3355

Time dependent diffusion and kurtosis of human brain metabolites1Cardiff University Brain Research Imaging Centre (CUBRIC), School of Psychology, Cardiff University, Cardiff, United Kingdom, 2Department of Mathematics, University of Bern, Bern, Switzerland, 3School of Computer Science and Informatics, Cardiff University, Cardiff, United Kingdom, 4Leeds Institute of Cardiovascular and Metabolic Medicine, University of Leeds, Leeds, United Kingdom, 5Magnetic Resonance Methodology, Institute of Diagnostic and Interventional Neuroradiology, University Bern, Bern, Switzerland, 6Translational Imaging Center, sitem-insel, Bern, Switzerland, 7Université Paris-Saclay, CEA, CNRS, MIRCen, Laboratoire des Maladies Neurodégénératives, Fontenay-aux-Roses, Paris, France

Synopsis

Keywords: Gray Matter, Spectroscopy, Metabolites, Diffusion, ADC, Kurtosis, Morphology, Gray Matter, Spectroscopy

This work demonstrates that metabolites diffusion and kurtosis time-dependence can be measured in vivo in the human brain using Diffusion-Weighted MR Spectroscopy (DW-MRS) and ultra-strong gradients. At short diffusion-times, DW-MRS is sensitive to cytoplasmic viscosity and short-range structures; at long diffusion-times to long-range structures. We show that modeling the diffusion-time dependence of intracellular and cell-type specific metabolites can be used to infer brain cell morphology and recover fiber radii consistent with healthy human brain histology. Furthermore, we show that water diffusion at long diffusion-times is affected by exchange between intra- and extracellular compartment, which poses challenges for microstructural modeling.Introduction

Metabolites are intracellular and cell-type specific (NAA [neuronal], Cho and mI [glial]) and by measuring their diffusion-time (TD) dependence one can infer brain tissue structural disorder[1] and restrictions[2]–[5]. More recently, brain metabolites apparent diffusion [ADC(TD)] and Kurtosis [K(TD)] TD dependence has been measured up to 500ms in the mouse brain showing promising results as a potential biomarker for brain cell morphology[6]. Here, we provide first evidence that DW-MRS can provide metabolite ADC(TD) and K(TD) in the human brain from short (6ms) to long (250ms) TDs.Methods

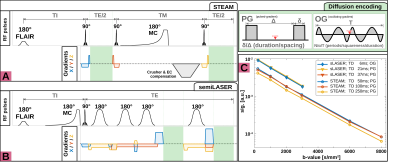

Data acquisition: Measurements were conducted on a 3T Connectom-A MR scanner (Siemens Healthcare) with 300mT/m per axis with a 32-channel receive headcoil. Voxel positioning and tissue segmentation used 1mm3 isotropic MPRAGE images. Brain metabolite diffusion was measured at: (i) short to intermediate TDs (6, 21, 37ms) with semiLASER[5] (TE/TR: 76/3000ms; b: 200, 1000, 2000, 3000s/mm2; Gmax: 254mT/m, Fig.1A) using oscillating and pulsed gradient diffusion encoding and (ii) intermediate to long TDs (50, 100, 250ms) with STEAM[7] (TE/TR: 37/3000ms; b: 200, 1000, 2000, 3000, 6000, 8000s/mm2; Gmax: 151mT/m, Fig.1B) using pulsed gradient diffusion encoding. Diffusion encoding was applied with equal gradient strength along x/y, but not z to minimize table vibrations. For b<3000s/mm2 32 transients were acquired and 64 otherwise. FLAIR was used for CSF suppression and metabolite-cycling to measure water and metabolite diffusion simultaneously. Cross-terms were compensated by diffusion-gradient polarity inversion. Sequences were validated in a NIST phantom[8] with free Gaussian diffusion(Fig.1C). A macromolecular baseline (MMBG) was acquired for STEAM at all TDs using metabolite nulling (inversion time: 765ms) and moderate diffusion-weighting (5000s/mm2).Data processing: The inherent water reference was used for coil-channel combination, phase-offset, frequency-drift and eddy-current correction and motion compensation to restore signal amplitudes to a reference level presumably unaffected by motion[9].

