3335

Brain connectivity markers for the diagnosis of non-suicidal self-injury in adolescents: a DTI and resting-state fMRI study1West China Hospital, Sichuan University, Chengdu, China, 2Central Research Institute, United Imaging Healthcare, Shanghai, China

Synopsis

Keywords: Brain Connectivity, Psychiatric Disorders, Non-suicidal self-injury

Non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI), defined as the deliberate damage or destruction of body tissue without the intent to die, is a common behavior amongst adolescents. We conducted connectome-based analysis to investigate neural correlates of self-injury and identified several potential brain connectivity markers of NSSI diagnosis. On basis of these markers, the random forest model achieved an accuracy of 78.2% to discriminate between NSSI and non-NSSI patients. Our study indicated that structural and functional connectivity could characterize the behavior of self-injury and help early NSSI diagnosis in adolescents.Introduction

Non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI), defined as the deliberate damage or destruction of body tissue without the intent to die, is a common behavior amongst adolescents1,2. Despite multiple negative sequalae of NSSI, including disruptions in interpersonal relationships and increased risk for problem behaviors including substance use, violence towards others, and suicidal attempts and deaths by suicide3, there are only a small number of studies that address neural correlates of NSSI early in the course of these behaviors. Studies examining these correlates early in the course of NSSI may provide valuable data on processes that help distinguish between risk factors and correlates of NSSI. Moreover, early NSSI diagnosis may allow individual intervening treatment in advance, based on the identification of brain abnormalities underlying these behaviors. This study is to investigate brain connectivity markers of NSSI in adolescents, using diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) and resting-state functional MRI (rs-fMRI).Methods

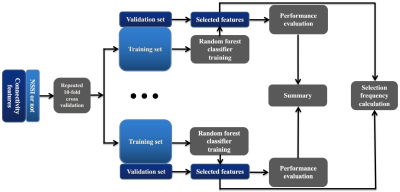

We retrospectively evaluated 89 NSSI patients (self-injury frequency >= 5), 45 non-NSSI patients (self-injury frequency < 5) and 40 healthy control subjects (HC) who underwent a DTI and rs-fMRI scanning in a 3.0 Tesla MRI system (uMR 790, United Imaging Healthcare, Shanghai, China). The preprocessing of DTI data was performed using the toolbox of PANDA4 in MATLAB (MathWorks). It consisted of skull removal and cropping the gap, correcting motion and eddy current distortions, calculating diffusion tensors. The rs-fMRI data was preprocessed in FSL5. The main steps included brain extraction, slice timing correction, rigid-body motion correction, spatial smoothing using a Gaussian kernel of FWHM of 6 mm, and high-pass temporal filtering of 150 s. According to the Brainnetome atlas that parcellates the brain into 210 cortical and 36 subcortical sub-regions6, ROI-based structural and functional connectivity analysis was employed to extract 60270 connectivity features from preprocessed DTI and rs-fMRI data. Then the extracted features were put into an all-relevant feature selection procedure within cross-validation loops to identify features with significant discriminative power for patient classification (Figure 1). Permutation test (permuted 1000 times) was applied to identify the features with significantly higher selection frequency than random values as NSSI-related selections. And the statistical result was corrected for multiple comparisons using the false discovery rate (FDR) method for the corresponding p value.Results

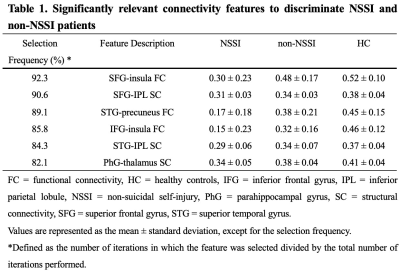

When the self-injury frequency is larger than five days per year, the adolescent can be diagnosed to have NSSI. According to this criterion, all patients were divided into NSSI (n = 89) and non-NSSI (n = 45) groups. There were no significant differences in age, gender and education between patients and HCs, and also between NSSI and non-NSSI patients, using a chi-squared test for gender and two-tailed t-tests for continuous variables (all p values > 0.1). Six connectivity features were identified to be significantly relevant to patient classification by permutation test (all p values < 0.001), which was summarized in Table 1. They all showed significant differences between NSSI and non-NSSI, also between NSSI and HC (all p values < 0.01). On basis of these relevant features, the accuracy of the random forest models was 78.2% as well as a specificity of 75.9% and a sensitivity of 83.1%, in discriminating NSSI and non-NSSI.Discussion & Conclusion

In brief, our study indicated that structural and functional connectivity could characterize the behavior of self-injury and help early NSSI diagnosis in adolescents. Using the all-relevant feature selection procedure, we identified six connectivity markers of self-injury. On basis of these markers, the random forest model achieved an accuracy of 78.2% to discriminate between NSSI and non-NSSI patients.In this study, we focused on the behavior of self-injury in adolescents. When the self-injury frequency is larger than five days per year, the adolescent can be diagnosed to have NSSI. According to this criterion, all patients were divided into NSSI and non-NSSI groups. We extracted features of whole-brain structural and functional connectivity from a considerable number of patients. Connectivity features were put into an all-relevant feature selection procedure. Compared with the commonly used methods such as t-test and Pearson’s correlation analysis to select related features and primary component analysis to reduce the dimensionality of feature space, the all-relevant feature selection algorithm can identify all features that significantly contribute to classification in a data-driven manner. Moreover, there were no significant differences in patients’ age, sex and education between NSSI and non-NSSI groups. Thus, it was valid to identify brain connectivity markers of self-injury through the mentioned analyses. On the basis of identified markers, our random forest classifiers achieved the mean accuracy of 78.2% to discriminate between patients with and without NSSI. The classifiers were derived from patients’ DTI and rs-fMRI data without performing any specific task, which revealed its potential clinical value for NSSI diagnosis in adolescents.

In conclusion, we found an abnormal pattern of structural and functional connectivity in NSSI comparing to non-NSSI and HC, which independently contributed to patient subtyping. The brain connectivity markers might provide possible brain pathological mechanism in NSSI patients for precision medicine.

Acknowledgements

NoneReferences

1. Muehlenkamp JJ, Claes L, Havertape L, Plener PL. International prevalence of adolescent non-suicidal self-injury and deliberate self-harm. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health. 2012;6:10.

2. Swannell SV, Martin GE, Page A, Hasking P, St John NJ. Prevalence of nonsuicidal self-injury in nonclinical samples: systematic review, meta-analysis and meta-regression. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2014;44(3):273-303.

3. Kleiman EM, Ammerman BA, Kulper DA, Uyeji LL, Jenkins AL, McCloskey MS. Forms of non-suicidal self-injury as a function of trait aggression. Compr Psychiatry. 2015;59:21-7.

4. Cui Z, Zhong S, Xu P, He Y, Gong G. PANDA: a pipeline toolbox for analyzing brain diffusion images. Front Hum Neurosci. 2013;7:42.

5. Jenkinson M, Beckmann CF, Behrens TE, Woolrich MW, Smith SM. FSL. Neuroimage. 2012;62:782-790.

6. Fan L, Li H, Zhuo J et al. The human Brainnetome Atlas: a new brain atlas based on connectional architecture. Cereb Cortex. 2016;26:3508-3526.