3426

Large-scale simulation of rigid head motion artifacts in whole brain MRI data and the impact on automatic cortical segmentation1Berlin Ultrahigh Field Facility (B.U.F.F.), Max Delbrück Center for Molecular Medicine in the Helmholtz Association, Berlin, Germany, 2Experimental and Clinical Research Center, a joint cooperation between the Charitë Medical Faculty and the Max Delbrück Center for Molecular Medicine in the Helmholtz Association, Berlin, Germany, 3Digital Health & Machine Learning Research Group, Hasso Plattnet Institut for Digital Engineering, Potsdam, Germany, 4Hasso Plattner Institute for Digital Health at Mount Sinai, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, NY, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Artifacts, Artifacts

MRI datasets from epidemiological studies such as the German National Cohort (GNC) are increasingly used in machine learning. These datasets show a lower prevalence of motion artifacts than encountered in clinical practice. We simulated realistic motion artifacts caused by rigid head motion on the GNC MR data (50 subjects) by modifying the TorchIO data augmentation framework. Five levels of artifact severity were simulated. We benchmarked our results to empirical measurements using the standard GNC MPRAGE imaging protocol. The robustness to motion of FreeSurfer and SynthSeg for cortical segmentation was investigated, indicating an improved performance using SynthSeg.

Introduction

Image artifacts due to subject motion are a very common problem in MRI1. While a plethora of correction techniques exists2, none are typically employed in routine structural T1-weighted imaging of the head. The uneven distribution of motion artifacts across groups3, 4 introduces biases, not least in machine learning-based approaches5. Homogenous datasets from epidemiological studies often need to undergo data augmentation6. e.g. by simulating motion artifacts7. Given that the exact k-space sampling pattern is known, physically realistic simulations of a specified motion pattern can be performed on unreconstructed (typically multi-coil) MR data. However, raw k-space data is rarely available for large-scale population MRI datasets such as the German National Cohort8 (GNC) or the UK Biobank9. Thus, there is a need to simulate realistic head motion artifacts using only DICOM magnitude data. Here, we suggest an adaption to an existing data preprocessing and augmentation framework, TorchIO10, to generate more realistic motion artifacts than what is possible from the out-of-the-box functionality. We benchmark our results against images from experiments where the subject was instructed to move under controlled conditions. We further evaluate the effect of our simulations on cortical segmentation using two automatic brain segmentation tools.Methods

A healthy subject (31 years, male) was scanned on a 3T Magnetom Skyra Fit (Siemens, Erlangen, Germany) using a 32-channel head RF coil (Siemens, Erlangen, Germany) for reception after giving informed written consent. The GNC protocol was used for 3D MPRAGE acquisition of the brain: α = 9°, TE/TR/TI/TC = 2.98/7.1/900/2200 ms, TF = 224, 1 mm isotropic resolution, GRAPPA = 2 in the inner loop AP direction, Tacq = 5:07 min. Three scans were performed where the subject was instructed via speaker system to: (1) periodically nod every 30 s (2 nods/min), (2) periodically nod every 15 s (4 nods/min), and (3) stay still. Motion simulations were then performed on the latter motion-free image volume and benchmarked to one of the two motion-corrupted images. The original TorchIO motion augmentation was adapted to allow a non-random motion paradigm with well-defined timings, movements, and phase encoding direction. The duration of each simulated movement was normalized to only the part of the sequence where data was actually acquired, rather than Tacq which includes periods of free relaxation. Based on an ROI analysis of the three image volumes, an empirical linear model for adding Gaussian noise was implemented to mimic the reduction in SNR with increasing nodding frequency. The simulated pitch, p, and duration, tdur, of the nodding motion was varied as 10° ≤ p ≤ 20° and 1.5 s ≤ tdur ≤ 3.5 s until the resulting images were deemed visually similar to the real motion-corrupted data. The finished pipeline was then applied to 50 GNC subjects at 5 simulated nodding frequencies of 2, 2.4, 3, 4 and 6 nods/min. Cortical segmentation was performed on the motion-corrupted and motion-free (5+1) × 50 = 300 image volumes using FreeSurfer11 and SynthSeg12. The Dice coefficient of the segmentation obtained on the motion-corrupted volume in relation to the motion-free reference segmentation was calculated and compared for each nodding frequency and both segmentation tools.Results

