3409

Slice-by-slice Dynamic Shimming Based on a Chemical Shift-Encoded Acquisition to Improve Fat Suppression in DWI1Medical Physics, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, WI, United States, 2Radiology, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, WI, United States, 3GE Healthcare, Waukesha, WI, United States, 4GE Healthcare, Menlo Park, CA, United States, 5GE Healthcare, Boston, MA, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Artifacts, Fat

B0 inhomogeneities can lead to failures in chemical shift-based fat suppression, particularly in complex susceptibility environments. Conventional volumetric shimming methods are frequently unable to compensate for these B0 inhomogeneities, which leads to residual fat signal and artifacts in various applications. We propose a slice-by-slice shimming method that relies on information (water-only image, fat-only image, B0 fieldmap) derived from a rapid chemical shift-encoded acquisition. This method demonstrated improved fat suppression in diffusion weighted imaging (DWI) of the upper leg and may lead to improved reliability in other applications.Introduction

Fat suppression is important in many MR imaging settings, including DWI based on echo-planar imaging, where unsuppressed fat signals appear shifted due to the large chemical shift artifact, and consequently may obscure the organs of interest. Chemical shift-based fat suppression is common in diffusion weighted imaging1 (DWI), but fails in the presence of substantial B0 inhomogeneities2. Importantly, chemical shift-based fat suppression failures are common in clinical practice and often lead to non-diagnostic image quality, particularly in the presence of a complex magnetic susceptibility environment such as the abdomen and lower extremities3. Slice specific shimming approaches4,5,6 and fieldmap-driven shimming methods7,8,9,10,11 have been proposed. However, slice-specific shimming for DWI may benefit from advanced chemical shift-encoding (CSE)-based information including the B0-fieldmap and distributions of water and fat signals.Therefore, the purpose of this work was to develop a slice-by-slice shimming method based on knowledge of the water/fat distributions and B0 field map, and to evaluate this method in phantoms and volunteers.

Materials and Methods

Phantom: We scanned a simple phantom comprised of a thin layer of peanut oil resting on a larger volume of water. A surgical implant was placed near the phantom to induce substantial B0 inhomogeneities.Subjects: We scanned 5 healthy volunteers (3 male/2 female) with IRB approval and informed written consent.

MRI acquisition: Each subject was scanned (3T, GE Signa Premier), including axial DWI and 2D CSE scans of the upper leg and abdomen. Abdominal scans required respiratory triggering (DWI) or a single breath-hold (CSE). Acquired series included four co-localized 2D multi-slice acquisitions: a conventional volumetrically shimmed DWI, a DWI with zero shims, a 2D CSE scan, and an optimized-shim DWI. DWI parameters included: 6mm slice thickness; 10-16mm spacing to obtain substantial S/I coverage; 15 slices; 4 repetitions; diffusion b-values = 100 s/mm2 and 500 s/mm2. The DWI scans included spatial-spectral excitation for water excitation/fat suppression. CSE parameters included: 128×128 matrix size, TR=7.6ms, TE1=1.0ms, dTE=1.0ms, 6 echoes. From the CSE acquisition we obtained co-localized fat-only and water-only images, B0 field maps, and R2* maps.

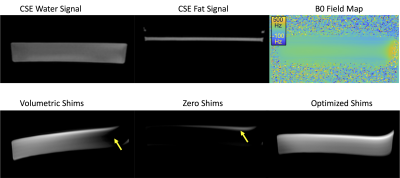

Optimization of slice-specific shim values: With slice-specific knowledge of the fat-only image, water-only image, and B0 field maps, our approach predicts the excited water and fat signals throughout the field of view and optimizes three “shim” parameters (the X/Y shim values and center frequency) at each slice (Figure 1). Based on the known spectral selectivity profile of the DWI excitation, the algorithm seeks the optimal combination of these three parameters to maximize water excitation and minimize fat signal excitation as described in Eq. 1,

$$\text{Equation 1.}~~~(cf',Xshim',Yshim')=\underset{cf,Xshim,Yshim}{\arg\min}\sum_{x}\sum_{y}~\lvert \sum_{p=1}^{6}~M_{fat}(x,y)~\cdot~a_{fat,p}~\cdot~I(\Delta~f_{fat,p}~+~fieldmap(x,y)~+~Xshim~\cdot~x~+~Yshim~\cdot~y~-~cf)\lvert^{2}~\\-~\lvert M_{water}(x,y)~\cdot~I(fieldmap(x,y)~+~Xshim~\cdot~x~+~Yshim~\cdot~y~-~cf)\lvert^{2}$$

where $$$p$$$ is one of the six fat peak resonances with relative amplitude $$$a_{fat,p}$$$ and frequency offset $$$\Delta~f_{fat,p}$$$, center frequency $$$cf$$$, magnetization $$$M$$$, and excitation intensity $$$I$$$ based on the signal's off-resonance and the known excitation spectral profile. A push-button script for fully automated CSE-based mapping of water, fat, and field map, and shim optimization was implemented and used on all exams.

Reader evaluation: Additionally, a radiologist (RVDH) specialized in musculoskeletal imaging performed a side-by-side comparison of volumetric, zeroed, and optimized shim acquisition images in the leg across all volunteers in a blinded randomized order.

