3318

Hyperactive BOLD response in presymptomatic AD mice model as potential biomarker of early AD

Taeyi You1,2, Taekwan Lee3, Geun Ho Im1, Seong-gi Kim1, Sungkwon Chung4, and Jung Hee Lee5

1Center for Neuroscience Imaging Research, Institute of Basic Science, Suwon, Korea, Republic of, 2Biomedical Engineering, Sungkyungkwan University, Suwon, Korea, Republic of, 3Korea Brain Research Institute, Daegu, Korea, Republic of, 4Physiology, Sungkyunkwan University, Suwon, Korea, Republic of, 5Radiology, Samsung Medical Center, Seoul, Korea, Republic of

1Center for Neuroscience Imaging Research, Institute of Basic Science, Suwon, Korea, Republic of, 2Biomedical Engineering, Sungkyungkwan University, Suwon, Korea, Republic of, 3Korea Brain Research Institute, Daegu, Korea, Republic of, 4Physiology, Sungkyunkwan University, Suwon, Korea, Republic of, 5Radiology, Samsung Medical Center, Seoul, Korea, Republic of

Synopsis

Keywords: Alzheimer's Disease, fMRI (task based)

Alzheimer Disease is a neurodegenerative disease that exhibits memory and cognitive deficits. Majority of research has targeted these late-stage biomarkers as treatment targets, yet all have failed in the clinical settings. Detection of early biomarkers is becoming imperative that can be easily and effectively used. fMRI is a quick and non-invasive procedure that can map whole brain activity. Here we use sensory evoked fMRI in a AD mouse model to show longitudinal changes in brain response that can be potential biomarkers for early AD.Introduction

Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) is a degenerative neurological disease that is characterized with deficits in memory and cognitive function and late-stage appearance of parenchymal amyloid plaques and neuronal neurofibrillary tangles. A vast majority of work has targeted these late-stage biomarkers with little success when translated to clinical settings. Research has thus shifted towards detecting early biomarkers before clinical symptoms appear as a method to study and treat AD. To date, the most accurate early biomarkers are through amyloid positron emission tomography (PET) and fludeoxyglucose PET (FDGPET) with recent advances in detecting cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) amyloid beta. However, these methods are difficult to utilize as tools to screen the general population due to the use of radiotracers for PET and the invasive nature of CSF collection. Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) is a quick and noninvasive way to detect whole-brain activity through the indirect hemodynamic response of the brain. Task studies has shown hyperactive hippocampus in presymptomatic people; however, the difficult nature of the task limits its applicability. Here, we use sensory stimulation mouse fMRI to show characterizable biomarkers in a mouse model of AD which contains the human Swedish, Dutch, and Iowa mutations (TgSwDI).Methods

Twenty-three (WT n = 12; TgSwDI n = 11) mice were scanned longitudinally at the age of 2, 3, and 6 months via sensory stimulation fMRI. Mice were scanned at 15.2 T Bruker Biospec System under continuous i.v. ketamine/xylazine anesthesia. Sensory stimulation consisted of either binocular visual, electrical right whisker-pad, or olfactory stimulation in a randomized block design. Images were preprocessed and analyzed via GLM and BOLD response was quantified by calculating the area-under-curve values of the BOLD signal. A separate group of 30 mice (WT n = 15, TgSwDI n = 15) was used for the active place avoidance task (APAT) which tests spatial memory. A separate cohort was used at each age group instead of performing the task longitudinally due to the short gap between 2- and 3-month age group.Results

