3494

Acute Effects of Psilocybin and Salvinorin-A on Functional Connectivity1Radiology, Athinoula A. Martinos Center for Biomedical Imaging, Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Charlestown, MA, United States, 2Neurobiology Research Unit, Institute of Clinical Medicine, University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen, Netherlands

Synopsis

Keywords: Brain Connectivity, fMRI (resting state)

This work utilized fMRI to assess the influence of the psychedelics, Psilocybin, a serotonergic agonist, and Salvinorin-A, a kappa-opioid receptor (KOR) agonist, on functional connectivity (FC) in non-human primates. We used a seed-based FC analysis, probing regions of interest associated with psychedelic hallucinogens. Our findings highlight the overlapping and differing influence of these substances on FC relative to the subcomponents of the default mode network and the claustrum. This work may provide insight on the mechanisms of action of psychedelics that target differing receptor systems.

Key Words: Functional connectivity; Claustrum; DMN; Psychedelics.

Introduction

Classical psychedelic substances like psilocybin act as agonists to the serotonin 2A receptor (5-HT2AR) and have received enormous attention for positive effects on disorders such as depression1 and alcoholism.2 In contrast, Salvinorin-A is a non-euphoric kappa opioid receptor (KOR) agonist which may elicit positive outcomes for addiction and anti-nociception3 with similar behavioral, dissociative, and hallucinogenic characteristics to classic psychedelics.4 Modulations of default mode network (DMN) functional connectivity (FC) is widely suggested for serotonergic psychedelics.5–7 Of the one fMRI study on Salvinorin-A, desynchronization was identified in the DMN.8 Beyond the DMN, recent evidence points to the claustrum as a key mediator for regulating cognitive disorders9–11 and possibly psychedelic effects.12 This work evaluates the effects of Psilocybin and Salvinorin-A on FC to elucidate similarities and/or differences between serotonergic and non-serotonergic psychedelics concerning DMN regions and the claustrum.Methods

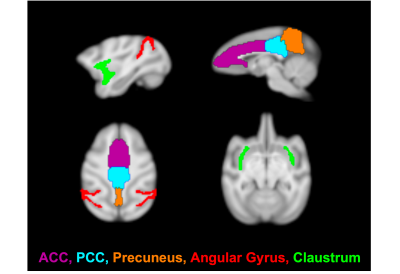

Imaging was performed on a 3T Siemens TIM-Trio with a BrainPET insert with two custom 8-channel head coils (one designed for larger NHP, the other for smaller NHP). Each NHP was anesthetized and maintained at ~1.0-1.2% isofluorane. A 1mm isotropic T1-weighted MPRAGE (TE1/TE2/TE3/TE4 = 1.64/3.5/5.36/7.22 ms, TR = 2530 ms, TI = 1200 ms, flip angle = 7°) was acquired as an anatomical image. For fMRI, NHP were injected with Ferumoxytol (MION; 10mg/kg) to improve SNR. An EPI sequence (TE/TR = 22/3000ms, 1.3mm isotropic resolution) was acquired for approximately 100 minutes (~2000 repetitions). NHP received an intravenous solution of either Psilocybin (30μg/kg, N=2; 60μg/kg, N=3; 90μg/kg, N=2) or Salvinorin-A (2μg/kg, N=2; 4μg/kg, N=4) after sufficient pre-drug functional data had been acquired (~20-60 min after scan initiation).Data preprocessing included slice-timing correction, motion-correction, brain extraction, registration to a common space NHP template, bias-field correction, 4mm spatial smoothing, extraction of 15-min of resting state data before and after drug-injection, grand-mean scaling, band-pass filtering (0.005-0.1 Hz), linear and quadratic trend removal, and nuisance regression of motion, CSF and white matter parameters. Seed-based analysis was performed (Figure 1) with ROI of DMN subcomponents of anterior and posterior cingulate cortices (ACC/PCC), precuneus and angular gyrus. The claustrum was also included to test the cortico-claustro-cortical model.12 Pearson’s correlation coefficients were calculated for extracted signals with respect to each seed vs each voxel in the brain and then converted to Z-scores. Statistical analysis was performed with a paired t-test of pre-drug vs. post-drug data, significance level set to 0.05, correction for cluster size and multiple comparisons, and Z-score thresholding of 2.3.

Results

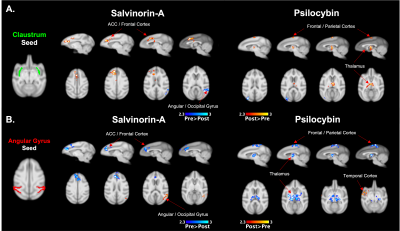

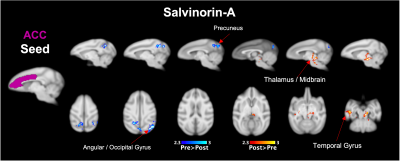

Both Salvinorin-A and Psilocybin increased FC from the claustrum to areas of the frontal cortex, but Psilocybin also increased FC to the thalamus (Fig. 2a). Dissociation was observed for both drugs from the angular gyrus seed region (Fig. 2b) to cortical regions. Psilocybin also had a strong dissociation from angular gyrus to thalamic regions. Salvinorin-A showed ACC dissociation from the precuneus and angular gyrus and slightly increased FC to thalamic regions (Fig. 3), while Psilocybin did not show any ACC seed modulations. Minor changes were also seen in temporal and motor cortices for both drugs in separate instances but were only observed in one hemisphere (Fig. 2b, 3). No FC changes were observed from PCC or precuneus seeds.Discussion

