3343

Functional magnetic resonance imaging reveals fidgeting in ADHD improves prefrontal cortex activation during executive functioning1Auckland Bioengineering Institute, University of Auckland, Auckland, New Zealand, 2Mātai Medical Research Institute, Tairāwhiti/Gisborne, New Zealand, 3General Electric Healthcare AUS/NZ, Melbourne, Australia, 4Centre for Brain Research, University of Auckland, Auckland, New Zealand, 5Department of Anatomy and Medical Imaging, Faculty of Medical and Health Sciences, University of Auckland, Auckland, New Zealand, 6Department of Psychology, Faculty of Science, University of Auckland, Auckland, New Zealand, 7Ngai Tāmanuhiri, Rongowhakaata, Ngāti Porou, Tūranganui-a-Kiwa, Tairāwhiti, New Zealand, 8Department of Engineering Science, Faculty of Engineering, University of Auckland, Auckland, New Zealand

Synopsis

Keywords: Brain Connectivity, fMRI (task based), ADHD, fidgeting MRI

People with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) are often observed to fidget or display repetitive fine motor skills. Though it has been proposed that fidgeting may assist with concentration and sustained attention, there is little objective evidence to support this idea. This is the first study to evaluate the impact of fidgeting, using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), with neurotypical and ADHD adult volunteers. Comparative analyses revealed significant increases in medial prefrontal cortex brain activation while fidgeting during executive functioning in the ADHD participant. This distinction may provide additional information in future MRI diagnosis of ADHD.

Introduction

A diagnosis of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) is typically established using a combination of several psychological assessments and occasionally surface electrophysiological mapping1. Recently, MRI studies have shown the very real potential to establish useful ADHD biomarkers2,3. However, one clinical characteristic of ADHD that has yet to be explored using fMRI is fidgeting4. In this pilot study, we investigated the potential for using fMRI integrated with a functional cognitive task to identify if fidgeting behaviour might modify medial prefrontal cortex activation.Methods

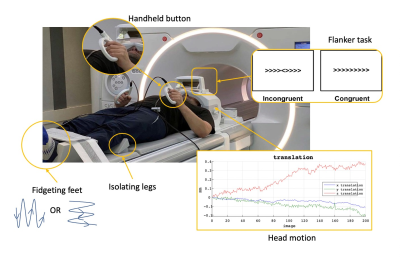

Ethical approval was received from the New Zealand Health and Disability Ethics Committee. Figure 1 shows the MRI setup using a 3T (GE Discovery Signa Premier) with a AIR™ 48-channel head coil. The lower limb was isolated with knee supports to prevent motion artifacts from influencing the head coil. Data collected when motion artifacts exceeded 3mm were removed from processing. Two volunteers (one diagnosed with ADHD and one neurotypical) participated in this pilot study. A fMRI sequence was used to evaluate the impact of fidgeting while performing an executive functioning assessment called the Flanker task5. The Flanker task consisted of each volunteer being asked to identify the direction of a central arrow symbol (using a clicking device) in an array of arrows. The default mode network (DMN) activations were contrasted using the standard network atlas of Yeo et al. (2011)6 in the CONN toolbox7.Results

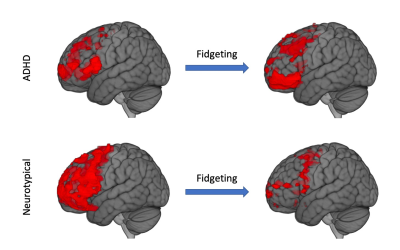

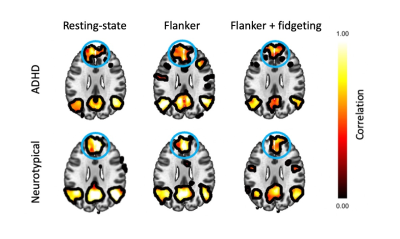

Activation in the frontal lobe increased significantly by 45% in the ADHD participant while fidgeting and performing the Flanker task (Figure 2). In contrast, the neurotypical participant showed an 82% decline in activation in the same region while fidgeting and performing the Flanker task. Considering only the medial prefrontal cortex, activation increased by 94% in the ADHD participant while fidgeting and performing the Flanker task. In contrast, the neurotypical participant showed a decline of 82% in activation again under the same conditions.The ADHD participant showed a strong correlation between activity in the medial prefrontal cortex (circled area in Figure 3) and the DMN during the Flanker task. Importantly, the ADHD volunteer's ability to shift away from the DMN during the Flanker task only improved while fidgeting. In contrast, the neurotypical volunteer easily shifted from the DMN when performing the Flanker task without the need to fidget (Figure 3).