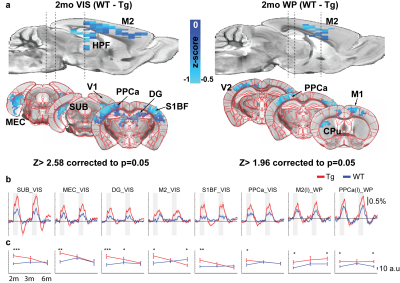

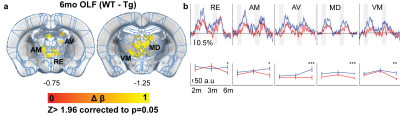

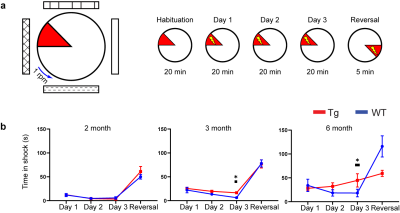

At 2 months of age, TgSwDI presented with hyperactive BOLD response in the hippocampal formation (dentate gyrus (DG), subiculum (SUB), and medial entorhinal cortex (MEC)), posterior parietal cortex (PPCa), secondary motor cortex (M2), and primary somatosensory barrel cortex (S1BF) from visual stimulation when compared to wild-type littermates (Figure 1a, b). Similarly, whisker-pad stimulation resulted in hyperactive response in PPCa, secondary visual cortex (V2), M2, and the ipsilateral motor cortex (M1). Olfactory stimulation did not result in differences between Tg and WT. AUC of the BOLD signal was calculated and plotted at each age point to show the progression of hyperactivity of each region (Figure 1c). Tg hyperactivity was mostly detected only at 2 month of age, and response became similar to WT mice by 3 month of age in most regions from VIS stimulation. Interestingly, WP stimulation resulted in hyperactive response in Tg mice through all age points. At 6 months of age, olfactory stimulation (OLF) resulted in hypoactive response in the thalamus in TgSwDI mice (Figure 2). Regions include nucleus reuniens (RE), anteromedial (AM), anteroventral (AV), mediodorsal (MD), and ventromedial (VM) thalamus. AUC of the BOLD response was only significantly different at 6 months of age (Figure 2b). APAT results show spatial memory deficits at 3 and 6 months with no difference at 2 months between Tg and WT (Figure 3).Discussion

The TgSwDI model is an AD model in which amyloid plaques are detected in vascular walls in the subiculum at 3 months of age. Spatial memory deficits were also detected at 3 months which coincide with our results. We thus chose 2 months as an early presymptomatic AD stage and detected hyperactive areas that seem to return to normal by 6 months. Interestingly, it appears these vascular plaques, which appear in the thalamus and cortex at 6 months, do not affect the BOLD response as VIS stimulation did not differ between Tg and WT at 3 or 6 months (Figure 1c). WP stimulation on the other hand resulted in hyperactive response in M2 and PPCa throughout all ages. On the contrary, OLF stimulation at 6 months resulted in hypoactive response in the thalamus in the TgSwDI model (Figure 2). Of particular note is the different response in M2 from VIS and WP stimulation (Figure 1c). The different response trajectory at each age suggests stimulation modality dependent response. Surprisingly, none of the primary sensory cortex (primary visual, somatosensory, or piriform cortex) showed any differences between Tg and WT at all ages. This suggests the primary sensation may be left intact in the TgSwDI model, but the human mutations result in polymodal or extrasensory network modifications which can be further investigated with mouse fMRI.Conclusion

We show the validity and utility of mouse fMRI for further AD research by showing hyperactivity in the hippocampal formation and polymodal areas without hyperactivity in the primary sensory cortices from sensory stimulation as early AD biomarkers. Furthermore, we show that hyperactivity does not coincide with spatial memory deficits. These may pave way for further mechanistic studies for AD research with mouse fMRI.Acknowledgements

No acknowledgement found.References

No reference found.Figures

Figure 1. BOLD response at 2 months shows hyperactivity in Tg.

a) Two-sample t-test from visual (VIS) and whisker-pad (WP) stimulation

b) BOLD time course from each region

c) AUC values from each region plotted throughout each age

Figure 2. BOLD response at 6 months show thalamic hypoactiviy in Tg from olfactory stimulation

a) Two-sample t-test from olfactory (OLF) stimulation

b) BOLD time course from each region and corresponding AUC values throughout time.

Figure 3. APAT shows spatial memory deficits at 3 and 6 months in Tg.

a) Task diagram and experimental timeline

b) Time in shock zone plotted throughout each experiment day

DOI: https://doi.org/10.58530/2023/3318