3444

3D Seiffert spirals for efficient k-space sampling in 23Na-MRI: initial phantom simulations1NMR Research Unit, Queen Square MS Centre, Department of Neuroinflammation, UCL Queen Square Institute of Neurology, Faculty of Brain Sciences, University College London, London, United Kingdom, 2Department of Medical Physics and Biomedical Engineering, University College London, London, United Kingdom, 3Philips Healthcare, Best, Netherlands, 4Quantitative Imaging Group, Department of Medical Physics and Biomedical Engineering, University College London, London, United Kingdom, 5Department of Brain & Behavioural Sciences, University of Pavia, Pavia, Italy, 6Brain Connectivity Centre Research Department, IRCCS Mondino Foundation, Pavia, Italy

Synopsis

Keywords: New Trajectories & Spatial Encoding Methods, Non-Proton

Modern sodium MRI (23Na-MRI) uses efficient, non-Cartesian k-space sampling strategies to acquire 3D volumes in clinically feasible scan times. 3D Seiffert spirals are a novel k-space sampling scheme with improved efficiency to existing methods. 23Na-MRI, and particularly temporally resolved functional 23Na-MRI, could be an ideal application for Seiffert spirals. We present initial, in silico simulations of 3D Seiffert spiral k-space sampling for a highly undersampled 1.8 second functional 23Na-MRI protocol. Seiffert spirals generate images of improved quality and SNR in direct comparison to 3D-cones. Essential further work will involve compressed sensing reconstruction, further trajectory optimisation and in vivo imaging.

Introduction

Sodium magnetic resonance imaging (23Na-MRI) is a promising imaging modality providing novel insight into physiology and metabolism in vivo1,2. 23Na-MRI has become more widely implemented on clinical systems, stimulating novel applications, such as functional 23Na-MRI to study neuronal activity3,4. This requires the fastest possible ways of sampling k-space to maximise temporal resolution and become sensitive to slow 23Na dynamics5.23Na ions are quadrupolar, with a short bi-exponential T2 in tissue6 (T2s≈1-5ms, T2l≈20-40ms)7. Thus, modern 23Na-MRI uses non-Cartesian k-space readouts that sample the free induction decay (FID) directly after RF excitation8. Popular encoding schemes include 3D-radial9,10, FLORET11, TPI12 and 3D-cones13,14. Although the latter three are more efficient than radial sampling, the degree of k-space coverage per readout is still limited due to the spatial constraint to conical surfaces. This is also sub-optimal for grater undersampling, with compressed sensing reconstruction15, as coherent artifacts begin to surface. Recently, Speidel et al.16 demonstrated k-space sampling with 3D spherical Seiffert spirals for 1H MRI, reporting increased sampling efficiency and more incoherent undersampling artifacts than 3D-cones. Seiffert spiral sampling has also been implemented in 1H MR-fingerprinting17 and hyperpolarised 13C MRI18.

We postulate that a highly efficient, three-dimensional sampling approach like Seiffert spirals could make a tangible improvement to efficiency of 23Na-MRI acquisition. We plan to leverage this in formulating a functional 23Na MRI protocol, with temporal resolution of the order of 1s, and present results from initial in silico phantom simulations, as a first step towards in vivo experiments.

Theory

Seiffert spirals are spiral paths of (theoretically) infinite length that traverse the surface of the unit sphere at constant angular and linear velocity, passing through alternating poles16,19. They are parametrised in cylindrical coordinates by Jacobi’s elliptic functions $$$\mathrm{sn},\mathrm{cn}$$$19:$$\phi=\sqrt{m}s,\rho=\mathrm{sn}\left(s|m\right),z=\mathrm{cn}\left(s|m\right),$$

where $$$s$$$ is the total distance covered from the north pole $$$\left(\phi=\rho=0,z=1\right)$$$ and $$$0<m<1$$$ controls the spiral’s twist. Seiffert spirals can be converted into a centre-out k-space trajectory by16:

- defining a finite spiral length $$$s_t$$$;

- multiplying each point by a scaling function, $$$f_s$$$, $$$0{\leq}f_s{\leq}k_{max}$$$;

- rotating the spiral to fill k-space.

