3403

Spatial variation of the negative BOLD response in human primary visual cortex1University of Texas Health Center at Houston, Houston, TX, United States, 2Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Quantitative Imaging, fMRI (task based), Depth-dependent BOLD, neurovascular coupling, hemodynamic response function and ultra-high-field mri

The negative hemodynamic response functions (nHRF), temporal dynamics of the negative BOLD response (NBR) evoked by a brief stimulus, have been reported as an inverted version of the corresponding positive HRF (pHRF). With a careful delineation of the nHRF from the stimulus representation (SR), we found that the nHRF adjacent to the SR was not the inverted version of the corresponding pHRF. We also characterized the nHRF with respect to the depth and found inverse proportion of the nHRF amplitudes between contralateral and ipsilateral sides, which can indicate different underlying mechanisms of the nHRF.Introduction

The negative BOLD response (NBR), the decrease in BOLD signal in regions adjacent to the positive BOLD response (PBR) and/or ipsilateral to a stimulus, has been frequently observed in BOLD fMRI experiments. The NBR and its origin have been explored intensively1-10. Functional inhibition and reduced neural activity associated with the NBR are demonstrated in human visual cortex2,6, and non-human primate visual cortex3,5. However, there is yet a dearth of understanding of temporal characteristics and spatial structure of the NBR. Here, to further understand the dynamics of the NBR, we propose to examine depth-dependent and distance-dependent variations along the cortical surface of the negative hemodynamic response function (nHRF) within gray matter.Methods

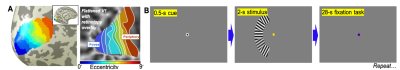

Functional data was collected using a SMS-accelerated echo-planar imaging (EPI) sequence at 7T with 0.9-mm voxel with 1.25-s TR, GRAPPA = 2, SMS = 3, and 24-ms TE. 20 quasi-coronal slices were obtained to cover the primary visual cortex. A retinotopic map was obtained for each subject in a separate session using population receptive field analysis to delineate V1, where the eccentricity gradient is clearest11 (Fig. 1A). We then subdivided these regions-of-interest (ROIs) into nine 1°-wide ROIs in eccentricity from 0—9° for each hemisphere.Our stimulus protocol consisted of a color-changing fixation dot, and a unilateral sector subdivided into five subsectors with an eccentricity of 4–6° that covers a polar angle from 220–320° (left hemifield) on a mean-gray screen (Fig. 1B). Each subsector contained a high-contrast grating that reverses contrast at 4 Hz. The main task is a challenging 2-s duration random contrast-decrement detection while maintaining fixation. Subjects then performed a non-demanding, slow-paced fixation color-detection task for the 28-s during inter-stimulus-interval. This cycle is repeated 16 times in each run, with 6 runs in each scanning session.

We also obtained a high-resolution (0.7-mm voxels) T1-weighted MP-RAGE anatomy volume, which was segmented using the high-resolution FreeSurfer approach12 to delineate gray and white matter. Using our level-set approach13, we obtain a self-reciprocal depth coordinate system which creates depth trajectories with one-to-one correspondence between vertices on the gray/white interface and the pial surface. We obtain a normalized depth index, w, which is used for depth analysis and to obtain voxels only in the middle of the gray matter (Fig. 2). Voxels with a contrast-to-noise ratio ≥ 3 within each ROI are averaged across depth bins of width 0.25 (one quarter of local gray-matter depth, mean thickness 0.58 mm) that are stepped through the gray-matter depths in increments of 0.1.