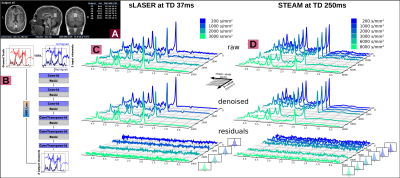

Subjects: Six healthy subjects (33.1±2.3yrs, 4 female) were measured with the VOI (9.6±1.5mL) in posterior cingulate cortex (Fig.2A).

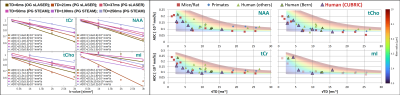

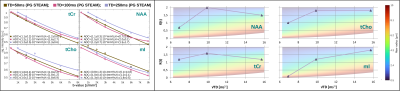

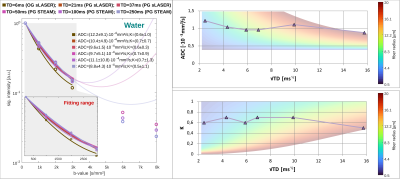

Analysis, Fitting and Modeling: An autoencoder network[11] was trained for denoising (Fig.2B). The cohort average was calculated for each TD using the inverse variance of the inherent water references as weights to mitigate signal loss from remaining subject motion. Metabolic basis-sets for Asp, tCr, GABA, Glc, Gln, Glu, Gly, tCho, GSH, mI, Lac, NAA, NAAG, PE, sI and Tau were simulated with MARSS[10] considering RF pulse profiles and sequence chronograms. Basis-sets and MMBG were imported into FiTAID[12] for sequential linear-combination modeling. Two diffusion representation models were implemented in MatLab to fit TD dependence of: (i) ADC(TD) alone at low b-values (≤3000s/mm2), and (ii) ADC(TD) and K(TD) for the full b-value range. A fully dispersed cylinder model was used to infer the dependence of the fiber radius on ADC(TD) and K(TD) (assuming D0=3∙ADC∞≈3∙ADC(250ms), i.e. D0,metab=0.3∙10-3mm2/s, D0,water=3.0∙10-3mm2/s, cf. Fig.3&5).

Results and Discussion

Metabolite ADC(TD): Metabolite ADCs are highest for TDs<21ms and plateauing at TDs>50ms (Fig.3). The higher ADCs found in the kurtosis model (Fig.4) indicate contribution from non-Gaussian diffusion even for b<3000s/mm2. The ADCs at ultra-short TD of 6ms measured with oscillating gradients had higher uncertainties for tCho and mI, probably related to stronger eddy-currents due to high diffusion-gradient amplitudes. The ADC(TD) dependence is in-line with fiber radii between 0.5-4.0μm(Fig.3).Metabolite K(TD): The K(TD) of the major brain metabolites increase with TD (Fig.4), in agreement with results in mice[6]. This hints at larger interactions with cellular boundaries at TDs>50ms responsible for non-Gaussian diffusion. Fiber radii obtained from K(TD) range from 0.5-4.0μm and agree with the results from ADC(TD) (except for mI at TD=50ms).

Water ADC(TD) and K(TD): The ADC(TD) of water overall increases towards shorter TD, while K(TD) shows little to absent TD dependence (Fig.5). The possible fiber radii are TD dependent and range from 0.5-10μm for TD<50ms to 10-20μm for TD>50ms.

Denoising: Though a Gaussian noise characteristic indicates a bias free performance of the denoising (Fig.2&D) only modest improvements of 6% for confidence intervals for ADC(TD) and K(TD) were found.

Conclusion

The elevated metabolite ADCs at short TDs indicate a shift in compartmental sensitivity towards smaller cellular structures and cytoplasmic viscosity, while the non-zero plateau at long TD underpins the hypothesis of metabolite diffusion rather in long branched cylinders than small restricting organelles. Though the model of fully dispersed cylinders might be an oversimplification it reproduces fiber radii from histology for metabolite diffusion. In contrast, water diffusion only yields reasonable results for TD<50ms, which points at significant effects from water exchange at longer TD. This is supported by the steady loss in signal for TDs>50ms at high b-values, the non-zero kurtosis at the longest TD and agrees with diffusion-weighted MRI studies of water exchange[13],[14]. It is important to note that these are preliminary results and validation in a larger sample size is needed.Although reported in one recent animal study[6], metabolites ADC(TD) and K(TD) have remained uninvestigated in the human brain. Here, we demonstrated -by exploiting state-of-the-art DW-MRS and ultra-strong gradients- that it is possible to measure metabolite ADC(TD) and K(TD) in vivo in the human brain.

