3428

GDCNet: deep learning model for self-consistent geometric distortion correction of EPI images without a field map

Marina Manso Jimeno1,2, John Thomas Vaughan1,2, and Sairam Geethanath2,3

1Department of Biomedical Engineering, Columbia University, New York, NY, United States, 2Columbia Magnetic Resonance Research Center, Columbia University, New York, NY, United States, 3The Biomedical Engineering Institute (Department of Diagnostic, Molecular and Interventional Radiology), Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, NY, United States

1Department of Biomedical Engineering, Columbia University, New York, NY, United States, 2Columbia Magnetic Resonance Research Center, Columbia University, New York, NY, United States, 3The Biomedical Engineering Institute (Department of Diagnostic, Molecular and Interventional Radiology), Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, NY, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Artifacts, fMRI, Geometrid Distortion, B0 inhomogeneity

GDCNet is a “self-consistent” deep learning (DL) model for distortion correction of EPI fMRI images and field map estimation. It only requires the EPI images for correction, saving acquisition time and avoiding motion-related correction errors. The two supervised U-Nets for forward modelling and distortion correction have been tested in silico and in vivo on a publicly-available and a prospectively-acquired dataset. The in silico models demonstrated generalization capabilities and achieved a mean RMSE of 2.56 x10-2 as self-conistency metric. Inference in vivo showed modest correction in the prefrontal cortex and similar estimated field map compared to the acquired ground truth.Introduction

Echo planar imaging (EPI)’s high temporal resolution makes it the trajectory of choice for functional MRI due to its sensitivity to BOLD signal changes1. However, phase errors accumulate along its long readout duration, causing geometric distortions and signal loss in areas of local field inhomogeneities such as air-tissue interfaces2. State-of-the-art correction methods leverage a voxel shift map (VSM) to mitigate distortions and intensity errors3. For its calculation a double echo-time GRE field map or two sets of EPI images with opposite phase encoding direction4 are required. Both approaches are time-consuming as they require one additional sequence acquisition. Furthermore, the long acquisition times characteristic of fMRI make it prone to subject motion during or between sequences, leading to registration errors and potential inaccuracies during distortion correction5. For these reasons, most studies do not perform any distortion correction. Within the 25 most downloaded fMRI datasets in OpenNeuro6, only 23% include a field map, and 9% double-encoded EPI data. Here we present GDCNet, a “self-consistent” deep learning (DL) model for distortion correction of EPI fMRI images. This method only requires the raw EPI images for correction, saving acquisition time and avoiding motion-related correction errors.Methods

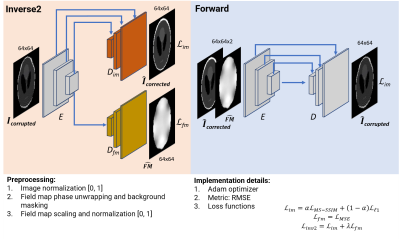

We trained two types of supervised U-Nets7 to learn geometric distortion correction (inverse2) and forward simulation using Tensorflow-Keras8. Figure 1 shows both model architectures and the implementation details. We leveraged two datasets for the models training, validation, and testing. First, we experimented on an in silico dataset generated using a 3D Shepp-Logan phantom corrupted using OCTOPUS9 along a 64x64 single-shot EPI trajectory with different field maps and off-resonance ranges of up to ±250 Hz. Second, we trained two other models using retrospective in vivo BOLD fMRI data and the corresponding field map from 10 subjects of an OpenNeuro dataset10. For both datasets, we generated 10,000 slices and split 80-20% among the training and testing sets. Additionally, 20% of the training sets were used for validation. The multi-frequency interpolation (MFI)11 and FSL’s FUGUE12 corrected images, together with the field maps, were used as ground truth for the in silico and in vivo inverse2 models, respectively. We experimented with FUGUE’s intensity correction option but opted to avoid it due to poor performance. We concatenated the in silico models (inverse2forward) to ensure correction ¨self-consistency¨ and calculated the RMSE between input and output. This experiment aimed at model expainability. Finally, we tested the in vivo inverse2 model on a prospective dataset acquired on a GE 3T scanner. We also acquired a field map for this experiment to compare with the predictions of the model.Results and discussion