Results

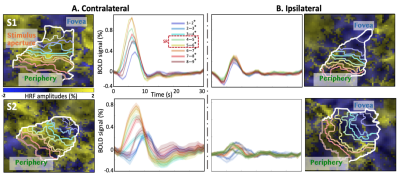

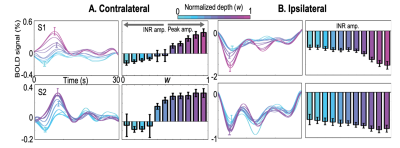

In the stimulus representation (SR), strong positive HRFs (pHRFs) in the V1 representation were observed, consistent with previous studies14,15 (Fig. 3). Outside the SR, the nHRFs in both contra- and ipsilateral V1 were not inverted versions of the pHRF and generally had lower and more delayed positive peaks away from the SR, with the initial negative response (INR) becoming more evident near the fovea and periphery. In the ipsilateral regions, INR amplitudes were weak but evident near the fovea while delayed time to peaks (TTPs) became evident near the fovea and periphery.For depth analysis, averaging over the SR, we observed a monotonic increase in peak amplitude for the pHRF as a function of depth. Averaging over ROIs near the fovea (1-3°), we observed remarkably different depth trends for the nHRF. In the contralateral side (Fig. 4A), a monotonic decrease in INR amplitude from deep to intermediate gray matter was found while a monotonic increase in positive peak amplitude was observed from intermediate to superficial gray matter without any INRs. In the ipsilateral gray matter, strong INR amplitudes were found in the most superficial gray matter (Fig. 4B); significant monotonic increase in INR amplitude from deep to superficial gray matter was observed (p <0.001).

Discussion

The depth profiles for the contra- and ipsilateral NBRs can indicate different underlying mechanisms, which has not been reported previously. However, considering that stable TTI was observed for all nHRFs throughout depth across all subjects, contra- and ipsilateral NBR are tightly coupled with each other as well as with the corresponding PBR.Acknowledgements

Work was supported by NIH NINDS R01 NS121040 and NINDS R56NS095933. We thank Natasha De La Rosa and David Wang for their thoughtful advice and help.References

1. Mullinger KJ, Mayhew SD, Bagshaw AP, et al. Evidence that the negative BOLD response is neuronal in origin: a simultaneous EEG–BOLD–CBF study in humans. Neuroimage 2014; 94: 263-274.

2. Shmuel A, Yacoub E, Pfeuffer J, et al. Sustained negative BOLD, blood flow and oxygen consumption response and its coupling to the positive response in the human brain. Neuron 2002; 36: 1195-1210.

3. Shmuel A, Augath M, Oeltermann A, et al. Negative functional MRI response correlates with decreases in neuronal activity in monkey visual area V1. Nature Neuroscience 2006; 9: 569.

4. Kastrup A, Baudewig J, Schnaudigel S, et al. Behavioral correlates of negative BOLD signal changes in the primary somatosensory cortex. Neuroimage 2008; 41: 1364-1371.

5. Goense J, Merkle H and Logothetis NK. High-resolution fMRI reveals laminar differences in neurovascular coupling between positive and negative BOLD responses. Neuron 2012; 76: 629-639.

6. Pasley BN, Inglis BA and Freeman RD. Analysis of oxygen metabolism implies a neural origin for the negative BOLD response in human visual cortex. Neuroimage 2007; 36: 269-276.

7. Stefanovic B, Warnking JM and Pike GB. Hemodynamic and metabolic responses to neuronal inhibition. Neuroimage 2004; 22: 771-778.

8. Havlicek M, Ivanov D, Roebroeck A, et al. Determining excitatory and inhibitory neuronal activity from multimodal fMRI data using a generative hemodynamic model. Frontiers in Neuroscience 2017; 11: 616.

9. Huber L, Goense J, Kennerley AJ, et al. Investigation of the neurovascular coupling in positive and negative BOLD responses in human brain at 7 T. Neuroimage 2014; 97: 349-362.

10. Smith AT, Williams AL and Singh KD. Negative BOLD in the visual cortex: evidence against blood stealing. Human Brain Mapping 2004; 21: 213-220.

11. Greene CA, Dumoulin SO, Harvey BM, et al. Measurement of population receptive fields in human early visual cortex using back-projection tomography. Journal of Vision 2014; 14: 17.

12. Zaretskaya N, Fischl B, Reuter M, et al. Advantages of cortical surface reconstruction using submillimeter 7 T MEMPRAGE. NeuroImage 2018; 165: 11-26.

13. Khan R, Zhang Q, Darayan S, et al. Surface-based analysis methods for high-resolution functional magnetic resonance imaging. Graphical Models 2011; 73: 313-322.

14. Kim JH and Ress D. Reliability of the depth-dependent high-resolution BOLD hemodynamic response in human visual cortex and vicinity. Magn Reson Imaging 2017; 39: 53-63. 2017/02/01.

15. Polimeni JR, Fischl B, Greve DN, et al. Laminar analysis of 7 T BOLD using an imposed spatial activation pattern in human V1. Neuroimage 2010; 52: 1334-1346.

Figures

Fig. 2: Left) Normalized distance map (w) on coronal plane. Right) morphing a brain. The depth-mapping scheme smoothly transitions from the gray/white matter interface to the pial surface.