3484

Toward a detailed subject-specific cerebrovascular model using Arterial Spin Labeling (ASL) Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI)1Auckland Bioengineering Institute, The University of Auckland, Auckland, New Zealand, 2Faculty of Medical and Health Sciences & Centre for Brain Research, The University of Auckland, Auckland, New Zealand, 3Mātai Medical Research Institute, Tairāwhiti-Gisborne, New Zealand

Synopsis

Keywords: Blood vessels, Modelling, Arterial Spin Labeling, ASL, cerebral perfusion, CBF, 4D flow, blood flow

Computed flows via haemodynamic models highly depend on peripheral resistances that affect the blood perfusion. To this end, finding a way to estimate these resistances is crucial for having a subject-specific model. Perfusion (CBF) maps produced by Arterial Spin Labeling (ASL)-MRI provide valuable information via which the model can be personalized. This new approach may be promising for providing blood flow measurements of the brain from ASL-CBF data in the absence of a full brain 4D flow sequence.INTRODUCTION

Peripheral resistance of cerebral arteries plays a vital role in maintaining blood flow into the brain tissue, which varies across different subjects. From the computational point of view, different approaches exist for estimating these parameters and thereby building subject-specific models, including various Kalman filtering schemes, e.g., ROUKF1, optimal controllers2, proportional controllers3, and optimization-based algorithms4. However, to the best of our knowledge, only one study addressed the redundancy problem related to the large number of terminal arteries5. Here, the Murray's law was used to distribute the resistances with respect to their radii. However, this method is inaccurate for small arteries6. To improve upon this approach, we employed a neuro-fuzzy control scheme along with ASL-CBF data, to find the optimal values of resistances, by controlling the pressure and blood flow of both the internal carotid and other major cerebral arteries. After calibration, 4D flow data was used to validate the model.METHODS

Imaging acquisitionFollowing ethical approval, one participant (female age 28 yrs) was scanned on a 3T MRI scanner (GE SIGNA Premier; General Electric, MI, USA) using an AIRTM 48-channel head coil.

Three whole brain scans were acquired, capturing:

- Cerebral perfusion (CBF): 7 delay eASL: 22cm FOV, 9s/11ms TR/TE, 1.1 x 1.1 x 4.5 mm resolution, 1s post-label delay, 4s label duration, 5:00 min scan time

- 4D blood flow: 3D cine PC-MRI: 21cm FOV, 20 cardiac phases, 1.2 isotropic resolution, 80 cm/s venc, 2:30 min scan time

- Vessel geometry (non-contrast MRA): 3D PC-MRI, InhanceSag, 23cm FOV, 40 cm/s venc, 0.8 mm isotropic resolution, 2:17 min scan time.

Post-processing

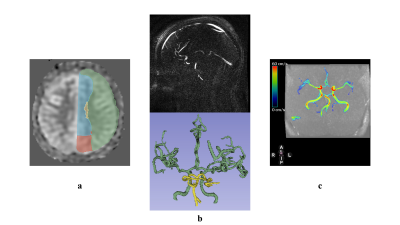

The CBF map based on ASL data was registered to MNI space, and next, by means of the atlas of brain territories (https://www.nitrc.org/projects/arterialatlas), perfusion maps of major cerebral arteries (ACA, MCA, PCA, and Basilar) were extracted (Fig. 1).

Hemodynamic model

Using the geometry extracted from the MRA sequence – namely vessel connections, their radii, and lengths – we created a detailed lumped model of cerebral arteries with similar formulation as in Safaei et al.7. The outputs of the model are flow and pressure traces of different arteries, which can be obtained via real-time simulations; this is fast and thus would be feasible clinically.

Model calibration

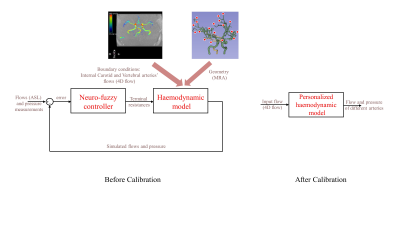

A challenge in modelling is the redundancy problem, that is, the number of unknowns (peripheral resistances) are larger than the knowns (measured flow and pressure). So here, we used the neuro-fuzzy control scheme8,9 to compute the peripheral resistances, to get the same values of flow and pressure as the ASL and pressure measurements (the latter which uses the mean pressure value from the literature). In fact, the controller learns to manipulate the terminal resistances efficiently, as control efforts, to track a desired pressure of a specified point in the arterial system with a penalty term on blood flow fractions, which is helpful in resolving redundancy in the cerebrovascular model (Fig. 2).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

