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers of neuroinflammation in children with hydrocephalus and shunt malfunction. Fluids Barriers CNS 18, 4 (2021).

5. Goulding, D. S. et al. Neonatal hydrocephalus leads to white matter neuroinflammation and injury in the corpus callosum of Ccdc39 hydrocephalic mice. J Neurosurg Pediatr 1–8 (2020) doi:10.3171/2019.12.PEDS19625.

6. Gualberto, I. J. N. et al. Is there a role in the central nervous system development for using corticosteroids to treat meningomyelocele and hydrocephalus? Childs Nerv Syst 38, 1849–1854 (2022).

7. Barends, C. R. M., Absalom, A., van Minnen, B., Vissink, A. & Visser, A. Dexmedetomidine versus Midazolam in Procedural Sedation. A Systematic Review of Efficacy and Safety. PLoS One 12, e0169525 (2017).

8. Mei, B., Li, J. & Zuo, Z. Dexmedetomidine attenuates sepsis-associated inflammation and encephalopathy via central α2A adrenoceptor. Brain Behav Immun 91, 296–314 (2021).

9. Sun, Y.-B. et al. Dexmedetomidine inhibits astrocyte pyroptosis and subsequently protects the brain in in vitro and in vivo models of sepsis. Cell Death Dis 10, 167 (2019).

10. Shan, W., Liao, X., Tang, Y. & Liu, J. Dexmedetomidine alleviates inflammation in neuropathic pain by suppressing NLRP3 via Nrf2 activation. Exp Ther Med 22, 1046 (2021).

11. Yang, Y.-F. et al. Dexmedetomidine Attenuates Ischemia/Reperfusion-Induced Myocardial Inflammation and Apoptosis Through Inhibiting Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress Signaling. J Inflamm Res 14, 1217–1233 (2021).

12. Persson, N. D. Å., Uusalo, P., Nedergaard, M., Lohela, T. J. & Lilius, T. O. Could dexmedetomidine be repurposed as a glymphatic enhancer? Trends in Pharmacological Sciences (2022) doi:10.1016/j.tips.2022.09.007.

13. Benveniste, H. et al. Anesthesia with Dexmedetomidine and Low-dose Isoflurane Increases Solute Transport via the Glymphatic Pathway in Rat Brain When Compared with High-dose Isoflurane. Anesthesiology 127, 976–988 (2017).

14. Lilius, T. O. et al. Dexmedetomidine enhances glymphatic brain delivery of intrathecally administered drugs. Journal of Controlled Release 304, 29–38 (2019).

15. Avants, B. B. et al. A reproducible evaluation of ANTs similarity metric performance in brain image registration. NeuroImage 54, 2033–2044 (2011).

16. MacNicol, E. et al. Atlas-Based Brain Extraction Is Robust Across RAT MRI Studies. in 2021 IEEE 18th International Symposium on Biomedical Imaging (ISBI) 312–315 (2021). doi:10.1109/ISBI48211.2021.9433884.

17. Barrière, D. A. et al. The SIGMA rat brain templates and atlases for multimodal MRI data analysis and visualization. Nature Communications 10, 5699 (2019).

Figures