3416

Effect of chemical shift displacement on Lipid Composition determination in localized 1H NMR Spectroscopy1Nutrition & Movement Sciences, Maastricht University, Maastricht, Netherlands, 2Radiology & Nuclear Medicine, Maastricht University Medical Center, Maastricht, Netherlands, 3Scannexus, Maastricht, Netherlands, 4Faculty of Health Medicine & Life Sciences, Maastricht University, Maastricht, Netherlands, 5German Diabetes Center, Düsseldorf, Germany

Synopsis

Keywords: Artifacts, Spectroscopy, Chemical Shift Displacement

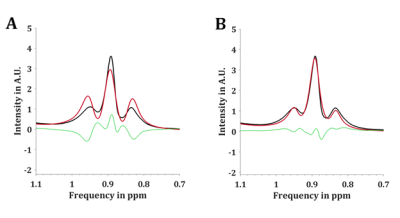

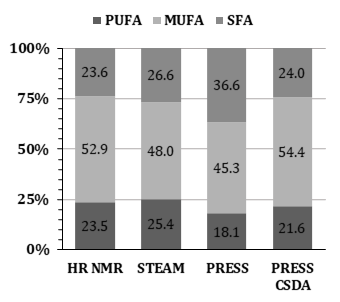

We showed that implementing prior knowledge about Chemical Shift Displacement Artifacts (CSDA) in localized MR-spectroscopy improves fit quality in the context of hepatic lipid composition measurements (LICO) performed with PRESS. Residuals of fitting PRESS spectra of peanut oil with CSDA prior knowledge show smaller residuals compared to assuming a purely Spin Echo based J-coupling evolution during the echo time. Furthermore, peanut oil LICO measured by PRESS and fitted with CSDA prior knowledge almost matched reference values determined by HR-NMR (PUFAHR-NMR = 23.5%, MUFAHR-NMR = 52.9%, SFAHR-NMR = 23.6% vs. PUFACSDA = 21.57%, MUFACSDA = 54.4%, SFACSDA = 24.0%).Introduction:

Liver fat content (IHL) and lipid composition (LICO) give insight into metabolic health and have been shown to be associated with risks of developing metabolic disease (1)(2). Recently, a method to non-invasively determine LICO was established and uses 1H MRS STEAM at a field strength of 3T in combination with prior knowledge based peak fitting deduced from high field NMR (1). However, the application of this method is difficult in individuals with low fat content (<1%). Theoretically, PRESS would also be suited for this purpose and as the SNR is two-fold higher (3), would make it possible to determine fatty acid composition at a lower liver fat content. However, PRESS is more prone to Chemical Shift Displacement Artifacts (CSDA) than STEAM due to smaller RF pulse bandwidths (4). This increasingly affects the shape and signal intensity of coupled resonances the further away they are from F0 (4). IHLC calculations rely on the accurate quantification of Methyl, Allylic, Bis-Allylic and α-Methylene resonances in 1H spectra (1). All of those resonances are J-coupled and create a complex phase pattern due to incomplete refocusing by CSDA, which leads to inaccuracies in their quantification (4). Attempts to limit the creation of complex phase patterns by CSDA employ broader pulse bandwidths and/or stronger pulse gradients. However, this can quickly lead to high energy deposition that exceeds the Specific Absorption Rate (SAR) limits. Instead, we propose to implement the complex phase coupling patterns and signal loss into the fitting model.Methods:

