3476

Super-resolution imaging on an MRI-linac to improve real-time MRI used in MRI guided radiation therapy.1Image X Institute, University of Sydney, Sydney, Australia, 2Ingham Institute for Applied Medical Research, Sydney, Australia

Synopsis

Keywords: Machine Learning/Artificial Intelligence, Machine Learning/Artificial Intelligence, MRI guided radiation therapy

Real-time MRI is limited in its spatiotemporal resolution due to imaging time being proportional to the spatial resolution. Super-resolution imaging was integrated into an MRI-linac to improve the spatiotemporal resolution of images used in real-time adaptive MRI guided radiation therapy. Real-time up-sampling techniques included conventional bicubic interpolation and deep learning-based super-resolution. Up-sampling increased the spatial resolution as characterised by healthy volunteer brain and thorax MRIs with negligible impact on the temporal resolution as measured in a motion phantom tracking experiment.

Introduction

Real-time adaptive MRI guided radiation therapy (MRIgRT) accounts for intrafraction physiological motion that degrades treatment accuracy. A limiting factor of real-time adaptive MRIgRT is the spatiotemporal resolution of cine-MRI used to adapt treatment. Super-resolution takes a high temporal, low spatial resolution MRI and up-samples this to a higher spatial resolution while retaining the high temporal resolution. In this work, we leverage the Gadgetron to integrate deep learning-based and conventional up-sampling techniques onto an MRI-linac, thereby increasing the spatiotemporal resolution of real-time adaptive MRIgRT1.Methods

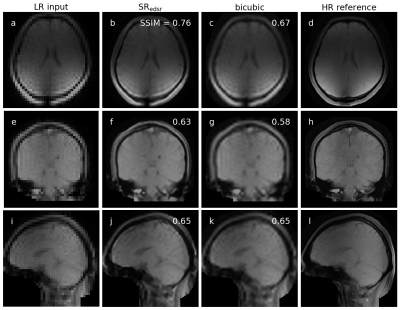

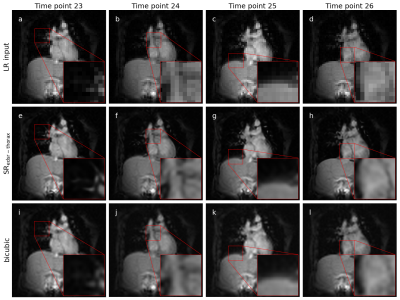

Two methods of up-sampling were selected for integration into the Australian MRI-linac: enhanced deep super-resolution (EDSR) network and bicubic interpolation (BI) as a conventional baseline2. Both of these techniques up-sampled a low spatial resolution input (matrix size = 64×64) to a high spatial resolution output (matrix size = 256×256). The deep learning-based EDSR was trained on brain MRIs from a brain cancer dataset (forming a ‘brain model’ – SRedsr) and fine-tuned to thorax MRIs from a lung cancer dataset (forming a ‘thorax model’ – SRedsr-thorax)3-7. These methods of up-sampling (SRedsr, SRedsr-thorax, and BI) were integrated onto the MRI-linac utilising Gadgetron, an open-source image reconstruction framework, and an in-house software. This integration included the sending of MRIs (with/without up-sampling) to a multi-leaf collimator (MLC) tracking software to enable enhanced real-time adaptive MRIgRT. The spatiotemporal resolution was characterised through offline and online experiments conducted on a prototype 1.0 T MRI-linac8.A qualitative and quantitative assessment was performed with orthogonal single-image brain imaging of a healthy volunteer. Due to minimal motion of the head between serial low and high spatial resolution acquisitions, up-sampled images (generated by the low spatial resolution images) could be directly compared to their high spatial resolution counterpart through a structural similarity (SSIM) and peak signal-to-noise ratio (PSNR). Free-breathing cine-MRI of a healthy volunteer’s thorax demonstrated the up-sampling techniques on the type of imaging used in real-time adaptive MRIgRT.

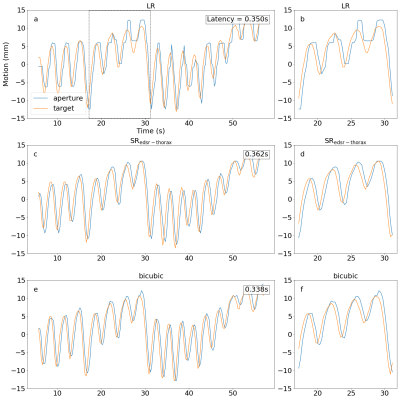

The temporal resolution was measured through a motion tracking experiment utilising a motion phantom capable of moving a target to sinusoid and patient breathing motion traces. In this experiment, the position (and consequently centroid) of the target and MLC aperture were determined using an electronic imaging portal detector (EPID) and template matching. The sinusoid motion trace quantified the end-to-end system latency by calculating the phase shift between fitted sinusoid curves of the target and MLC aperture. The root mean-square-error (RMSE) was calculated with/without latency correction for the patient breathing motion trace by measuring the distance between the target and MLC aperture centroids.

