3489

Seasonal variations of functional connectivity of human brains1Vanderbilt University Institute of Imaging Science, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, TN, United States, 2Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN, United States, 3Department of Radiology and Radiological Sciences, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, TN, United States, 4Department of Biomedical Engineering, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN, United States, 5Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, TN, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Brain Connectivity, Brain Connectivity, Seasonality

Seasonal variations have been observed in various aspects of human behavior. While studies have explored the seasonality effects in cognition and mood, possible underlying seasonal variations of human brain activity have not gained wide attention. Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) based on blood-oxygenation-level-dependent (BOLD) effects can detect and map functional activity and thus provides opportunities to characterize seasonal variations in brain functions. This work used fMRI data from the Human Connectome Project (HCP) to quantify seasonal patterns of brain connectivity. Knowledge of seasonality effects in brain activity offers the potential of advancing our understanding of seasonal variations in human behavior.Introduction

It has been long recognized that the mood, cognition, and behavior of human beings exhibit seasonal variations1, a natural phenomenon that can be noted in a substantial portion of the general population2. To understand the underlying mechanism of seasonality effects, a large body of literature has examined seasonal variations of hormone level3,4, neural transmitter activities5-8 and gene expression profiles9,10. Furthermore, previous investigators have also characterized the seasonal variations of mood, cognition and behavioral or physiological variables11-16. Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) studies of the human brain have been attempted using resting state or specifically designed task paradigms, which demonstrated variations of brain activities over the time scale of months to years17-21. Still, while we can point to many examples of the seasonality effects on the brain, the seasonal variations of underlying brain activities still remain largely elusive.Previous research has pointed out that BOLD signals in white matter (WM) may contain important spatiotemporal information22-24. Synchronous neural activity between GM regions and WM bundles can be seen in functional connectivity (FC) matrices and the overall global average of GM-WM connectivity can characterize the synchronization of functional brain activities25. Given the previous evidence showing biophysical and cognitive variations across seasons, we hypothesized that we would be able to observe large-scale differential seasonal patterns in brain connectivity captured by fMRI in typical adults. In this work, we used data from healthy human subjects within the Human Connectome Project (HCP) and characterized the seasonal variations of group-averaged brain functional connectivity between parcellated gray matter (GM) regions and WM bundles, the fractional amplitude of low frequency fluctuations (fALFF) of regional functional signals, and the topological properties of the brain functional networks. In the present study, we further explored how environmental factors, including average temperature and daylength, affect seasonality of resting-fMRI based brain connectivity.

Methods

410 healthy young adults (60% female, age range = 26-35) were selected from the HCP S1200 3T MR database. The data acquisition seasons provided by HCP are defined as follows: Spring is from February 1st to April 30th; Summer is from May 1st to July 31st; Autumn is from August 1st to October 31st; and Winter is from November 1st to January 31st26. In addition to minimal preprocessing from HCP27, further processing included regressing-out of nuisance variables from head movements, cardiac signals and respiratory signals using the PhysIO toolbox28. Finally, time courses were bandpass filtered to retain the frequency from 0.01 to 0.1 Hz, and then normalized to unit variance voxel-wise. 90 ROIs of GM were defined using the atlas from W. R. Shirer, et. al.29, and WM was parcellated into 48 fiber bundles using the JHU ICBM-DTI-81 WM atlas30. The fMRI BOLD signals were averaged across voxels in each GM region and WM bundle, yielding region-averaged signals for the calculation of each FC matrix and fALFF and subsequent seasonal variation analyses. Sinusoidal functions were used as regressors to determine whether there were significant seasonal variations in brain activity captured by FC between GM regions and WM bundles, low-frequency fluctuations in WM fMRI signals, and topological properties of functional brain networks. Seasonal variations of environmental factors including average temperature and daylength were also examined and correlated with the brain activity measures. Statistical inferences were made using F-tests to determine the significance of seasonal periodicity.Results

