3413

Optimised navigator correction of physiological field fluctuations in multi-echo GRE of the lumbar spinal cord at 3T

Laura Beghini1, Gergely David2,3, Martina D. Liechti3, Silvan Büeler3, and S. Johanna Vannesjo1

1Department of Physics, Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Trondheim, Norway, 2Spinal Cord Injury Center, Balgrist University Hospital, University of Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland, 3Dept. of Neuro-Urology, Balgrist University Hospital, University of Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland

1Department of Physics, Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Trondheim, Norway, 2Spinal Cord Injury Center, Balgrist University Hospital, University of Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland, 3Dept. of Neuro-Urology, Balgrist University Hospital, University of Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland

Synopsis

Keywords: Artifacts, Spinal Cord

Multi-echo GRE sequences acquired in the spinal cord are sensitive to breathing-related field variations, leading to ghosting artifacts. While navigator-based corrections are often used in the brain to account for field variations, standard implementations often fail in the spinal cord due to the close proximity to the lungs. Here, we investigated optimised navigator corrections including a fast Fourier transform combined with region selection encompassing the spinal canal. Besides a visual improvement of image quality, the optimised navigator correction yielded statistically significant improvements in the CNR between WM and CSF and the SNR in the WM.Introduction

Multi-echo gradient-echo (GRE) sequences are commonly used for anatomical imaging of the spinal cord, because they provide excellent contrast between grey matter (GM), white matter (WM), and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). One of their main limitations is the sensitivity to voluntary and involuntary motion, leading to ghosting artifacts and lower image quality even in compliant subjects. Time-varying B0 fields related to the breathing cycle(1,2) contribute substantially to the artifact load in the spinal cord. Navigator readouts(3) can be used to measure the B0 fluctuations allowing to demodulate the acquired signal before the image reconstruction. However, despite the potential advantage, navigators are rarely used in spinal cord imaging. This is likely because, compared to brain imaging, the navigator processing in the spinal cord is less robust due to (i) higher spatial variability of the breathing-induced fields due to the lung’s proximity(2), and (ii) larger signal magnitude variation between coils at late echo times. Standard navigator implementations often fail under these circumstances, which can even exacerbate artifacts. Therefore, there is a need for navigator processing specifically tailored to spinal cord imaging. In this study, we explore the effect of optimized processing pipelines for navigator-based correction on the image quality of a multi-echo GRE sequence acquired in the lumbosacral cord at 3T.Methods

Scanning was done on a 3T Siemens Prisma system and a 32-channel receive spine coil in ten healthy volunteers (3 females, age (mean±std): 33.5±10.3y). A 2D multi-echo GRE sequence was acquired covering the entire lumbosacral spinal cord with 18 axial-oblique slices (5 mm thickness, no gap, FOV=192x192 mm2, res=0.5x0.5 mm2, 4 echoes, TE=6.86/10.86/14.86/18.86 ms, TR=899 ms, flip angle=44°, R=2, 3 averages). A trace from the Siemens respiratory belt was recorded for nine of the subjects. After the last echo in each TR, a navigator was acquired reading out a single line through the centre of k-space. Siemens raw data were converted to ISMRMRD format using siemens_to_ismrmrd(4).Corrections based on three different navigator processing approaches (Figure 1) were applied before the image reconstruction, leading to four different pipelines:

- no nav: no navigator processing;

- k-nav: optimised k-space navigator processing;

- FFT-nav: navigator processing after Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) and region selection targeting the spinal cord (2.8 cm width);

- FFT-unwrap: FFT-nav with added phase unwrapping based on the respiratory trace.

$$SNR=\frac{\text{mean}(S)}{\text{std}(S)} \,, \quad CNR_{1/2}=\frac{|\text{mean}(S_1)-\text{mean}(S_2)|}{\sqrt{\text{std}^2(S_1)+\text{std}^2(S_2)}}\,.$$

Values were averaged across 5 slices around the lumbosacral enlargement. Differences in SNR and CNR among navigator corrections (no nav, FFT-nav, k-nav) were tested using repeated measures ANOVA, followed by post-hoc pairwise comparisons with Tukey’s correction for multiple comparisons. FFT-unwrap was not included in the comparison as it made a difference only in a few slices with wrapping artifacts and otherwise yielded identical results to FFT-nav.