Overlapping changes induced by Salvinorin-A and Psilocybin were (1) increased FC from the claustrum to cortical regions (anterior for Salvinorin-A, posterior/parietal for Psilocybin), and (2) dissociation from the angular gyrus to those same regions. This gives additional credence to the cortico-claustro-cortical model12 while supporting previous findings of DMN-based dissociations due to these psychedelics.7,8 Additionally, an inverse relationship between the claustrum and angular gyrus seed regions (increased FC from claustrum to a region = reduced angular gyrus FC to the same area; see cortical and thalamic regions in Fig. 2) observed for both drugs supports a synergistic relationship between the two seeds not identified previously. These specific modulations could provide an over-arching framework to understand broader mechanisms at which psychedelics act regardless of target receptor.Salvinorin-A was unique in that cortical modulations were the primary effect, whereas Psilocybin had strongest FC changes relative to the thalamus – much more so than Salvinorin-A. DMN dissociation was also more widespread for Salvinorin-A, as FC reduced from ACC seed to the precuneus and angular gyrus. This may indicate the thalamus, in addition to relative DMN dissociation, as a primary target for differences between serotonergic and non-serotonergic psychedelics. Mechanistic similarities and differentiations identified between these substances may help define their utility for applications to medical conditions concerning the implicated networks (addiction, depression, etc.).

Conclusions

This work performed a direct comparison between Salvinorin-A and Psilocybin. Both drugs increased connectivity from claustrum to cortical regions, while Psilocybin alone influenced thalamic areas. Dissociation was most prominent with respect to the angular gyrus for both drugs, while only Psilocybin also reduced FC to thalamic regions. This implicates a claustrum / angular gyrus paradigm for psychedelic activity irrespective of serotonergic potential and highlights additional modulatory effects independently unique to Salvinorin-A and Psilocybin. Follow up analysis will investigate additional cortical and sub-cortical seed regions to further elucidate the mechanisms of these psychedelic drugs will be performed.Acknowledgements

Project Funding from Atai Life Sciences supported the Salvinorin-A work. BBRF Young Investigator grant and Lundbeck Foundation (R293-2018-738) supported the Psilocybin work. Additional Pilot Funding from the Athinoula A. Martinos Center for Biomedical Imaging, Department of Radiology, Massachusetts General Hospital.References

1. Griffiths, R. R. et al. Psilocybin produces substantial and sustained decreases in depression and anxiety in patients with life-threatening cancer: A randomized double-blind trial. J Psychopharmacol 30, 1181–1197 (2016).

2. Krebs, T. S. & Johansen, P. Ør. Lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) for alcoholism: Meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Journal of Psychopharmacology 26, 994–1002 (2012).

3. Cruz, A., Domingos, S., Gallardo, E. & Martinho, A. A unique natural selective kappa-opioid receptor agonist, salvinorin A, and its roles in human therapeutics. Phytochemistry 137, 9–14 (2017).

4. Maqueda, A. E. et al. Salvinorin-A Induces Intense Dissociative Effects, Blocking External Sensory Perception and Modulating Interoception and Sense of Body Ownership in Humans. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 18, 1–14 (2015).

5. Carhart-Harris, R. L. et al. Functional connectivity measures after psilocybin inform a novel hypothesis of early psychosis. Schizophr Bull 39, 1343–1351 (2013).

6. Daws, R. E. et al. Increased global integration in the brain after psilocybin therapy for depression. Nat Med 28, 844–851 (2022).

7. Madsen, M. K. et al. Psilocybin-induced changes in brain network integrity and segregation correlate with plasma psilocin level and psychedelic experience. European Neuropsychopharmacology 50, 121–132 (2021).

8. Doss, M. K. et al. The Acute Effects of the Atypical Dissociative Hallucinogen Salvinorin A on Functional Connectivity in the Human Brain. Scientific Reports 2020 10:1 10, 16392 (2020).

9. Barrett, F. S., Krimmel, S. R., Griffiths, R., Seminowicz, D. A. & Mathur, B. N. Psilocybin acutely alters the functional connectivity of the claustrum with brain networks that support perception, memory, and attention. Neuroimage 218, 116980 (2020).

10. Nikolenko, V. N. et al. The mystery of claustral neural circuits and recent updates on its role in neurodegenerative pathology. Behavioral and Brain Functions 17, 8 (2021).

11. Niu, M. et al. Claustrum mediates bidirectional and reversible control of stress-induced anxiety responses. Sci Adv 8, 6375 (2022).

12. Doss, M. K. et al. Models of psychedelic drug action: Modulation of cortical-subcortical circuits. Brain 145, 441–456 (2022).

Figures