3507

Action execution and observation network: the structural connectome supporting variable force perception1Dept. Brain and Behavioural Sciences, University of Pavia, Pavia, Italy, 2Dept. Mental Health and Dependence, ASST of Pavia, Pavia, Italy, 3Dept. Neuroradiology, IRCCS Humanitas Research Hospital, Milan, Italy, 4Brain Connectivity Center, IRCCS Mondino Foundation, Pavia, Italy, 5NMR Research Unit, Department of Neuroinflammation, Queen Square Multiple Sclerosis Centre, UCL Queen Square Institute of Neurology, University College London (UCL), London, United Kingdom

Synopsis

Keywords: Brain Connectivity, Tractography & Fibre Modelling, Action execution observation network

Inter-individual interaction is at the basis of social life making it crucial to characterize the functional networks subtending action execution (AE) and action observation (AO). We investigated the integrative properties of previously defined AE and AO functional networks in relation to force perception in terms of their underlying structural brain connectivity. We found that both networks show a strong connectivity between areas involved in sensory/force perception and in motor planning. The cerebellum was engaged both in executing the force-related task and in simulating motor responses, supporting the existence of specific brain networks involving the cerebellum in mirroring and mentalizing mechanisms.Introduction

Through social interactions, people create a context that enables survival. Thus, it is crucial to investigate the main neural networks involved in understanding others’ behavior that require the use of mentalizing and mirroring systems. While the first supports the cognitive understanding of mental states1, the latter favours action identification through a neural resonance between action execution (AE) and action observation (AO)2. The action execution-observation network (AEON) is defined as the intersection of functional areas involved in both action execution and action observation. Studying the AEON is useful to investigate motor function, as in the case of a variable power grip task, previously presented3. Different neural systems contribute to generate a certain amount of grip force and control its delivery, with simple (i.e., linear) and complex (i.e., non-linear) functional Blood Oxygenation Level Dependent (BOLD) responses found in cerebral and cerebellar areas3–5. The current study aimed to investigate the integrative abilities of these previously validated AE and AO networks of force perception by defining their underlying structural connectomes and focusing on the role of specific core regions.Methods

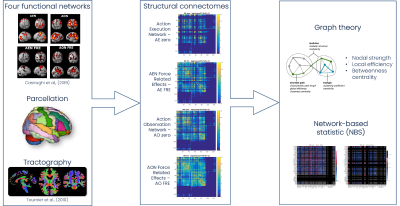

Figure1 reports a scheme of the analysis pipeline.Subjects: Twenty-seven healthy controls (HC) (17 females, 22-35years) were downloaded from the WU-Minn HCP Data – 100 Unrelated Subjects database (http://db.humanconnectome.org).

MRI acquisition: Functional AE and AO networks were derived from previous task fMRI data3. Diffusion-weighted data was acquired with 1.25x1.25x1.25mm3 resolution, b=1000,2000,3000s/mm2, 90 isotropically distributed directions/shell, 18 b0 images and was downloaded together with a co-registered 3DT1-weighted volume.

Functional networks and nodes definition: Four networks were previously defined and validated in MNI152 space3: AE zero – main effect of AE; AE FRE – force related effects during AE; AO zero – main effect of AO; AO FRE – force related effects during AO. To perform brain parcellation and label assignment, a union network, i.e. a mask obtained by adding together all AE/AO networks, was created and overlapped to an ad hoc atlas, comprising of 128 cerebral (AAL6) and cerebellar (SUIT7) labels. Only regions with more than 50 voxels were considered from the intersection between the union network and the atlas and assigned to specific labels.

Connectomics analysis: 30 million streamlines whole-brain anatomically-constrained tractography was performed using probabilistic tractography8. For each of the four AE/AO network, the whole-brain tractogram was intersected with each specific network nodes to obtain the corresponding structural connectome (SC) matrix, obtaining 4 separate SCs for each subject. SC matrices were weighted by the normalized number of streamlines. For each node of each network (AE zero, AO zero, AE FRE, AO FRE) we calculated the weighted nodal strength, weighted local efficiency, weighted betweenness centrality (Brain Connectivity Toolbox, BCT)9, and whether the node belonged to a core or peripheral group on the basis of the number of its connections.

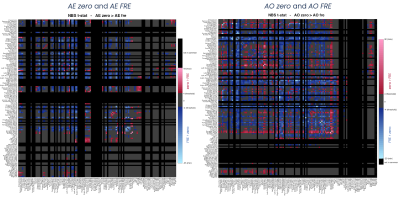

Statistics: Significant differences between networks were calculated considering only those nodes/edges common to pairs of networks (Network-Based Statistic, NBS)10 through t-test. The statistical threshold was set to p=0.05 FDR (false discovery rate) corrected. Direct comparisons were between: (i) AE zero and AO zero, (ii) AE FRE and AO FRE, (iii) AE zero and AE FRE, (iv) AO zero and AO FRE.

