3517

White matter hyperintensity shape in relation to long-term small vessel disease progression in community-dwelling older adults

Jasmin A. Keller1, Sigurdur Sigurdsson 2, Mark A. van Buchem1, Lenore J. Launer3, Matthias J.P. van Osch1, Vilmundur Gudnason2,4, and Jeroen H.J.M. de Bresser1

1Department of Radiology, Leiden University Medical Center, Leiden, Netherlands, 2Icelandic Heart Association, Kopavogur, Iceland, 3Laboratory of Epidemiology and Population Science, National Institute on Aging, Bethesda, MD, United States, 4Faculty of Medicine, University of Iceland, Reykjavik, Iceland

1Department of Radiology, Leiden University Medical Center, Leiden, Netherlands, 2Icelandic Heart Association, Kopavogur, Iceland, 3Laboratory of Epidemiology and Population Science, National Institute on Aging, Bethesda, MD, United States, 4Faculty of Medicine, University of Iceland, Reykjavik, Iceland

Synopsis

Keywords: Dementia, Aging, Cerebral small vessel disease

White matter hyperintensity (WMH) shape was recently introduced as a novel small vessel disease (SVD) marker that may provide a more detailed characterization of WMH than volume alone. We aimed to investigate the association between baseline WMH shape and cerebrovascular disease progression over 5 years. A more irregular shape of periventricular/confluent and deep WMH at baseline is associated with increased progression of WMH volume. Moreover, a more irregular shape of periventricular/confluent WMH was associated with occurrence of new microbleeds and new subcortical infarcts at follow-up. Our findings indicate that a more irregular WMH shape is associated with SVD progression.Introduction

Cerebral small vessel disease (SVD) is a strong vascular contributor of cognitive decline and dementia1. Common SVD markers on brain MRI are white matter hyperintensity (WMH) volume, lacunes and microbleeds. Recently, WMH shape was introduced as a novel marker that may provide a more detailed characterization of WMH compared to the most commonly used WMH volume. WMH shape markers have been associated with the occurrence of future stroke and increased mortality in patients with an increased vascular burden2. Moreover, a more irregular shape of periventricular/confluent WMH was associated with an increased long-term risk for dementia3. Since it is unknown whether WMH shape is a predictor of SVD progression, we aimed to investigate the association between baseline WMH shape and progression of SVD markers over 5 years.Methods

Participants & study designData from the AGES Reykjavik study was used in the current study4. FLAIR and T1-weighted brain MRI scans were acquired at baseline from 2002 to 2006 on a 1.5 Tesla Signa Twinspeed system (General Electric Medical Systems, Waukesha, Wisconsin). Five years later, follow-up MRI scans were acquired from 2007 to 2011 with the same protocol. A total of 2297 participants were included in the current study.

WMH shape

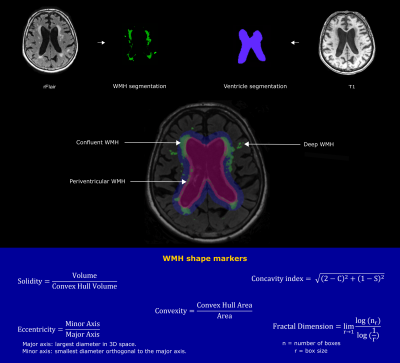

WMH were segmented automatically on registered FLAIR images using the LST toolbox in SPM125. Lateral ventricles were segmented from T1 scans and the ventricle masks were inflated with 3 and 10 mm. The inflated ventricle masks aided WMH classification into periventricular, confluent, and deep WMH (figure 1). WMH shape markers were calculated based on the WMH segmentations. Convexity, solidity, concavity index, and fractal dimensions were determined for periventricular/confluent WMHs6. A lower convexity and solidity, and higher concavity index and fractal dimension indicate more irregularly shaped periventricular or confluent WMH. Fractal dimensions and eccentricity were calculated for deep WMH6. Higher eccentricity and fractal dimensions indicate a more complex shape of deep WMH.

Other SVD markers

Gray matter, white matter, cerebrospinal fluid and WMH volume were segmented automatically with a modified algorithm based on the Montreal Neurological Institute pipeline7. Intracranial volume resulted from the addition of the volumes of gray matter, white matter, cerebrospinal fluid and WMH8. Occurrence of new brain subcortical infarcts and microbleeds was rated by comparing the baseline and follow-up MRI scans9.

Statistical analysis

Solidity and convexity were inverted for the logistic regression analyses to aid comparability of the results. Solidity was multiplied by 100 and natural log transformed due to non-normal distribution. Z-scores of WMH shape markers were calculated to aid comparability. To study the association between WMH shape markers and ΔWMH volume linear regression analyses controlled for age, sex, and ICV were performed. To study the association between WMH shape markers and occurrence of new infarcts and new microbleeds logistic regression analyses were performed, controlled for age and sex.