Results

Up-sampled brain MRIs were successfully produced from low spatial resolution input that were compared to a high spatial resolution reference (figure 1). Qualitatively, anatomical features were sharper in addition to a reduction in Gibb’s ringing artifacts when using SRedsr compared to BI. Quantitatively, the SSIM and PSNR increased when using SRedsr compared to BI (table 1). Cine thorax MRIs were reconstructed using SRedsr-thorax and BI methods (figure 2). Thoracic structures such as the heart and diaphragm were clearer for SRedsr-thorax and BI compared to their low spatial resolution input. SRedsr-thorax images qualitatively displayed sharper edges compared to BI images. The process of up-sampling (SRedsr, SRedsr-thorax, and BI) added negligibly to the imaging time using a NVIDIA RTX A5000 GPU at the MRI-linac. This was validated by the absence of a significant increase in the end-to-end system latency when using up-sampling techniques (table 2). The root mean-square-error (RMSE) did not change significantly when using real-time up-sampling; however, the latency-corrected RMSE reduced by around 40% (table 2). A plot of the target (when moving to a patient breathing trace) and aperture positions are presented in figure 3. We observed the difference in the end-to-end latency when using real-time up-sampling did not diminish tracking efficacy.Discussion

Super-resolution was successfully integrated into real-time adaptive MRIgRT using deep learning-based (SRedsr and SRedsr-thorax) and conventional (BI) techniques. The spatial resolution was increased utilising super-resolution as demonstrated in healthy volunteers on the MRI-linac system. Our integration of super-resolution had a comparable end-to-end system latency to a previous latency characterisation study on the same MRI-linac indicating a retention in the high temporal resolution afforded by conventional low spatial resolution imaging9. The uncertainty (previously measured to be in the order of 40 ms) of the end-to-end system latency is likely to account for the reduction when using BI compared to no super-resolution. The motion phantom has differences to actual intrafraction target motion present in radiotherapy such as out-of-plane motion, rotation, and deformations of the target while being situated in surrounded anatomy. This is an avenue of further investigation to establish the overall benefit of super-resolution imaging in the real-time adaptive MRIgRT workflow.Conclusion

Super-resolution imaging was integrated into an MRI-linac to increase the spatiotemporal resolution of MRIs used in real-time adaptive MRI guided radiation therapy. Super-resolution increased the spatial resolution of real-time MRIs with negligible increase to the temporal resolution as measured by volunteer and phantom experiments.Acknowledgements

David Waddington is supported by a Cancer Institute NSW Early Career Fellowship 2019/ECF1015. This work has been funded by the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council Program Grant APP1132471.

References

1. Hansen MS, Sørensen TS. Gadgetron: an open source framework for medical image reconstruction. Magnetic resonance in medicine. 2013;69(6):1768-1776.

2. Lim B, Son S, Kim H, Nah S, Mu Lee K. Enhanced deep residual networks for single image super-resolution. 2017:136-144.

3. Mamonov A, Kalpathy-Cramer J. Data From QIN GBM Treatment Response. The Cancer Imaging Archive. 2016;

4. Prah M, Stufflebeam S, Paulson E, et al. Repeatability of standardized and normalized relative CBV in patients with newly diagnosed glioblastoma. American Journal of Neuroradiology. 2015;36(9):1654-1661.

5. Clark K, Vendt B, Smith K, et al. The Cancer Imaging Archive (TCIA): maintaining and operating a public information repository. Journal of digital imaging. 2013;26(6):1045-1057.

6. Lee D, Greer PB, Lapuz C, et al. Audiovisual biofeedback guided breath-hold improves lung tumor position reproducibility and volume consistency. Advances in radiation oncology. 2017;2(3):354-362.

7. Lee D, Greer PB, Paganelli C, Ludbrook JJ, Kim T, Keall P. Audiovisual biofeedback improves the correlation between internal/external surrogate motion and lung tumor motion. Medical physics. 2018;45(3):1009-1017.

8. Keall PJ, Barton M, Crozier S. The Australian magnetic resonance imaging–linac program. Elsevier; 2014:203-206.

9. Liu PZ, Dong B, Nguyen DT, et al. First experimental investigation of simultaneously tracking two independently moving targets on an MRI‐linac using real‐time MRI and MLC tracking. Medical Physics. 2020;47(12):6440-6449.

Figures