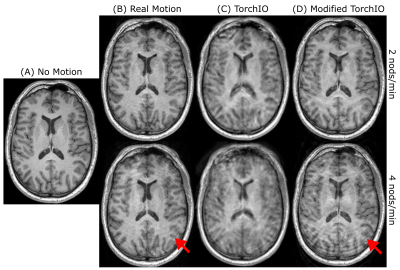

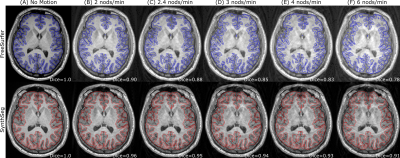

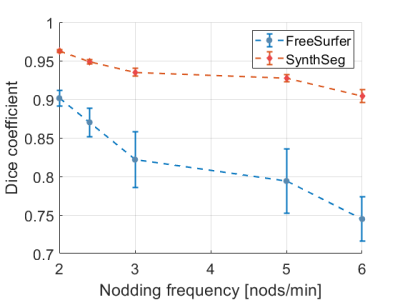

Figure 1 shows a comparison between the real artifacts obtained during the controlled motion experiment and the simulations obtained using either the out-of-the-box functionality of TorchIO or with our modifications. The volumes acquired during subject motion show well-defined high-spatial frequency ringing in the outer cortical areas that increased in prominence as the nodding frequency increased while the deep brain remained largely unaffected. A simulated pitch of p = 15° and nodding duration of tdur = 2.5 s yielded the closest result to the ground truth of real motion artifacts. Motion augmentation with the unmodified TorchIO showed general blurring and ghosting across the whole volume with less prominent ringing artifacts. In contrast, our modification resulted in less blurring but with emphasized cortical ringing, thereby better representing the real artifacts. Cortical segmentation using FreeSurfer was much more affected by the simulated motion artifacts compared to SynthSeg (Figure 2) as illustrated by a stronger decrease in the average Dice coefficient as well as a higher standard deviation among subjects (Figure 3).Discussion

TorchIO is a useful testbed and framework for standardizing data augmentation for machine learning applications in medical imaging. However, the functionalities to induce MRI-specific artifacts do not realistically correspond to the artifacts arising from a common type of motion (periodic nodding) in conjunction with a standard brain MRI protocol (MPRAGE). TorchIO is limited because it uses magnitude image data, rather than unreconstructed k-space data. Here we show that, despite this shortcoming, more realistic results are obtainable. Simulated motion was restricted to periodic nodding which is well-motivated since it is the most common type of rigid head motion13, 14. We further note that when forced to work with motion-corrupted brain MRI data, SynthSeg might be a better alternative than FreeSurfer for cortical segmentation purposes.Conclusions

An approach to perform realistic and large-scale simulations of head motion with varying severity using only magnitude data was implemented. Automated cortical segmentation with SynthSeg appears to be less impacted by rigid head motion induced artifacts than FreeSurfer.Acknowledgements

This research is supported through the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) within the project ‘Syreal’ (Grant No. 01/S21069A).

References

1. Andre JB, Bresnahan BW, Mossa-Basha M, Hoff MN, Smith CP, Anzai Y, et al. Toward Quantifying the Prevalence, Severity, and Cost Associated With Patient Motion During Clinical MR Examinations. J Am Coll Radiol. 2015;12(7):689-95.

2. Zaitsev M, Maclaren J, Herbst M. Motion artifacts in MRI: A complex problem with many partial solutions. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2015;42(4):887-901.