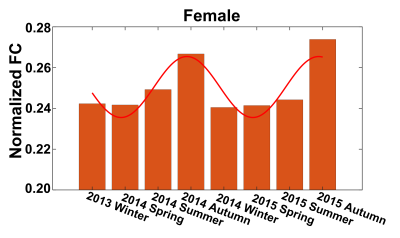

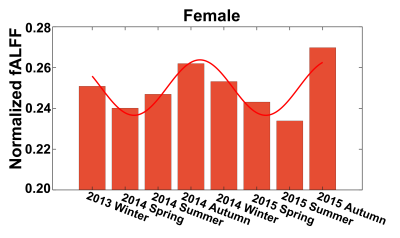

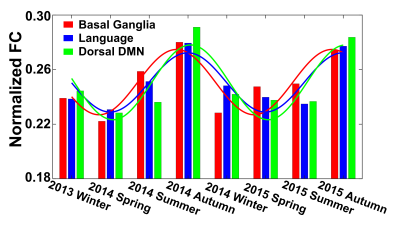

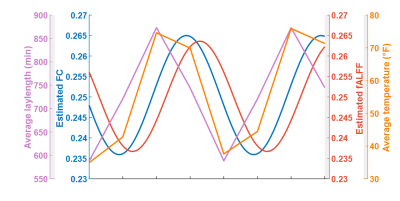

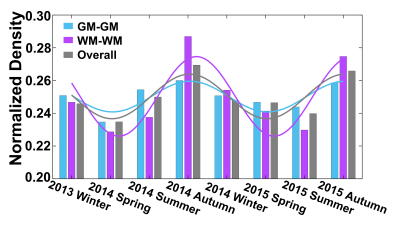

Seasonal variations of FC strength (Figure 1) and the fractional amplitude of low-frequency fluctuations (fALFF) of WM bundles (Figure 2) were observed in the female group at global-level (p<0.05) where FC and fALFF reached their peaks in autumn, whereas periodic seasonal variations were not significant in the male group. Statistically significant differences were also found between two seasons that have maximum and minimum group-averaged value for FC and fALFF in the female group (p<0.05). Further analysis demonstrated that the FC strength of several functional networks, especially the basal ganglia network, showed a seasonal periodicity (p=0.0304) (Figure 3). The average temperature and daylength were found to be significantly associated with the functional metrics of the female group (p<0.05) (Figure 4). Additionally, topological properties of the brain functional network also exhibited significant variations across seasons (Figure 5).Discussion

Seasonal variations of functional activities were observed in the female group at both global- and network-levels. All the observations demonstrate seasonality effects on human brain activity in a resting-state. The variation of the basal ganglia network showed strong overall seasonality effects. Previous findings of seasonal effects on striatal presynaptic dopamine synthesis agree with our observations31,32, which converges to suggest that the basal ganglia system might be one of the driving structures underlying the seasonal variations of brain activity. In addition to the mechanistic insight derived regarding the seasonality effects of human brain activity, from the practical perspective, findings from this work may also be used to guide fMRI-based research designs with environmental factors appropriately considered.Conclusion

This study demonstrated significant patterns of seasonal variations of brain activity measured by resting-state fMRI, thus improving our understanding of seasonality effects on functional networks in the human brain.Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant RF1 MH123201 (J.C.G), R01 NS113832 (J.C.G), T32 EB001628 (S.C.), and Vanderbilt Discovery Grant FF600670 (Y.G).References

1. L. Sher, “Seasonal Affective Disorder and Seasonality: A Review,” Jefferson Journal of Psychiatry, vol. 15, no. 1, 2000, doi: 10.29046/jjp.015.1.001.

2. C. Davis and R. D. Levitan, “Seasonality and seasonal affective disorder (SAD): An evolutionary viewpoint tied to energy conservation and reproductive cycles,” Journal of Affective Disorders, vol. 87, no. 1. pp. 3–10, Jul. 2005. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2005.03.006.

3. K. Honma, M. Kohsaka, N. Fukuda, and S. Honma, “Seasonal variation in the human circadian rhythm: dissociation between sleep and temperature rhythm,” 1992.

4. D. Vondrasova, I. Hajek, and H. Illnerova, “Exposure to long summer days affects the human melatonin and cortisol rhythms,” 1997.

5. D. P. Eisenberg, P. D. Kohn, E. B. Baller, J. A. Bronstein, J. C. Masdeu, and K. F. Berman, “Seasonal effects on human striatal presynaptic dopamine synthesis,” Journal of Neuroscience, vol. 30, no. 44, pp. 14691–14694, Nov. 2010, doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1953-10.2010.

6. B. Mc Mahon et al., “Seasonal difference in brain serotonin transporter binding predicts symptom severity in patients with seasonal affective disorder,” Brain, vol. 139, no. 5, pp. 1605–1614, May 2016, doi: 10.1093/brain/aww043.

7. N. Praschak-Rieder, M. Willeit, A. A. Wilson, S. Houle, and J. H. Meyer, “Seasonal Variation in Human Brain Serotonin Transporter Binding.”

8. S. Ray et al., “Seasonal plasticity in the adult somatosensory cortex,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, vol. 117, no. 50, p. 32136, Dec. 2020, doi: 10.1073/pnas.1922888117.

9. P. A. F. Madden, A. C. Heath, N. E. Rosenthal, and N. G. Martin, “Seasonal Changes in Mood and Behavior The Role of Genetic Factors.” [Online]. Available: https://jamanetwork.com/

10. X. C. Dopico et al., “Widespread seasonal gene expression reveals annual differences in human immunity and physiology,” Nat Commun, vol. 6, May 2015, doi: 10.1038/ncomms8000.

11. P. J. Brennan, G. Greenberg, W. E. Miall, and S. G. Thompson, “Seasonal variation in arterial blood pressure,” Br Med J, vol. 285, no. 6346, pp. 919–923, 1982, doi: 10.1136/bmj.285.6346.919.