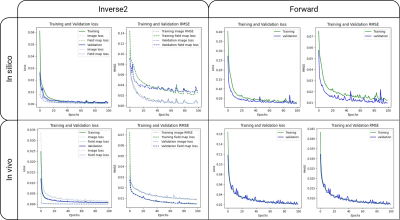

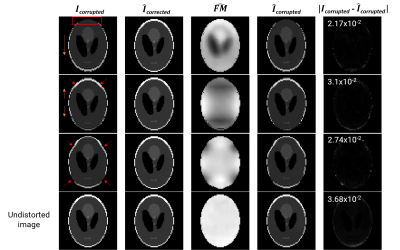

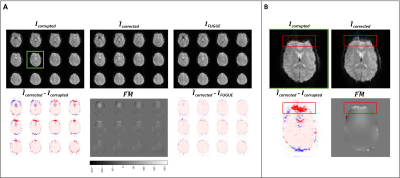

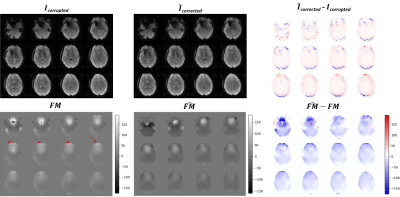

After training each model for 100 epochs (Figure 2) we evaluated their performance on the test sets. The hyperparameters used for the loss functions were ɑ=0.84 and λ=3. The in silico inverse2 model achieved 0.009 loss and RMSE values of 0.0061 and 0.0085 for the image, and field map outputs, respectively, while the forward model obtained 0.0235 loss and 0.0095 RMSE. The in vivo inverse2 model reached 0.0436 loss, image RMSE of 0.0095, and field map RMSE of 0.0049 whereas the forward model obtained 0.021 loss and 0.007 RMSE. Figure 3 shows in silico inference cases concatenating the inverse2 and forward models for different types of field maps and distortions. We chose to use a DL model (forward) to explain the results and ensure the self-consistency of the inverse2 model for processing speed reasons. Forward modelling using the forward DL model took 1 second for 2,000 slices while OCTOPUS takes 41 minutes. The mean RMSE between $$$I_{corrupted}$$$ and $$$\hat{I}_{corrected}$$$ was 2.56x10-2±0.0098 and 1.23x10-2±0.004 for the in silico and in vivo test sets, repectively. Furthermore, we confirmed the generalization capabilities of the in silico models by feeding them the undistorted Shepp-Logan phantom image, which resulted in no distortion and a uniform field map with 0 off-resonance from the inverse2 model. The forward model induced some ringing artifact characteristic of the MFI-corrected images used as ground truth during training.In vivo inference outputs (Figure 4-5) show modest geometric accuracy recovery in the orbitofrontal prefrontal cortex. The difference images between the inverse2 inputs and outputs show higher voxel displacement (red and blue pixels) in areas of the field map with higher off-resonance values. The correction performance, however, is limited to FUGUE’s performance as these correction results have been used as ground truth during training. Figure 4B shows how the model recovers the distorted frontal region but the intensity of the recovered voxels is not correct. Current work includes bypassing these ground-truth limitations and improving generalization and performance of the inverse2 model on prospective data (Figure 5) by implementing smoothness constraint into the field map branch loss function. The acquired and estimated field maps are similar overall although they present a slight difference in magnitude. The acquired field map is smoother and shows higher off-resonance in the prefrontal region (red arrows in Figure 5) where geometric distortions occur.

Conclusion

GDCNet demonstrated good performance and self-consistency in silico and in a retrospective in vivo dataset. The benefit of using this approach includes the ability of geometric distortion correction of EPI fMRI data without any extra sequence acquisition.Acknowledgements

This study was funded [in part] by the Seed Grant Program for MR Studies and the Technical Development Grant Program for MR Studies of the Zuckerman Mind Brain Behavior Institute at Columbia University and Columbia MR Research Center site.References

- Glover GH. Overview of functional magnetic resonance imaging. Neurosurgery Clinics. 2011 Apr 1;22(2):133-9.