3. Haller S, Monsch AU, Richiardi J, Barkhof F, Kressig RW, Radue EW. Head motion parameters in fMRI differ between patients with mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer disease versus elderly control subjects. Brain Topogr. 2014;27(6):801-7.

4. Siegel JS, Mitra A, Laumann TO, Seitzman BA, Raichle M, Corbetta M, et al. Data Quality Influences Observed Links Between Functional Connectivity and Behavior. Cereb Cortex. 2017;27(9):4492-502.

5. Nielsen AN, Greene DJ, Gratton C, Dosenbach NUF, Petersen SE, Schlaggar BL. Evaluating the Prediction of Brain Maturity From Functional Connectivity After Motion Artifact Denoising. Cereb Cortex. 2019;29(6):2455-69.

6. Shorten C, Khoshgoftaar TM. A survey on Image Data Augmentation for Deep Learning. J Big Data-Ger. 2019;6(1).

7. Shaw R, Sudre CH, Varsavsky T, Ourselin S, Cardoso MJ. A k-Space Model of Movement Artefacts: Application to Segmentation Augmentation and Artefact Removal. IEEE transactions on medical imaging. 2020;39(9):2881-92.

8. Bamberg F, Kauczor HU, Weckbach S, Schlett CL, Forsting M, Ladd SC, et al. Whole-Body MR Imaging in the German National Cohort: Rationale, Design, and Technical Background. Radiology. 2015;277(1):206-20.

9. Sudlow C, Gallacher J, Allen N, Beral V, Burton P, Danesh J, et al. UK biobank: an open access resource for identifying the causes of a wide range of complex diseases of middle and old age. PLoS Med. 2015;12(3):e1001779.

10. Perez-Garcia F, Sparks R, Ourselin S. TorchIO: A Python library for efficient loading, preprocessing, augmentation and patch-based sampling of medical images in deep learning. Computer methods and programs in biomedicine. 2021;208:106236.

11. Reuter M, Schmansky NJ, Rosas HD, Fischl B. Within-subject template estimation for unbiased longitudinal image analysis. NeuroImage. 2012;61(4):1402-18.

12. Billot B, Colin M, Arnold SE, Das S, Iglesias JE. Robust Segmentation of Brain MRI in the Wild with Hierarchical CNNs and no Retraining. 2022.

13. Frew S, Samara A, Shearer H, Eilbott J, Vanderwal T. Getting the nod: Pediatric head motion in a transdiagnostic sample during movie- and resting-state fMRI. PloS one. 2022;17(4):e0265112.

14. Power JD, Barnes KA, Snyder AZ, Schlaggar BL, Petersen SE. Spurious but systematic correlations in functional connectivity MRI networks arise from subject motion. NeuroImage. 2012;59(3):2142-54.

Figures

Figure 1. Real motion and motion simulations at a nodding frequency of 2 nods/min (top row) or 4 nods/min (bottom row). (A) Motion-free volume used as baseline for motion simulations. (B) Motion-corrupted volumes acquired during movement in the scanner. (C) Simulated motion-corrupted volumes using the out-of-the-box TorchIO augmentation. (D) Simulated motion-corrupted volumes using our modified TorchIO augmentation. Cortical ringing (red arrows) is better represented by our simulations.

Figure 2. Example MPRAGE from the GNC dataset (A) augmented with simulated motion artifacts at a nodding frequency of 2/2.4/3/4/6 nods/min (B/C/D/E/F) and resulting cortical segmentations using either FreeSurfer (top row) or SynthSeg (bottom row). The Dice coefficient of the segmentations in (B)-(F) in relation to the segmentation in (A) was 0.90/0.88/0.85/0.83/0.78 for FreeSurfer and 0.96/0.95/0.94/0.93/0.91 for SynthSeg.

Figure 3. Decrease in cortical segmentation quality with increasing nodding frequency visualized through the Dice coefficient. FreeSurfer (blue circles) was much more affected by the simulated motion artifacts than SynthSeg (red diamonds), both in terms of a decreasing average Dice coefficient as well as an increasing standard deviation between subjects.