Results

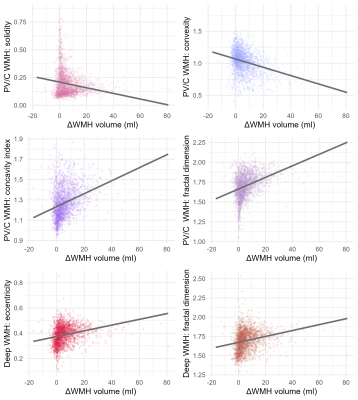

Characteristics of the study sample are shown in table 1. The relation of WMH shape markers and ΔWMH volume at the 5-year follow-up is shown in figure 2. A more irregular shape of periventricular/confluent (solidity, convexity, concavity index, fractal dimension) and deep WMH (eccentricity, fractal dimension) at baseline were associated with increased progression of WMH volume over 5 years (table 2). A more irregular shape of periventricular/confluent WMH (solidity, convexity, concavity index, fractal dimension) was associated with new subcortical infarcts and new microbleeds at the 5 year follow-up (table 3).Discussion

We found that a more irregular shape of periventricular/confluent and deep WMH is associated with increased progression of WMH volume over 5 years. Moreover, a more irregular shape of periventricular/confluent WMH was associated with occurrence of new subcortical infarcts and new microbleeds at the 5 year follow-up. The etiology of WMH in SVD is heterogenous and the pathophysiology remains poorly understood. A more irregular shape of WMH may reflect a more severe underlying etiology of SVD, and as such is subsequently followed by increased progression of SVD related brain changes. This hypothesis is in line with previous post-mortem histopathological studies that showed that a more irregular shape of confluent WMH was associated with more severe brain parenchymal changes compared to the mild and smooth periventricular WMH10,11. In conclusion, our findings indicate that a more irregular WMH shape is associated with long-term SVD progression.Acknowledgements

This research was supported by an Alzheimer Nederland grant (WE.03-2019-08).References

- Gorelick PB, Scuteri A, Black SE et al. Vascular contributions to cognitive impairment and dementia: a statement for healthcare professionals from the american heart association/american stroke association. Stroke. 2011;42(9):2672-713.

- Ghaznawi R, Geerlings MI, Jaarsma-Coes M et al. Association of White Matter Hyperintensity Markers on MRI and Long-term Risk of Mortality and Ischemic Stroke: The SMART-MR Study. Neurology. 2021;96(17):e2172-e2183.

- Keller JA, Sigurdsson S, Klaassen K et al. A more irregular white matter hyperintensity shape is associated with increased long-term dementia risk in community dwelling older adults: The AGES Reykjavik Study. Submitted 2022.

- Harris TB, Launer LJ, Eiriksdottir G et al. Age, Gene/Environment Susceptibility-Reykjavik Study: multidisciplinary applied phenomics. Am J Epidemiol. 2007;165(9):1076-87.

- Schmidt, P. Bayesian inference for structured additive regression models for large-scale problems with applications to medical imaging. (Maximilians-Universität München, 2017).

- Ghaznawi R, Geerlings MI, Jaarsma-Coes MG et al. The association between lacunes and white matter hyperintensity features on MRI: The SMART-MR study. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2019;39(12):2486-2496.

- Zijdenbos AP, Forghani R and Evans AC. Automatic "pipeline" analysis of 3-D MRI data for clinical trials: application to multiple sclerosis. IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging. 2002;21(10):1280-1291.

- Sigurdsson S, Aspelund T, Forsberg L et al. Brain tissue volumes in the general population of the elderly: the AGES-Reykjavik study. Neuroimage. 2012;59(4):3862-3870.

- Sigurdsson S, Aspelund T, Kjartansson O et al. Cerebrovascular Risk-Factors of Prevalent and Incident Brain Infarcts in the General Population: The AGES-Reykjavik Study. Stroke. 2022;53(4):1199-1206.

- Kim KW, MacFall JR, Payne ME. Classification of white matter lesions on magnetic resonance imaging in elderly persons. Biol Psychiatry. 2008;64(4):273-80.

- Fazekas F, Kleinert R, Offenbacher H et al. Pathologic correlates of incidental MRI white matter signal hyperintensities. Neurology. 1993;43(9):1683-9.

Figures

Figure 1. Illustration of the image processing

pipeline. Lateral ventricles were segmented using T1-weighted MRI images.

WMH segmentation was performed on the registered FLAIR (rFLAIR) images. Using

two different inflated ventricle masks (3 mm and 10 mm), WMH were classified

into three types (deep, periventricular and confluent). Based on the resulting WMH

type, different WMH shape markers were calculated using the shown formulas.

Table 1. Characteristics of the study sample. Data

are indicated as mean ± SD or frequency (%). BMI: body mass index; WMH: white matter hyperintensity.

Table 2. Linear regression results of the baseline WMH

shape markers and WMH volume progression over 5 years. The association of WMH shape

markers and ΔWMH volume was determined by linear regression, controlled for

age, sex, and intracranial volume. WMH: white matter hyperintensity. ***p<0.001

Figure 2. Scatterplot showing baseline WMH shape markers

in relation to ΔWMH volume determined at the 5-year follow-up. WMH: white matter hyperintensity; PV/C: periventricular/confluent.

Table 3. Logistic regression results of the baseline WMH shape markers and occurrence

of new subcortical infarcts and new microbleeds over 5 years. The association

of WMH shape and new subcortical infarcts/microbleeds was assessed by logistic

regression, controlled for age and sex. WMH: white matter hyperintensity. **p<0.01; ***p<0.001

DOI: https://doi.org/10.58530/2023/3517