Results

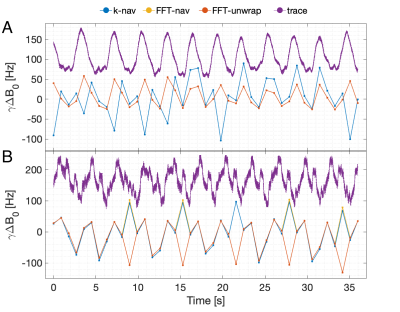

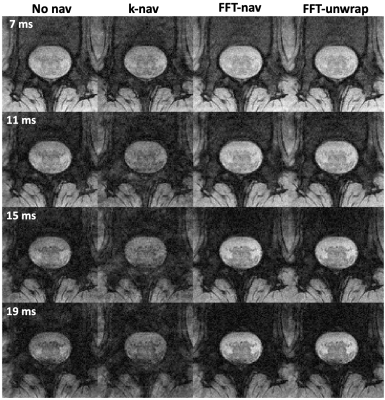

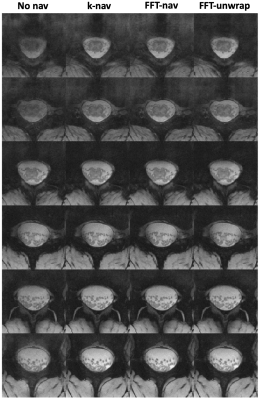

Breathing-induced B0 field variations, estimated from the navigators, showed the same pattern as the respiratory belt traces (Figure 2). These B0 fluctuations caused incoherent ghosting in the reconstructions without navigator correction, which became more severe at longer TE (Figure 3). Field variations and ghosting varied among slices and were the most severe in the superior slices (closer to the lungs). Both k-nav and FFT-nav reduced ghosting artifacts in at least some slices in all subjects. k-navigators occasionally yielded irregular phase estimates (Figure 2A), exacerbating the ghosting (Figure 3), but FFT-nav generally performed well even in these cases. In a few cases, an unwrapping step (FFT-unwrap) was necessary as the navigator estimates presented phase wrapping (Figure 2B and 4). Ghosting artifacts appeared less severe in the RMS images due to averaging across repetitions and echoes combination, but were still visibly reduced after navigator correction (Figure 4). Compared to "no nav", both k-nav and FFT-nav yielded higher CNR between WM and CSF ($$$p_{\text{k-nav}}^{\text{no nav}},\, p_{\text{FFT-nav}}^{\text{no nav}}<0.001$$$) and SNR in the WM ($$$p_{\text{k-nav}}^{\text{no nav}}=0.02,\, p_{\text{FFT-nav}}^{\text{no nav}}=0.008$$$) of the lumbosacral enlargement. There was also a trend toward higher CNR and SNR values with FFT-nav compared to the k-nav.Discussion and conclusion

Optimised navigator processing yields accurate estimates of breathing-induced field variations in 2D GRE acquisitions of the spinal cord. These estimates can be used to reduce breathing-induced ghosting artifacts. However, standard navigator processing frequently fails, exacerbating the artifacts. Conversely, when using the FFT navigator approach image quality improves considerably in most cases while staying similar in a few cases. The improved image quality could be used to (i) reduce the number of averages and the scan time, (ii) increase the repeatability, reproducibility, and reliability, including for quantitative assessments, (iii) improve automatic segmentation. The increased robustness associated with FFT-based navigators makes it attractive for clinical applications. Moreover, while the navigator processing was tested in the lumbar spinal cord, it is also expected to yield improvements in the cervical and thoracic regions.Acknowledgements

References

- Verma, T., & Cohen-Adad, J. (2014). Effect of respiration on the B0 field in the human spinal cord at 3T. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine, 72(6), 1629–1636. https://doi.org/10.1002/mrm.25075

- Vannesjo, S. J., Miller, K. L., Clare, S., & Tracey, I. (2018). Spatiotemporal characterization of breathing-induced B0 field fluctuations in the cervical spinal cord at 7T. NeuroImage, 167, 191–202. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2017.11.031

- Versluis, M. J., Peeters, J. M., van Rooden, S., van der Grond, J., van Buchem, M. A., Webb, A. G., & van Osch, M. J. P. (2010). Origin and reduction of motion and f0 artifacts in high resolution T2*-weighted magnetic resonance imaging: Application in Alzheimer’s disease patients. NeuroImage, 51(3), 1082–1088. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.03.048

- Inati SJ, Naegele JD, Zwart NR, Roopchansingh V, Lizak MJ, Hansen DC, Liu CY, Atkinson D, Kellman P, Kozerke S, Xue H, Campbell-Washburn AE, Sørensen TS, Hansen MS. ISMRM Raw data format: A proposed standard for MRI raw datasets. Magn Reson Med. 2017 Jan;77(1):411-421.