Methods

Trajectory designThe spiral length $$$s_t$$$ was approximately maximised for a given readout duration, resolution and sampling rate, so that a time-mininmal gradient waveform within hardware constraints19 existed. To choose $$$m$$$, an analytical expression was utilised that ensures an even azimuthal distribution of passes through the north pole:

$$m=\frac{\pi^2}{s^2_t}.$$

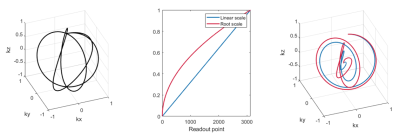

Linear and square-root scaling functions were considered, as the latter may yield SNR-favourable sampling densities9,21,22. The trajectory was rotated to end in an evenly distributed Fibonacci point lattice on the k-space sphere16.

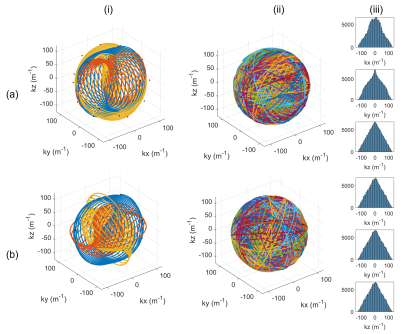

A novel strategy to encourage low 3D point discrepancy16 (high uniformity) involved repeating readouts three times, cycling through gradient axes with the scheme $$$[x,y,z]\rightarrow[z,x,y]\rightarrow[y,z,x]$$$. Keeping the total number of readouts constant, the number of Fibonacci endpoints was reduced by a factor of 3.

Protocols

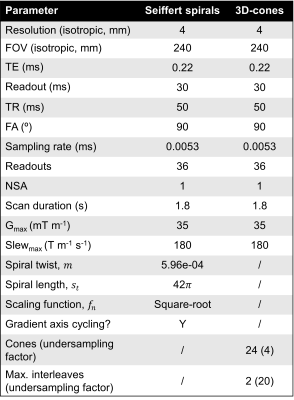

Table 1 shows a table of parameters for the Seiffert spiral and 3D-cones protocols simulated, each of duration=1.8s.

Simulations

Experiments involved forward and inverse non-uniform Fourier transforms23 with sampling density compensation24, to simulate point spread functions (PSFs) and a 3D Shepp-Logan phantom, in MATLAB (Naticks, Massachusetts). For more realistic results:

- Complex additive Gaussian white noise of SNR=6 was added in k-space.

- T2* relaxation was simulated using a bi-exponential signal model with T*2s=3ms, T*2l=20ms: $$S=0.6\exp\left(-\frac{t}{T^{\ast}_{2s}}\right)+0.4\exp\left(-\frac{t}{T^{\ast}_{2l}}\right).$$

- Incomplete T1 recovery was simulated by multiplying $$$S$$$ above with the following factor25, with flip angle $$$\alpha$$$ and T1=25ms: $$\beta = \sin\alpha\frac{1-\exp\left(-\frac{TR}{T_1}\right)}{1-\cos\alpha\exp\left(-\frac{TR}{T_1}\right)}.$$

Results

Fig. 2 shows the first three readouts, all readouts and the resulting sampling densities for Seiffert spiral protocols with and without the gradient axis cycling scheme. Histograms serving as proxy-measures of sample point distributions are equal in all three dimensions and more uniform for gradient axis cycled spirals, whereas normally rotated spirals show accumulations of point clusters, leading to coherent artifacts.Fig. 3 shows simulated Shepp-Logan phantoms and PSFs for both 3D-cones and Seiffert spiral protocols. While there is a significant loss of detail across both, Seiffert spiral sampled images better retain contrast of key structures. The images also exhibit higher SNR (53 vs 45).