Results

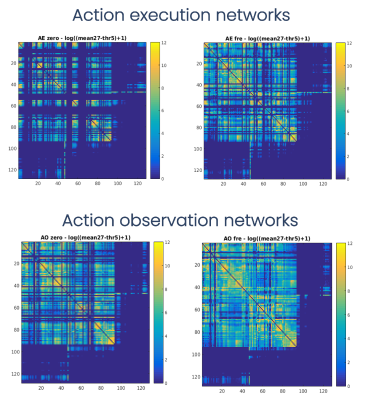

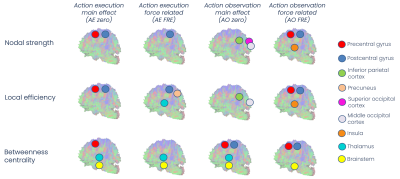

SC matrices (Figure2) showed qualitatively that FRE networks were more connected than zero ones, and the AE FRE network involved more associative regions and cerebro-cerebellar connections compared to the others. For all networks, regions with the highest values of nodal strength, local efficiency and betweenness centrality belonged to the core pool (Figure3). NBS confirmed quantitatively that FRE networks had significantly more connections than zero ones (blue, Figure4) involving more brain regions, while zero networks presented fewer but highly-connected regions, like putamen, occipital cortex and cerebellar CrusI-II (red, Figure4). Further, zero networks showed higher engagement of the cognitive cerebellum (CrusI-II, lobules VIIb-VIIIb) while FRE engaged the motor cerebellum (lobules I-V-IX).Discussion

This is the first work to reveal the structural connectivity subserving AEON. Our results demonstrate that the AEON involved in force perception presents several connections supporting mirroring and mentalizing activity.Mirroring activity may be explained by the fact that all networks presented a high connectivity between areas involved in sensory/force perception and in motor planning, even if AE and AO networks were characterized by different connectivity metrics. Regions such as the precentral gyrus, postcentral gyrus, thalamus, insula, temporal and parietal areas were part of a core pool of nodes, meaning that such regions might be fundamental in both variable force application (i.e. action) and force perception including inferring the force level applied by others (i.e. observation).

The cerebellum is shown to be a very important structure considering that cerebellar involvement was particularly prominent in FRE networks, both supporting the execution of a task requiring control of the applied force (AE FRE) and the engagement in simulation (AO FRE), potentially being recruited for both mirroring and mentalizing mechanisms.

The AEON should be investigated using tractograms, along with corresponding functional data, to resolve circuit dynamics using Dynamic Causal Modelling, and in neurological diseases presenting a relevant disruption of AE, like Parkinson’s disease that presents abnormal activity of basal ganglia, or ataxia that originates from cerebellar damage, or even multiple sclerosis where focal lesions may affect different AEON tracts.

Acknowledgements

Data were provided by the Human Connectome Project, WU-Minn Consortium (PI: David Van Essen and Kamil Ugurbil; 1U54MH091657) funded by the 16 NIH Institutes and Centers that support the NIH Blueprint for Neuroscience Research; and by the McDonnell Center for Systems Neuroscience at Washington University.

ED and FP receive funding from H2020 Research and Innovation Action Grants Human Brain Project (#785907, SGA2 and #945539, SGA3). ED receives funding from the MNL Project “Local Neuronal Microcircuits” of the Centro Fermi (Rome, Italy). CGWK receives funding from Horizon2020 (#945539), BRC (#BRC704/CAP/CGW), MRC (#MR/S026088/1), Ataxia UK, MS Society (#77), Wings for Life (#169111). CGWK is a shareholder in Queen Square Analytics Ltd.

References

1. Premack D, Woodruff G. Does the chimpanzee have a theory of mind? Behav Brain Sci. 1978;4:515-526.

2. Rizzolatti G, Fadiga L, Fogassi L, Gallese V. Resonance behaviors and mirror neurons. Arch Ital Biol. 1999;137:85-100.

3. Casiraghi L, Alahmadi AAS, Monteverdi A, et al. I See Your Effort: Force-Related BOLD Effects in an Extended Action Execution–Observation Network Involving the Cerebellum. Cereb Cortex. Published online 2019:1-18. doi:10.1093/cercor/bhy322

4. Alahmadi AAS, Pardini M, Samson RS, et al. Cerebellar lobules and dentate nuclei mirror cortical force-related-BOLD responses: Beyond all (linear) expectations. Hum Brain Mapp. 2017;38(5):2566-2579. doi:10.1002/hbm.23541

5. Alahmadi AAS, Samson RS, Gasston D, et al. Complex motor task associated with non-linear BOLD responses in cerebro-cortical areas and cerebellum. Brain Struct Funct. 2016;221(5):2443-2458. doi:10.1007/s00429-015-1048-1

6. Tzourio-Mazoyer N, Landeau B, Papathanassiou D, et al. Automated anatomical labeling of activations in SPM using a macroscopic anatomical parcellation of the MNI MRI single-subject brain. Neuroimage. 2002;15(1):273-289. doi:10.1006/nimg.2001.0978

7. Diedrichsen J, Balsters JH, Flavell J, Cussans E, Ramnani N. A probabilistic MR atlas of the human cerebellum. Neuroimage. 2009;46(1):39-46. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.01.045

8. Smith RE, Tournier JD, Calamante F, Connelly A. Anatomically-constrained tractography: improved diffusion MRI streamlines tractography through effective use of anatomical information. Neuroimage. 2012;62(3):1924-1938. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.06.005

9. Rubinov M, Sporns O. Complex network measures of brain connectivity: uses and interpretations. Neuroimage. 2010;52(3):1059-1069. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.10.003

10. Zalesky A, Fornito A, Bullmore ET. Network-based statistic: identifying differences in brain networks. Neuroimage. 2010;53(4):1197-1207. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.06.041

Figures