Discussion

This pilot study showed that increased activation in the prefrontal cortex is associated with fidgeting activity in ADHD. This suggests that fidgeting and fine repetitive motor skills might aid concentration and sustained attention for those with ADHD. As expected, we also observed that the sensorimotor network associated with motor skills was activated while fidgeting. Interestingly, in the neurotypical participant, Flanker performance was hindered by fidgeting, and activation was reduced in the medial prefrontal cortex. This suggests that fidgeting might be a learned adaptive behaviour in the ADHD brain to improve higher executive functioning, whereas fidgeting might distract neurotypical participants and be perceived as a secondary loading task when it is not natural for them.Secondly, it was observed that fidgeting aids those with ADHD shift from the DMN during Flanker performance. Though it is known that those with ADHD have trouble transitioning from the DMN8,9, this is the first empirical MRI evidence that fidgeting activity assists this transition. Specifically, the medial prefrontal cortex, which is associated with higher executive functioning10,11, is most assisted by fidgeting in ADHD during executive functioning tasks, while the neurotypical case could shift from the DMN easily without fidgeting.

Conclusion

This study has revealed, for the first time, that fidgeting, may assist executive functioning in ADHD by increasing activation in the prefrontal cortex. This may assist those with ADHD shift from the DMN to other task-positive brain networks and offer clinicians an alternative to current medical interventions.Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge support from the Mātai Medical Research Institute and funding from the University of Auckland Ideation Grant awarded to J. Fernandez. Our team acknowledges the participants, especially those from Tairāwhiti-Gisborne, without whom this study would not be possible. We are also grateful to Mātai Ngā Māngai Māori for their guidance toward this study, and GE Healthcare.

References

1. Snyder, S. M., Rugino, T. A., Hornig, M. & Stein, M. A. Integration of an EEG biomarker with a clinician’s ADHD evaluation. Brain Behav 5, 1–17 (2015).

2. Albajara Sáenz, A., Villemonteix, T. & Massat, I. Structural and functional neuroimaging in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Dev Med Child Neurol 61, 399–405 (2019).

3. Bush, G., Valera, E. M. & Seidman, L. J. Functional neuroimaging of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: A review and suggested future directions. Biological Psychiatry vol. 57 1273–1284 Preprint at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.01.034 (2005).

4. Gawrilow, C., Kühnhausen, J., Schmid, J. & Stadler, G. Hyperactivity and motoric activity in ADHD: Characterization, assessment, and intervention. Front Psychiatry 5, 1–10 (2014).

5. Eriksen, B. & Eriksen, C. W. Effects of noise letters upon the identification of a target letter in a nonsearch task*. Perception & Psychophysics vol. 16 (1974).

6. Thomas Yeo, B. T. et al. The organization of the human cerebral cortex estimated by intrinsic functional connectivity. J Neurophysiol 106, 1125–1165 (2011).

7. Whitfield-Gabrieli, S. & Nieto-Castanon, A. Conn: A Functional Connectivity Toolbox for Correlated and Anticorrelated Brain Networks. Brain Connect 2, 125–141 (2012).

8. Querne, L. et al. Effects of Methylphenidate on Default-Mode Network/Task-Positive Network Synchronization in Children With ADHD. J Atten Disord 21, 1208–1220 (2017).

9. Christakou, A. et al. Disorder-specific functional abnormalities during sustained attention in youth with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder ( ADHD ) and with Autism. Mol Psychiatry 236–244 (2013) doi:10.1038/mp.2011.185.

10. Alexander, W. H. & Brown, J. W. Medial prefrontal cortex as an action-outcome predictor. Nat Neurosci 14, 1338–1344 (2011).

11. Euston, D. R., Gruber, A. J. & McNaughton, B. L. The Role of Medial Prefrontal Cortex in Memory and Decision Making. Neuron vol. 76 1057–1070 Preprint at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2012.12.002 (2012).

Figures

Figure 1: MRI setup for Flanker task and fidgeting measurement.

Figure 2: Brain activation (RED) for ADHD and neurotypical participants with and without fidgeting.

Figure 3: Default mode network (DMN) correlation maps for ADHD and neurotypical participants showing resting, Flanker task, and Flanker+fidgeting. The circled area is the medial prefrontal cortex seed point.