3345

Alterations of static and dynamic functional connectivity in adolescents with first-episode major depression and suicidal tendencies1The Affiliated Brain Hospital of Guangzhou Medical University, Guangzhou, China, 2South China University of Technology, Guangzhou, China, 3Guangzhou Integrated Traditional Chinese and Western Medicine, Guangzhou, China, 4Philips Healthcare, Guangzhou, China

Synopsis

Keywords: Brain Connectivity, Adolescents, major depressive disorder; suicide; FCS

This study used graph theory-based dynamic and static functional connectivity strength (FCS) approaches to investigate the differences in global brain connectivity patterns in depressed adolescents with and without suicide attempts. Our findings suggest that abnormal connectivity patterns in multiple brain regions involving cognition and emotion control, and self-referential processing are associated with the increasing risk of vulnerability to a suicide attempt in depressed adolescents.Background

A growing body of evidence showed that corticostriatolimic system dysfunctions were linked to suicide behaviors in individuals with major depressive disorder MDD)[1]. However, the neurobiological mechanism that makes depressed youths more vulnerable to suicide is poorly understood[2]. Therefore, this study aimed to investigate the functional connectivity pattern in depressed adolescents with prior suicide attempts.Methods

A total of 115 depressed adolescents with and without prior suicide attempts (SA) and 35 age-, education-, and gender-matched healthy controls underwent resting-state functional imaging (R-fMRI) scans. The dynamic FCS (dFCS) variability and static FCS (sFCS) metrics were measured.Results

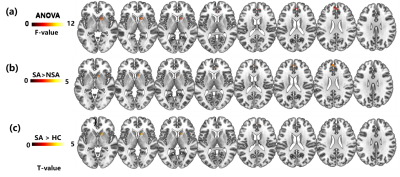

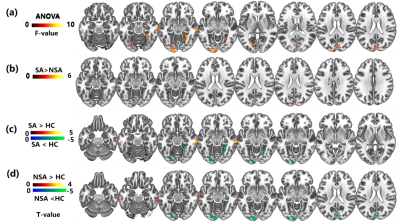

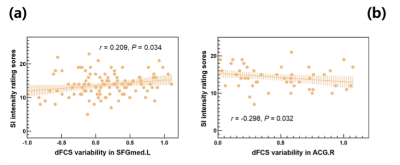

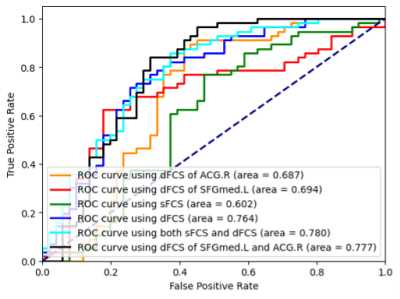

We found that the dFCS variability of the major depressive disorder with suicide attempts (MDD-SA) group was higher than that of the major depressive disorder without suicide attempts (MDD-NSA) group in the right caudate nucleus/pallidum, right anterior cingulate gyrus and left medial superior frontal gyrus (Figure 1), and the MDD-SA group showed higher sFCS values in the bilateral cuneus (Figure 2). dFCS variability of the left medial superior frontal gyrus and right anterior cingulate gyrus was significantly correlated with the SI intensity rating scores (Figure 3). Combining the altered dFCS and sFCS metrics could improve the classification performance for discriminating MDD-SA from MDD-NSA (area under the curve: 0.780) (Figure 4).Discussion

The caudate nucleus and lentiform nucleus are important components of the striatum and core nodes of the reward network that are linked to decision-making and reinforcement learning[1]. Lower caudate and putamen volumes have been reported in depressed adults with suicide attempters in comparison to non-attempters[2]. As one of the core nodes of the default network, the medial prefrontal lobe has been proven to play an important role in introspection, evaluation of internal positive and negative emotions, and evaluation of future imaginary events[3]. Just et al.[4] used the machine learning method to explore the neural representation of suicidal behavior in adolescents, and the results suggested that the multivariable pattern of fMRI activation and response generated by the medial superior frontal gyrus was the most discriminative neural representation when actively thinking about concepts related to life and death. Taken together, we speculated that the disturbances of the functional connectome in the striatum and medial prefrontal lobe may contribute to impaired decision-making self-referential processing, thus leading to an increased risk of suicidal behaviors.Conclusions

Our findings suggest that abnormal connectivity patterns in multiple brain regions involving cognition and emotion control, and self-referential processing are associated with the increasing risk of vulnerability to a suicide attempt in depressed adolescents. Furthermore, FCS could serve as a sensitive biomarker for revealing the neurobiological mechanisms underlying suicidal vulnerability.Acknowledgements

This research was supported in part by the National Natural Science Foundation of China [81771466]; the Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province, China [2021A1515011288]; Science and Technology Program of Guangzhou [202102010020]; High-tech and Major Featured Project of Guangzhou [2019TS46]; Health Science and Technology Project of Guangzhou [20211A010037]; Science and Technology Program of Guangzhou, China [202102080665].References

[1] BRACHT T, LINDEN D, KEEDWELL P. A review of white matter microstructure alterations of pathways of the reward circuit in depression [J]. J Affect Disord, 2015, 187: 45-53.

[2] SCHMAAL L, VAN HARMELEN A L, CHATZI V, et al. Imaging suicidal thoughts and behaviors: a comprehensive review of 2 decades of neuroimaging studies [J]. Mol Psychiatry, 2020, 25(2): 408-27.

[3] MULLER N C J, DRESLER M, JANZEN G, et al. Medial prefrontal decoupling from the default mode network benefits memory [J]. Neuroimage, 2020, 210: 116543.

[4] JUST M A, PAN L, CHERKASSKY V L, et al. Machine learning of neural representations of suicide and emotion concepts identifies suicidal youth [J]. Nat Hum Behav, 2017, 1: 911-9.

Figures