Results

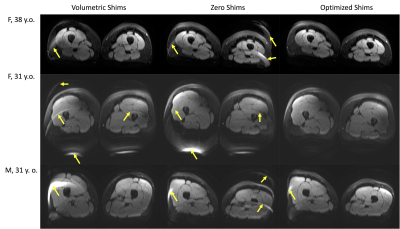

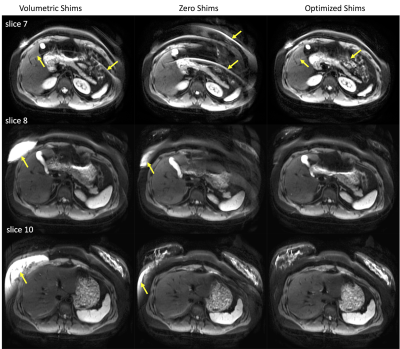

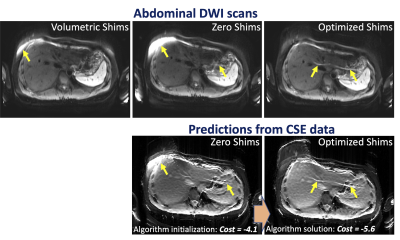

Phantom scans with optimized shims showed decreases in the number and severity of fat suppression failures (Figure 2). Data from the 5 volunteers was successfully retrieved and analyzed with no major artifacts. Upper leg scans regularly demonstrated large fat suppression failures in multiple slices of volumetrically-shimmed DWI scans. These artifacts were minimized using CSE-based slice-specific dynamic shimming optimization (Figure 3). Similarly, performance improvements were observed in the abdomen (Figure 4). Figure 5 shows a failure mode of the proposed method, where low-energy fat signals overlap desired abdominal regions.The radiologist preferred the optimized shim acquisition images for all 5 volunteers and cited reduced number and intensity of fat suppression failure artifacts and better muscle signal retention as key factors in image improvement.

Discussion

This work has demonstrated the potential to leverage CSE-based information to optimize shimming in extra-cranial DWI, where fat suppression failures due to B0 inhomogeneity currently remain a frequent source of major artifacts.In a complicated B0 environment where linear shims may not be enough to homogenize the B0 field over the entire slice, the proposed cost function could be adapted to prioritize suppressing regions of fat that would otherwise shift into an organ of interest (Figure 5). Additionally, the proposed approach could be extended to drive additional acquisition considerations for DWI, such as the direction of the EPI readout, the type of spatial-spectral pulse, higher order shims (if available), or the use of T1-based fat suppression methods.

A limitation of this pilot study is that it relied on a low number of healthy volunteers. Future studies will focus on larger numbers of patients and will evaluate the relative contributions of the two technical components of the proposed method: slice-by-slice shimming and CSE- based shim optimization. Residual eddy currents have been considered for higher-order shimming10 and our future aims include investigating potential eddy currents induced by our method.

In conclusion, slice-specific dynamic shimming based on a CSE acquisition enables DWI with improved water excitation while avoiding unwanted fat signals.

Acknowledgements

We wish to acknowledge support from the NIH (R01EB030497) and the UW Department of Radiology. Further, we wish to acknowledge GE Healthcare who provides research support to the University of Wisconsin and support from Bracco Diagnostics who provide research support to the University of Wisconsin.References

1. Roberts, N. T., Hinshaw, L. A., Colgan, T. J., Ii, T., Hernando, D., & Reeder, S. B. (2021). B0 and B1 inhomogeneities in the liver at 1.5 T and 3.0 T. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine, 85(4), 2212–2220. https://doi.org/10.1002/mrm.28549

2. Grande, F. Del, Santini, F., Herzka, D. A., Aro, M. R., Dean, C. W., Gold, G. E., & Carrino, J. A. (2014). Fat-suppression techniques for 3-T MR imaging of the musculoskeletal system. Radiographics, 34(1), 217–233. https://doi.org/10.1148/rg.341135130

3. Haase, A., Frahm, J., Hanicke, W., & Matthaei, D. (1985). 1H NMR chemical shift selective (CHESS) imaging. Physics in Medicine and Biology, 30(4), 341–344. https://doi.org/10.1088/0031-9155/30/4/008

4. De Graaf, R. A., Brown, P. B., McIntyre, S., Rothman, D. L., & Nixon, T. W. (2003). Dynamic shim updating (DSU) for multislice signal acquisition. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine, 49(3), 409–416. https://doi.org/10.1002/mrm.10404

5. Lee, S. K., Tan, E. T., Govenkar, A., & Hancu, I. (2014). Dynamic slice-dependent shim and center frequency update in 3 T breast diffusion weighted imaging. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine, 71(5), 1813–1818. https://doi.org/10.1002/mrm.24824

6. Islam, H., Law, C. S. W., Weber, K. A., Mackey, S. C., & Glover, G. H. (2019). Dynamic per slice shimming for simultaneous brain and spinal cord fMRI. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine, 81(2), 825–838. https://doi.org/10.1002/mrm.27388

7. Metz, T. (2014). Purpose Theory I. Meaning in Life, 23, 77–97. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199599318.003.0005

8. Stockmann, J. P., & Wald, L. L. (2018). In vivo B0 field shimming methods for MRI at 7 T. NeuroImage, 168, 71–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2017.06.013

9. Meneses, B. P., & Amadon, A. (2021). A fieldmap-driven few-channel shim coil design for MRI of the human brain. Physics in Medicine and Biology, 66(1). https://doi.org/10.1088/1361-6560/abc810

10. Sengupta, S., Welch, E. B., Zhao, Y., Foxall, D., Starewicz, P., Anderson, A. W., Gore, J. C., & Avison, M. J. (2011). Dynamic B0 shimming at 7 T. Magnetic Resonance Imaging, 29(4), 483–496. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mri.2011.01.002

11. Shi, Y., Vannesjo, S. J., Miller, K. L., & Clare, S. (2018). Template-based field map prediction for rapid whole brain B0 shimming. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine, 80(1), 171– 180. https://doi.org/10.1002/mrm.27020

Figures