Acknowledgements

AD is supported by a Swiss National Science Foundation Fellowship (SNSF #202962). MA is supported by a Wellcome Trust Investigator Award (219536/Z/19/Z). MP, KS are supported by a UKRI Future Leaders Fellowship (MR/T020296/2). DKJ is supported by a Wellcome Trust Strategic Award (104943/Z/14/Z).References

[1] Novikov DS, Jensen JH, Helpern JA, Fieremans E. Revealing mesoscopic structural universality with diffusion. Proc Natl Acad Sci 2014, 111:5088-93.

[2] Palombo M, Ligneul C, Najac C, Le Douce J, Flament J, Escartin C, Hantraye P, Brouillet E, Bonvento G, Valette J. New paradigm to assess brain cell morphology by diffusion-weighted MR spectroscopy in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci 2016, 113:6671-6.

[3] Ligneul C, Valette J. Probing metabolite diffusion at ultra-short time scales in the mouse brain using optimized oscillating gradients and short-echo-time diffusion-weighted MRS. NMR Biomed 2017, 30:e3671.

[4] Valette J, Ligneul C, Marchadour C, Najac C, Palombo M. Brain Metabolite Diffusion from Ultra-Short to Ultra-Long Time Scales: What Do We Learn, Where Should We Go?. Front Neurosci 2018, 12:1-6.

[5] Döring A, Kreis R. Magnetic resonance spectroscopy extended by oscillating diffusion gradients: Cell-specific anomalous diffusion as a probe for tissue microstructure in human brain. Neuroimage 2019, 202: 116075.

[6] Mougel E, Valette J, Palombo M. Investigating exchange, structural disorder and restriction in Gray Matter via water and metabolites diffusivity and kurtosis time-dependence. Int Soc Mag Reson Med 2022, 255.

[7] Brandejsky V, Boesch C, Kreis R. Proton diffusion tensor spectroscopy of metabolites in human muscle in vivo. Magn Reson Med 2015, 73:481-7.

[8] Palacios EM, Martin AJ, Boss MA, Ezekiel F, Chang YS, Yuh EL, Vassar MJ, Schnyer DM, MacDonald CL, Crawford KL, Irimia A, Toga AW, Mukherjee P. Toward Precision and Reproducibility of Diffusion Tensor Imaging: A Multicenter Diffusion Phantom and Traveling Volunteer Study. Am J Neuroradiol 2017, 38:537-45.

[9] Döring A, Adalid V, Boeschj C, Kreis R. Diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance spectroscopy boosted by simultaneously acquired water reference signals. Magn Reson Med 2018, 80:2326-38.

[10] Landheer K, Swanberg KM, Juchem C. Magnetic resonance Spectrum simulator (MARSS), a novel software package for fast and computationally efficient basis set simulation. NMR Biomed 2019, 34: e4129.

[11] Rösler F, Döring A. MRspecNET. 2022. https://github.com/frank-roesler/MRspecNET

[12] Adalid V, Döring A, Kyathanahally SP, Bolliger CS, Boesch C, Kreis R. Fitting interrelated datasets: metabolite diffusion and general lineshapes. Magn Reson Mater Physics 2017, 30:429-448.

[13] Olesen JL, Østergaard L, Shemesh N, Jespersen N. Diffusion time dependence, power-law scaling, and exchange in gray matter. Neuroimage 2022, 251: 118976.

[14] Jelescu IO, de Skowronski A, Geffroy F, Palombo M, Novikov DS. Neurite Exchange Imaging (NEXI): A minimal model of diffusion in gray matter with inter-compartment water exchange. Neuroimage 2022, 256: 119277.

Figures