Discussion and Conclusion

We present initial simulation results on a potential protocol for fast, functional 23Na-MRI with 3D Seiffert spiral sampling. Images of the 3D Shepp-Logan in silico phantom exhibit higher geometry fidelity and SNR, compared to 3D-cones. This is key for further reductions in TR and flip angle for increasing readouts.Further work will involve implementation of compressed-sensing reconstruction algorithms, essential to reduce undersampling artifacts, as18. Moreover, implementing quantitative strategies to assess trajectory effects on SNR will allow us to further optimize the protocol, including assessing the effect of $$$m$$$ on some coherent undersampling artifacts, visible in the PSF side lobes.

Finally, we also plan to incorporate temporal changes of sodium concentration4,5 into simulations to test sensitivity, leading toward a demonstration of 23Na-MRI acquisition with Seiffert spirals in vivo on a 3T Philips lngenia CX (Philips Healthcare, Best, The Netherlands). Ultimately, the aim is to create a highly efficient, versatile sequence that can be adapted to various 23Na-MRI applications.

Acknowledgements

SR: EPSRC-funded UCL Centre for Doctoral Training in Intelligent, Integrated Imaging in Healthcare (i4health) (EP/S021930/1) and the Department of Health’s NIHR-funded Biomedical Research Centre at University College London Hospitals.

CAMGWK: Horizon2020 (Human Brain Project SGA3, Specific Grant Agreement No. 945539), BRC (#BRC704/CAP/CGW), MRC (#MR/S026088/1), Ataxia UK, MS Society (#77), Wings for Life (#169111). CGWK is a shareholder in Queen Square Analytics Ltd.

BSS: Wings for Life (#169111).

References

[1] K. R. Thulborn, "Quantitative sodium MR imaging: A review of its evolving role in medicine," NeuroImage, vol. 168, pp. 250-268, 2018.

[2] G. Madelin, J.-S. Lee, R. R. Regatte and A. Jerschow, "Sodium MRI: Methods and applications," Progress in Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy, vol. 79, pp. 14-47, 2014.

[3] M. Bydder, W. Zaaraoui, B. Ridley, M. Soubrier, M. Bertinetti, S. Confort-Gouny, L. Schad, M. Guye and J.-P. Ranjeva, "Dynamic 23Na MRI - A non-invasive window on neuroglial-vascular mechanisms underlying brain function," NeuroImage, vol. 184, p. 771–780, January 2019.

[4] C. A. M. G. Wheeler-Kingshott, F. Riemer, F. Palesi, A. Ricciardi, G. Castellazzi, X. Golay, F. Prados, B. Solanky and E. U. D'Angelo, "Challenges and Perspectives of Quantitative Functional Sodium Imaging (fNaI)," Frontiers in Neuroscience, vol. 12, November 2018.

[5] A. Zylbertal, Y. Yarom and S. Wagner, "The Slow Dynamics of Intracellular Sodium Concentration Increase the Time Window of Neuronal Integration: A Simulation Study," Frontiers in Computational Neuroscience, vol. 11, September 2017.

[6] W. D. Rooney and C. S. Springer, "A comprehensive approach to the analysis and interpretation of the resonances of spins 3/2 from living systems," NMR in Biomedicine, vol. 4, p. 209–226, October 1991.

[7] F. J. Kratzer, S. Flassbeck, S. Schmitter, T. Wilferth, A. W. Magill, B. R. Knowles, T. Platt, P. Bachert, M. E. Ladd and A. M. Nagel, "3D sodium (23Na) magnetic resonance fingerprinting for time-efficient relaxometric mapping," Magnetic Resonance in Medicine, vol. 86, p. 2412–2425, June 2021.

[8] S. Konstandin and A. M. Nagel, "Measurement techniques for magnetic resonance imaging of fast relaxing nuclei," Magnetic Resonance Materials in Physics, Biology and Medicine, vol. 27, p. 5–19, July 2013.

[9] A. M. Nagel, F. B. Laun, M.-A. Weber, C. Matthies, W. Semmler and L. R. Schad, "Sodium MRI using a density-adapted 3D radial acquisition technique," Magnetic Resonance in Medicine, vol. 62, p. 1565–1573, October 2009.