- Pruessmann, K. P., Weiger, M., Scheidegger, M. B., & Boesiger, P. (1999). SENSE: Sensitivity encoding for fast MRI. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine, 42(5), 952–962. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1522-2594(199911)42:5<952::AID-MRM16>3.0.CO;2-S

- Pruessmann, K. P., Weiger, M., Börnert, P., & Boesiger, P. (2001). Advances in sensitivity encoding with arbitrary k -space trajectories: SENSE With Arbitrary k -Space Trajectories. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine, 46(4), 638–651. https://doi.org/10.1002/mrm.1241

- Knopp, T., & Grosser, M. (2021). MRIReco.jl: An MRI reconstruction framework written in Julia. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine, 86(3), 1633–1646. https://doi.org/10.1002/mrm.28792

- Uecker, M., Lai, P., Murphy, M. J., Virtue, P., Elad, M., Pauly, J. M., Vasanawala, S. S., & Lustig, M. (2014).ESPIRiT — An Eigenvalue Approach to Autocalibrating Parallel MRI: Where SENSE meets GRAPPA. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine : Official Journal of the Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine / Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine, 71(3), 990–1001. https://doi.org/10.1002/mrm.24751

- Büeler, S., Yiannakas, M. C., Damjanovski, Z., Freund, P., Liechti, M. D., & David, G. (2022). Optimized multi-echo gradient-echo magnetic resonance imaging for gray and white matter segmentation in the lumbosacral cord at 3 T. Scientific Reports, 12(1), Article 1. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-20395-1

Figures

Figure 1: Methods pipeline. Three different pipelines were used to process the navigator data: (i) an optimized k-space based processing (k-nav); (ii) an FFT-based approach (FFT-nav), including region selection targeting the spinal cord; (iii) an FFT-nav processing with an added phase unwrapping step based on the respiratory belt recording (FFT-unwrap). After applying the navigator correction on the k-space image data, demodulating the signal, the images were reconstructed.

Figure 2: Navigator and respiratory belt trace. The temporal B0 field variations estimated with the k-space navigator, the FFT navigator and the FFT unwrapped navigator are displayed together with the respiratory belt trace recording. Panel A shows the data referring to subject 01, for the same repetition and slice displayed in Figure 3. No phase wrapping is present here, so FFT-unwrap overlaps FFT-nav. Panel B shows the data for one slice and one repetition acquired on subject 10 (Figure 4).

Figure 3: Reconstruction results for subject 01, showing four different echo times (TE) of one axial slice for a single average. The data were reconstructed with no navigator correction, k-space based navigator correction, FFT-based correction and FFT unwrapped correction. The navigator trace for this slice (Figure 2 A) does not present wrapping, therefore FFT-nav leads to the same result as FFT-unwrap.

Figure 4: Reconstruction results for subject 10, showing one in every three slices, starting from the upmost slice. Each image is obtained from averaging over three repetitions and root-mean-square (RMS) combination over four echoes. The images reconstructed with no navigator correction are compared with the k-nav, FFT-nav and FFT-unwrap images. The navigator data for the uppermost slices showed wrapping (Figure 2B) and the FFT-unwrap approach leads to the best visual results in these slices.

Figure 5: Quantitative analysis results averaged across 5 slices covering the lumbosacral enlargement, for all subjects. Signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) for white matter (WM) and grey matter (GM) are shown in the top row. Contrast-to-noise ratio (CMR) between WM and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), and between GM and WM, are shown in the bottom row. Each of the navigator approaches considerably improved the considered metrics. The difference between FFT-nav and k-nav is not statistically significant but FFT-nav shows a trend towards higher values i.e. better image quality.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.58530/2023/3413