- Deichmann R, Gottfried JA, Hutton C, Turner R. Optimized EPI for fMRI studies of the orbitofrontal cortex. Neuroimage. 2003 Jun 1;19(2):430-41.

- Abreu R, Duarte JV. Quantitative Assessment of the Impact of Geometric Distortions and Their Correction on fMRI Data Analyses. Frontiers in Neuroscience. 2021 Mar 9;15:642808.

- Jezzard P. Correction of geometric distortion in fMRI data. Neuroimage. 2012 Aug 15;62(2):648-51.

- Schallmo MP, Weldon KB, Burton PC, Sponheim SR, Olman CA. Assessing methods for geometric distortion compensation in 7 T gradient echo functional MRI data. Human Brain Mapping. 2021 Sep;42(13):4205-23.

- https://openneuro.org/

- Ronneberger O, Fischer P, Brox T. U-net: Convolutional networks for biomedical image segmentation. International Conference on Medical image computing and computer-assisted intervention 2015 Oct 5 (pp. 234-241). Springer, Cham.

- Abadi M, Agarwal A, Barham P, Brevdo E, Chen Z, Citro C, Corrado GS, Davis A, Dean J, Devin M, Ghemawat S. Tensorflow: Large-scale machine learning on heterogeneous distributed systems. arXiv preprint arXiv:1603.04467. 2016 Mar 14.

- Manso Jimeno M, Vaughan JT, Geethanath S. Off-resonance CorrecTion OPen soUrce Software (OCTOPUS). Journal of Open Source Software. 2021 Mar 4;6(59):2578.

- Thompson WH, Nair R, Oya H, Esteban O, Shine JM, Petkov CI, Poldrack RA, Howard M, Adolphs R. Human es-fMRI Resource: Concurrent deep-brain stimulation and whole-brain functional MRI. OpenNeuro. 2021 [ds002799].

- Man LC, Pauly JM, Macovski A. Multifrequency interpolation for fast off‐resonance correction. Magnetic resonance in medicine. 1997 May;37(5):785-92.

- Jezzard P, Balaban RS. Correction for geometric distortion in echo planar images from B0 field variations. Magnetic resonance in medicine. 1995 Jul;34(1):65-73.

Figures

Figure 1. Model architectures, preprocessing steps, and implementation details of the inverse2 and forward U-Nets. The inverse2 U-Net decoding path splits into two branches, the image branch with skip connections from the encoding path and the field map branch.

Figure 2. Training and validation loss and metric curves of the inverse2 and forward models after 100 epochs. The inverse2 loss and RMSE plots show both the image and field map curves.

Figure 3. Inference results of the inverse2forward model. From columns left to right: input to the inverse2 model where the rectangle and arrows point to the distortions and direction of contraction/stretching, inverse2 image output, inverse2 field map output, and output of the forward model using columns 2 and 3 as input. The fifth column is the absolute difference image between columns 1 and 4 with the corresponding RMSE value in the top-left corner. The last row shows the results of using an undistorted image as input to the inverse2forward model.

Figure 4. Inference results of the inverse2 in vivo model. Panel A: inverse2 input and outputs and difference image between the output and input, and output and ground truth (FUGUE) images. Panel B: inference results of a single slice for better visualization (slice within the green square in Panel A). The red rectangles highlight the areas where distortion and correction are more noticeable, agreeing with areas of higher intensity in the predicted field map.

Figure 5. Inference results of the inverse2 in vivo model using a prospective dataset. Top row: raw corrupted EPI images, EPI images after geometric inverse2 distortion correction, and the difference between the two. Bottom row: acquired field map in Hertzs, estimated field map by inverse2 in Hertzs, and the difference between the two. The two field maps are similar overall although they present a slight difference in magnitude. The acquired field map is smoother and shows higher off-resonance in the prefrontal region (red arrows) where geometric distortions occur.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.58530/2023/3428