3491

Functional connectivity density changes in adolescent contact and non-contact sport athletes1Radiology, Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, WI, United States, 2Neurosurgery, Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, WI, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Brain Connectivity, Traumatic brain injury, Functional connectivity density

Repetitive head impact exposure (RHIE) during contact sports (CS) might have potentially long-term neurological effects. We evaluated the effect of sport, time, and their interaction on local and global functional connectivity density (FCD) as measured using an advanced multiband multi-echo EPI sequence in CS and non-contact sport (NCS) middle school and high school athletes. Significant effects of sport and the interaction between sport and time on both local and global FCD were detected, which might suggest functional connections alterations due to contact sport participation.

Introduction

There is growing concern that repetitive head impact exposure (RHIE) while playing contact sports (CS) may lead to a variety of worrisome outcomes, including neurobehavioral problems and long-term cognitive deficits1-3, although the underlying mechanisms remain unknown. Existing related studies have focused on college-aged athletes. Resting-state fMRI has been applied to investigate brain networks in relation to RHIE in CS athletes3-5; however, these approaches generally require an apriori seed selection or the selection of a brain network of interest. In contrast, the present study used the data-driven functional connectivity density (FCD) method. We evaluated the effect of sport, time, and their interaction in contact sport (CS) and non-contact sport (NCS) middle school and high school athletes using an advanced multiband, multi-echo (MBME) MRI sequence.Methods

Fifty-nine male, non-concussed, United States middle school and high school CS (N=37) and NCS (N=22) athletes underwent MRI scans before and after their respective seasons. Overall, 32 CS and 15 NCS athletes completed the follow-up scan at postseason of Year 1.Imaging was performed on a 3T GE scanner. A T1-weighted MPRAGE anatomical image was acquired, followed by a gradient echo multiband, multi-echo (MBME) resting state fMRI (rs-fMRI) scan with the following parameters: TR/TE=900/11,30,49ms, FOV=24cm, matrix=80x80, slice thickness=3mm 11 slices with multiband factor=4 (44 total slices), FA=60°, partial Fourier factor=0.85, and in-plane acceleration (R)=2. Resting state scans lasted 7:28. During the resting state scans, subjects were instructed to close their eyes, but remain awake. A short, reversed polarity MBME scan was also collected to allow for image distortion correction.

Data was analyzed using a combination of AFNI and FSL. First, the anatomical MPRAGE image was coregistered to Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) space. Then, the first-echo functional data was volume registered to the first volume. Subsequent echoes were registered using the transformation matrices from the first echo. Image distortion was corrected using topup. The three echoes were then combined using the -weighted approach6 and denoised using multi-echo independent component analysis (ME-ICA)7-9 by regressing non-BOLD independent components out of the combined ME data. The denoised MBME dataset was then registered to the MPRAGE image and registered to MNI space using the anatomical transformations computed above. Finally, the data was smoothed with a 6mm FWHM Gaussian kernel and bandpass filtered with 0.01<f<0.08Hz.

Both local and global FCD were computed using methods based on previous work10-16 and 3dLFCD and 3dDegreeCentrality respectively in AFNI. The number of voxels connected to a specific voxel (v0) was determined using Pearson correlation and a correlation threshold of R ≥ 0.6. lFCD was defined as the number of voxels functionally connected to a voxel or to the voxels that are functionally connected to the local cluster of that voxel. This procedure was repeated for every voxel in the brain. gFCD was computed by counting the number of voxels functionally connected to a voxel throughout the whole brain and also repeated for every voxel in the brain.

Linear mixed-effects models were fit using 3dLMEr in AFNI to test the effects of time (pre- to post-season difference), contact group (CS vs. NCS), and group-by-time interactions in lFCD and gFCD. Age, BMI, and concussion history were included as covariates. Post-hoc general linear tests were performed to compare across time for each group individually and across groups at each time. Multiple comparisons were controlled for using a cluster size correction technique and 3dClustSim in AFNI (p < 0.05, α < 0.05).

Results

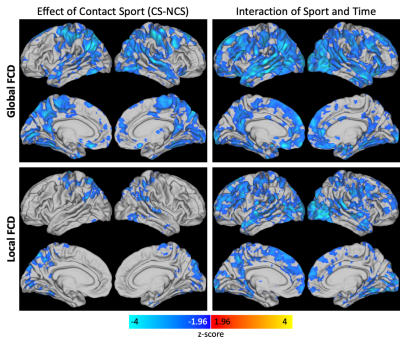

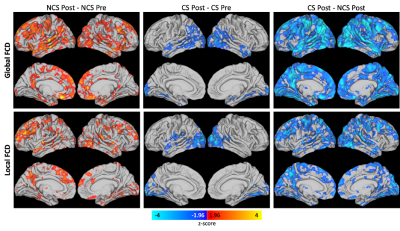

Results were similar for the lFCD and gFCD metrics. For both lFCD and gFCD there was a significant effect of contact group and a significant interaction effect between contact group and time (Figure 1). Post-hoc analyses (Figure 2) revealed a significant increase in lFCD and gFCD from post- to pre-season in the NCS group. A significant decrease in lFCD and gFCD was seen from post- to pre-season in the CS group in the visual cortex and temporal lobe. A global decrease in lFCD and gFCD was observed between CS and NCS groups.Discussion/Conclusions