[10] S. Nielles-Vallespin, M.-A. Weber, M. Bock, A. Bongers, P. Speier, S. E. Combs, J. Wöhrle, F. Lehmann-Horn, M. Essig and L. R. Schad, "3D radial projection technique with ultrashort echo times for sodium MRI: Clinical applications in human brain and skeletal muscle," Magnetic Resonance in Medicine, vol. 57, p. 74–81, 2006.

[11] J. G. Pipe, N. R. Zwart, E. A. Aboussouan, R. K. Robison, A. Devaraj and K. O. Johnson, "A new design and rationale for 3D orthogonally oversampled k-space trajectories," Magnetic Resonance in Medicine, vol. 66, p. 1303–1311, April 2011.

[12] F. E. Boada, J. S. Gillen, G. X. Shen, S. Y. Chang and K. R. Thulborn, "Fast three dimensional sodium imaging," Magnetic Resonance in Medicine, vol. 37, pp. 706-715, 1997.

[13] P. T. Gurney, B. A. Hargreaves and D. G. Nishimura, "Design and analysis of a practical 3D cones trajectory," Magnetic Resonance in Medicine, vol. 55, pp. 575-582, 2006.

[14] F. Riemer, B. S. Solanky, C. Stehning, M. Clemence, C. A. M. Wheeler-Kingshott and X. Golay, "Sodium (23Na) ultra-short echo time imaging in the human brain using a 3D-Cones trajectory," Magnetic Resonance Materials in Physics, Biology and Medicine, vol. 27, p. 35–46, 01 February 2014.

[15] M. Lustig, D. Donoho and J. M. Pauly, "Sparse MRI: The application of compressed sensing for rapid MR imaging," Magnetic Resonance in Medicine, vol. 58, p. 1182–1195, 2007.

[16] T. Speidel, P. Metze and V. Rasche, "Efficient 3D Low-Discrepancy k-Space Sampling Using Highly Adaptable Seiffert Spirals," IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging, vol. 38, p. 1833–1840, August 2019.

[17] C. R. Wyatt and A. R. Guimaraes, "3D MR fingerprinting using Seiffert spirals," Magnetic Resonance in Medicine, vol. 88, p. 151–163, March 2022.

[18] R. B. Olin, T. Speidel, J. D. Sanchez, E. S. Hansen, C. Laustsen, L. G. Hanson, V. Rasche and J. H. Ardenkjær-Larsen, "Seiffert spirals for hyperpolarized 13C MRI with efficient k-space sampling and flexible acceleration," 2022.

[19] P. Erdös, "Spiraling the Earth with C. G. J. Jacobi," American Journal of Physics, vol. 68, p. 888–895, October 2000.

[20] M. Lustig, S.-J. Kim and J. M. Pauly, "A fast method for designing time-optimal gradient waveforms for arbitrary k-space trajectories," IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging, vol. 27, p. 866–873, June 2008.

[21] J.-R. Liao, J. M. Pauly, T. J. Brosnan and N. J. Pelc, "Reduction of motion artifacts in cine MRI using variable-density spiral trajectories," Magnetic Resonance in Medicine, vol. 37, p. 569–575, April 1997.

[22] R. Stobbe and C. Beaulieu, "Advantage of sampling density weighted apodization over postacquisition filtering apodization for sodium MRI of the human brain," Magnetic Resonance in Medicine, vol. 60, p. 981–986, October 2008.

[23] A. H. Barnett, J. Magland and L. af Klinteberg, "A Parallel Nonuniform Fast Fourier Transform Library Based on an Exponential of Semicircle Kernel," SIAM Journal on Scientific Computing, vol. 41, p. C479–C504, January 2019.

[24] N. R. Zwart, K. O. Johnson and J. G. Pipe, "Efficient sample density estimation by combining gridding and an optimized kernel," Magnetic Resonance in Medicine, vol. 67, p. 701–710, June 2011.

[25] A. Coste, F. Boumezbeur, A. Vignaud, G. Madelin, K. Reetz, D. L. Bihan, C. Rabrait-Lerman and S. Romanzetti, "Tissue sodium concentration and sodium T1 mapping of the human brain at 3 T using a Variable Flip Angle method," Magnetic Resonance Imaging, vol. 58, p. 116–124, May 2019.

Figures