High resolution 1H NMR spectra of peanut oil were measured in a 700 MHz Bruker Avance III (Bruker Corporation, Billerica, Massachusetts, USA) to identify relative chemical shifts and J-coupling constants of peanut oil. Therefore, FIDs with the following parameters were acquired: Solvent: CDCl3, T = 298K, TR = 30s, acquired data points = 111606, NSA = 64, spectral bandwidth = 11161Hz. The HR-NMR results were then used to generate an artificial spectrum in MATLAB (MATLAB 2021b, The MathWorks, Inc.), which also contains the complex phase patterns resulting from CSDA calculated from the given J-coupling patterns, PRESS pulse bandwidths and timings. The resulting artificial spectrum was then iteratively adjusted to match spectral linewidth, amplitudes, chemical shifts as well as zero order phase of peanut oil spectra acquired on a 3T Philips Achieva MRI system (Philips, Best, The Netherlands). Spectra were acquired with a standard Philips cardiac coil by PRESS and STEAM with a voxel size of 20mm x 20mm x 20mm, TE = 30ms, TR = 4500ms, acquired data points = 2048, 16 step phase cycling, PRESS pulse bandwidth: π/2 = 1360Hz; π = 1263Hz, STEAM pulse bandwidth: π/2 = 1536Hz on the 3T system. PRESS spectra were acquired with NSA = 16 and STEAM spectra with NSA = 32. The mixing time of STEAM was kept as short as possible with TM = 9.4ms. F0 of PRESS and STEAM acquisitions was manually set to 4.7ppm due to a lack of an internal water reference in peanut oil. In addition, PRESS and STEAM with the above mentioned settings were also used to acquire spectra of a water phantom loaded with 0.9% NaCl. Eddy current phase artifacts were then extracted from the respective water spectra and corrected for in peanut oil spectra. Peanut oil LICO was determined in HR-NMR, as well as in PRESS and STEAM spectra. In case of HR-NMR spectra, regions of interest for methylene, allylic, olefinic and bis-allylic resonances were integrated and LICO calculated using the formulas previously reported (1). PRESS and STEAM spectra from peanut oil were fitted using an in-house developed MATLAB script (1). PRESS spectra were furthermore fitted with complex phase patterns resulting from CSDA which were added to the fitting model. Furthermore, signal loss caused by CSDA was corrected for before LICO calculation.Results:

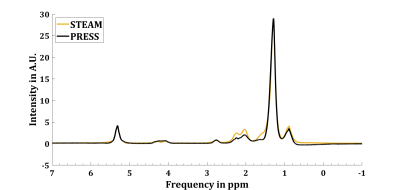

Figure 1 shows a comparison of acquired STEAM and PRESS spectra from peanut oil at 3T, whereby the STEAM spectrum was up scaled to match intensities of the PRESS spectrum. Uncoupled resonances show no deviations, coupled MUFA, PUFA and a-methylene resonances show lower intensities in PRESS compared to STEAM. LICO of HR-NMR (PUFAHR-NMR = 23.5%, MUFAHR-NMR = 52.9%, SFAHR-NMR = 23.6%) and STEAM (PUFASTEAM = 25.4%, MUFASTEAM = 48.0%, SFASTEAM = 26.6%). PRESS LICO (PUFAPRESS = 18.1%, MUFAPRESS = 45.3%, SFAPRESS = 36.6%) and PRESS LICO fitted with complex CSDA phase patterns and signal loss correction (PUFACSDA = 21.6%, MUFACSDA = 54.4%, SFACSDA = 24.0%). Figure 3 visualizes the resulting LICOs from all acquisition and quantification methods.Discussion & Conclusion:

Introducing complex phase patterns of coupled resonances caused by CSDA into the fitting model has improved overall fit quality in PRESS spectra. Furthermore, this improved LICO results of peanut oil as these got closer to the LICO from HR-NMR (ΔPUFAHRNMR-PRESS 1.9%; ΔMUFAHRNMR-PRESS = -1.5%; ΔSFAHRNMR-PRESS = 0.4%), even slightly better than STEAM LICO (ΔPUFAHRNMR-STEAM =1.9%; ΔMUFAHRNMR-STEAM = 4.9%; ΔSFAHRNMR-STEAM = -3.0%).Acknowledgements

No acknowledgement found.References

1. Roumans KHM, Lindeboom L, Veeraiah P, Remie CME, Phielix E, Havekes B, et al. Hepatic saturated fatty acid fraction is associated with de novo lipogenesis and hepatic insulin resistance. Nat Commun. 2020;11(1):1891.

2. Luukkonen PK, Sadevirta S, Zhou Y, Kayser B, Ali A, Ahonen L, et al. Saturated Fat Is More Metabolically Harmful for the Human Liver Than Unsaturated Fat or Simple Sugars. Diabetes Care. 2018;41(8):1732-9.

3. De Graaf RA. In vivo NMR spectroscopy: principles and techniques: John Wiley \& Sons; 2013. 4. Yablonskiy DA, Neil JJ, Raichle ME, Ackerman JJH. Homonuclear J coupling effects in volume localized NMR spectroscopy: pitfalls and solutions. Magnetic resonance in medicine. 1998;39(2):169--78.

Figures