Using the data driven FCD method, we observed a negative association between FCD and contact sport participation. Interestingly, FCD significantly increased in NCS athletes across one season suggesting a potential seasonal effect. Our findings are in line with previous functional connectivity research on RHIE, where default mode network connectivity was found to be lower in CS athletes vs. NCS athletes and NCS athletes saw increased connectivity over the course of one season5. Our results suggest both short-range and long-range connections may be altered by sport participation. Additional research is needed to further reveal the clinical implications of these results.Acknowledgements

No acknowledgement found.References

1. Stern RA, Riley DO, Daneshvar DH, Nowinski CJ, Cantu RC, McKee AC. Long-term consequences of repetitive brain trauma: chronic traumatic encephalopathy. PM & R : the journal of injury, function, and rehabilitation 2011;3(10 Suppl 2):S460-467.

2. Roby PR, Duquette P, Kerr ZY, Register-Mihalik J, Stoner L, Mihalik JP. Repetitive Head Impact Exposure and Cerebrovascular Function in Adolescent Athletes. Journal of neurotrauma 2021;38(7):837-847.

3. Slobounov SM, Walter A, Breiter HC, Zhu DC, Bai X, Bream T, Seidenberg P, Mao X, Johnson B, Talavage TM. The effect of repetitive subconcussive collisions on brain integrity in collegiate football players over a single football season: A multi-modal neuroimaging study. Neuroimage Clin 2017;14:708-718.

4. Abbas K, Shenk TE, Poole VN, Breedlove EL, Leverenz LJ, Nauman EA, Talavage TM, Robinson ME. Alteration of default mode network in high school football athletes due to repetitive subconcussive mild traumatic brain injury: a resting-state functional magnetic resonance imaging study. Brain connectivity 2015;5(2):91-101.

5. DeSimone JC, Davenport EM, Urban J, Xi Y, Holcomb JM, Kelley ME, Whitlow CT, Powers AK, Stitzel JD, Maldjian JA. Mapping default mode connectivity alterations following a single season of subconcussive impact exposure in youth football. Human brain mapping 2021;42(8):2529-2545.

6. Posse S, Wiese S, Gembris D, Mathiak K, Kessler C, Grosse-Ruyken ML, Elghahwagi B, Richards T, Dager SR, Kiselev VG. Enhancement of BOLD-contrast sensitivity by single-shot multi-echo functional MR imaging. Magnetic resonance in medicine : official journal of the Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine / Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine 1999;42(1):87-97.

7. Kundu P, Brenowitz ND, Voon V, Worbe Y, Vertes PE, Inati SJ, Saad ZS, Bandettini PA, Bullmore ET. Integrated strategy for improving functional connectivity mapping using multiecho fMRI. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2013;110(40):16187-16192.

8. Kundu P, Inati SJ, Evans JW, Luh WM, Bandettini PA. Differentiating BOLD and non-BOLD signals in fMRI time series using multi-echo EPI. NeuroImage 2012;60(3):1759-1770.

9. DuPre E, Salo T, Markello R, Kundu P, Whitaker K, Handwerker D. ME-ICA/tedana: 0.0.6: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.2558498. 2019.

10. Tomasi D, Volkow ND. Functional connectivity density mapping. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2010;107(21):9885-9890.

11. Tomasi D, Volkow ND. Functional connectivity hubs in the human brain. NeuroImage 2011;57(3):908-917.

12. Tomasi D, Volkow ND. Association between functional connectivity hubs and brain networks. Cerebral cortex 2011;21(9):2003-2013.

13. Tomasi D, Volkow ND. Gender differences in brain functional connectivity density. Human brain mapping 2012;33(4):849-860.

14. Tomasi D, Volkow ND. Abnormal functional connectivity in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Biol Psychiatry 2012;71(5):443-450.

15. Tomasi D, Shokri-Kojori E, Volkow ND. Temporal Evolution of Brain Functional Connectivity Metrics: Could 7 Min of Rest be Enough? Cereb Cortex 2016.

16. Cohen AD, Tomasi D, Shokri-Kojori E, Nencka AS, Wang Y. Functional connectivity density mapping: comparing multiband and conventional EPI protocols. Brain Imaging Behav 2018;12(3):848-859.

Figures

Figure 1. Overall effect of contact sport and the interaction of sport and time for global (top) and local (bottom) FCD.

Figure 2. Post hoc general linear tests for global (top) and local (bottom) FCD. NCS participants saw an increase in FCD while CS participants saw a decrease in FCD over the course of one season. Compared to NCS participants, FCD was lower for CS participants at the post season scan.