12. D. J. Gordon et al., “PATHOPHYSIOLOGY AND NATURAL HISTORY HYPERLIPIDEMlA Seasonal cholesterol cycles: the Lipid Research Clinics Coronary Primary Prevention Trial placebo group.” [Online]. Available: http://ahajournals.org

13. J. M. de Castro, “Seasonal Rhythms of Human Nutrient Intake and Meal Pattern.”

14. T. Brennen, M. Martinussen, O. Hansen, O. Hjemdal, and : T Brennen, “Arctic Cognition: A Study of Cognitive Performance in Summer and Winter at 698N.”

15. A. M. J. van Ooijen, W. D. van Marken Lichtenbelt, A. A. van Steenhoven, and K. R. Westerterp, “Seasonal changes in metabolic and temperature responses to cold air in humans,” Physiol Behav, vol. 82, no. 2–3, pp. 545–553, Sep. 2004, doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2004.05.001.

16. C. Christodoulou et al., “Suicide and seasonality,” Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, vol. 125, no. 2. pp. 127–146, Feb. 2012. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2011.01750.x.

17. X. Di, M. Wolfer, S. Kühn, Z. Zhang, and B. B. Biswal, “Estimations of the weather effects on brain functions using functional MRI: a cautionary note 1”, doi: 10.1101/646695.

18. A. S. Choe et al., “Reproducibility and temporal structure in weekly resting-state fMRI over a period of 3.5 years,” PLoS One, vol. 10, no. 10, Oct. 2015, doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0140134.

19. R. A. Poldrack et al., “Long-term neural and physiological phenotyping of a single human,” Nat Commun, vol. 6, Dec. 2015, doi: 10.1038/ncomms9885.

20. E. Filevich et al., “Day2day: Investigating daily variability of magnetic resonance imaging measures over half a year,” BMC Neurosci, vol. 18, no. 1, Aug. 2017, doi: 10.1186/s12868-017-0383-y.

21. C. Meyer et al., “Seasonality in human cognitive brain responses,” Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, vol. 113, no. 11, pp. 3066–3071, Mar. 2016, doi: 10.1073/pnas.1518129113.

22. P. Wang et al., “The Organization of the Human Corpus Callosum Estimated by Intrinsic Functional Connectivity with White-Matter Functional Networks,” Cerebral Cortex, vol. 30, pp. 3313–3324, 2020, doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhz311.

23. H. Lu et al., “White Matter fMRI Activation Cannot Be Treated as a Nuisance Regressor: Overcoming a Historical Blind Spot,” 2019, doi: 10.3389/fnins.2019.01024.

24. J. R. Gawryluk, E. L. Mazerolle, R. C. N D, and T. J. Grabowski, “Does functional MRI detect activation in white matter? A review of emerging evidence, issues, and future directions,” 2014, doi: 10.3389/fnins.2014.00239.

25. Z. Ding et al., “Detection of synchronous brain activity in white matter tracts at rest and under functional loading,” Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, vol. 115, no. 3, pp. 595–600, Jan. 2018, doi: 10.1073/pnas.1711567115.

26. M. R. Hodge et al., “ConnectomeDB—Sharing human brain connectivity data,” Neuroimage, vol. 124, pp. 1102–1107, Jan. 2016, doi: 10.1016/J.NEUROIMAGE.2015.04.046.

27. M. F. Glasser et al., “The minimal preprocessing pipelines for the Human Connectome Project,” Neuroimage, vol. 80, pp. 105–124, Oct. 2013, doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.04.127.

28. L. Kasper et al., “The PhysIO Toolbox for Modeling Physiological Noise in fMRI Data,” J Neurosci Methods, vol. 276, pp. 56–72, Jan. 2017, doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2016.10.019.

29. W. R. Shirer, S. Ryali, E. Rykhlevskaia, V. Menon, and M. D. Greicius, “Decoding subject-driven cognitive states with whole-brain connectivity patterns,” Cerebral Cortex, vol. 22, no. 1, pp. 158–165, Jan. 2012, doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhr099.

30. S. Mori et al., “Stereotaxic white matter atlas based on diffusion tensor imaging in an ICBM template,” Neuroimage, vol. 40, no. 2, pp. 570–582, Apr. 2008, doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.12.035.

31. D. P. Eisenberg, P. D. Kohn, E. B. Baller, J. A. Bronstein, J. C. Masdeu, and K. F. Berman, “Seasonal effects on human striatal presynaptic dopamine synthesis,” Journal of Neuroscience, vol. 30, no. 44, pp. 14691–14694, Nov. 2010, doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1953-10.2010.

32. J. Myslivecek, “Two Players in the Field: Hierarchical Model of Interaction between the Dopamine and Acetylcholine Signaling Systems in the Striatum,” 2021, doi: 10.3390/biomedicines9010025.

Figures