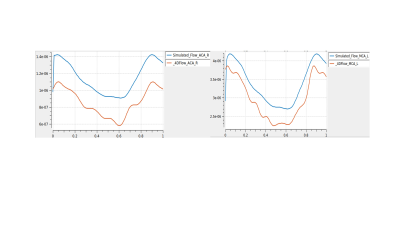

This work presents a novel approach to simulating brain blood flow measurements based on ASL-CBF data. This approach helps account for the dissipative effects of small arteries. The simulation results are qualitatively consistent with the flow measurements taken from different arteries found from 4D flow (Fig. 3). However, in general, the model overpredicts arterial flow with a relative error of 35 ± 8% (right ACA) and 15 ± 5% (left MCA). These errors are likely due to inaccuracies in (1) the detection of vascular geometry, (2) the CBF maps (since several assumptions are made in the ASL processing method), (3) the atlas used to find the CBF maps (which is based on a limited population size) and (4) other model parameters such as arterial wall thickness. Furthermore, processing 4D flow data presents numerous challenges since the sampling error may be quite high for small cerebral arteries. 4D flow also suffers from intrinsic errors, both in the acquisition and post-processing steps – the latter of which can be operator dependent.

Regarding the overprediction, we will scrutinize whether any dissipative effect has been neglected, resulting in a larger blood flow. Moreover, we are working on finding a reproducible way of segmenting small arteries from 4D flow data to enhance the reproducibility and robustness of the method. In terms of ASL processing, we need to find a more personalized atlas rather than a population-based affined-deformed atlas used in the current study.

CONCLUSION

This study showed that the blood flow of different cerebral arteries, estimated using ASL-CBF, qualitatively matches the characteristic blood flow curve of the acquired 4D flow data. This novel approach computed peripheral resistances of a lumped cerebrovascular model using ASL data and a neuro-fuzzy control scheme. A subgroup of the results of the model was compared with respective 4D flow measurements. While there is room for improvement of the modeling errors that give rise to an overprediction of the flow, this is a promising approach for providing blood flow measurements of the brain from ASL-CBF data without the need for an additional full brain 4D flow sequence.Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Aotearoa Foundation, the Royal Society of New Zealand Marsden Fund, and the Kānoa - Regional Economic Development & Investment Unit, New Zealand. We are grateful to Mātai Ngā Māngai Māori for their guidance and to our research participants for dedicating their time toward this study. We would like to acknowledge the support of GE Healthcare for assisting with the MRI acquisitions.References

1. A Caiazzo, F Caforio, G Montecinos, LO Muller, PJ Blanco, EF Toro. Assessment of reduced‐order unscented Kalman filter for parameter identification in 1‐dimensional blood flow models using experimental data. International journal for numerical methods in biomedical engineering. 33:e2843 (2017).

2. E Fevola, F Ballarin, L Jiménez‐Juan, S Fremes, S Grivet‐Talocia, G Rozza, P Triverio. An optimal control approach to determine resistance‐type boundary conditions from in‐vivo data for cardiovascular simulations. International Journal for Numerical Methods in Biomedical Engineering. 37:e3516 (2021).

3. J Schollenberger, NH Osborne, L Hernandez-Garcia, CA Figueroa. A combined computational fluid dynamics and arterial spin labeling MRI modeling strategy to quantify patient-specific cerebral hemodynamics in cerebrovascular occlusive disease. Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology. 9:722445 (2021).

4. P Perdikaris, GE Karniadakis. Model inversion via multi-fidelity Bayesian optimization: a new paradigm for parameter estimation in haemodynamics, and beyond. Journal of The Royal Society Interface. 13:20151107 (2016).

5. PJ Blanco, SM Watanabe, EA Dari, MARF Passos, RA Feijóo. Blood flow distribution in an anatomically detailed arterial network model: criteria and algorithms. Biomechanics and modeling in mechanobiology. 13:1303-1330 (2014).

6. TF Sherman. On connecting large vessels to small. The meaning of Murray's law. The Journal of general physiology. 78:431-453 (1981).

7. S Safaei, PJ Blanco, LO Müller, LR Hellevik, PJ Hunter. Bond graph model of cerebral circulation: toward clinically feasible systemic blood flow simulations. Frontiers in physiology. 9:148 (2018).

8. B Nasseroleslami, G Vossoughi, M Boroushaki, M Parnianpour. Simulation of movement in three-dimensional musculoskeletal human lumbar spine using directional encoding-based neurocontrollers. Journal of Biomechanical Engineering. 136:091010 (2014).

9. A Sharifzadeh-Kermani, N Arjmand, G Vossoughi, A Shirazi-Adl, AG Patwardhan, M Parnianpour, Kinda Khalaf. Estimation of Trunk Muscle Forces Using a Bio-Inspired Control Strategy Implemented in a Neuro-Osteo-Ligamentous Finite Element Model of the Lumbar Spine. Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology. 8:949 (2020).

Figures