3288

HyperCEST Potential of Members of the Cucurbit[n]uril Family: Revised Signal Assignment and Suitable Host Identification with Accelerated MRI1Translational Molecular Imaging, Deutsches Krebsforschungszentrum (DKFZ), Heidelberg, Germany, 2Biomedical Magnetic Resonance, Physikalisch-Technische Bundesanstalt (PTB), Berlin, Germany

Synopsis

Keywords: Contrast Agent, CEST & MT

The full potential of the ultra-sensitive approach of HyperCEST MRI crucially depends on host structures with efficient release of hyperpolarized 129Xe. Cucurbit[n]urils (CB6 and CB7) have been proposed as promising candidates but a quantitative analysis of CEST signatures yet remained an open question. Here, we use MRI-derived z-spectra of multiple samples which provide strong evidence that CB7 is unsuitable as CEST agent and that previously observed signals are solely assigned to CB6 which is also side product in CB7 synthesis. Image acquisition with >20-fold acceleration for the 4-dimensional datasets is possible without compromising a detailed quantitative analysis.

Introduction

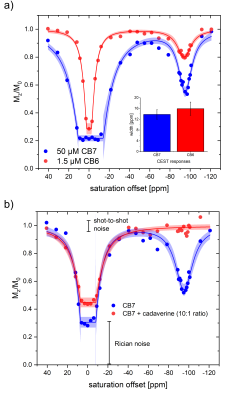

HyperCEST MRI combines the benefits of two amplification approaches, namely hyperpolarization and chemical exchange saturation transfer of 129Xe and achieves nanomolar detection limits. Its full potential crucially depends on host structures with efficient Xe exchange rates. Cucurbit[n]urils have been proposed as HyperCEST agents1–3 where the macrocyclic hosts with n = 6 or 7 (CB6/CB7) are being discussed as the most potent ones. Commercially available CB6 has been used in preclinical MRI studies4,5 but required mM concentrations due to blocking by competitive guests while suffering from poor water solubility. This requires the presence of Na+ ions that in turn decelerates the desired efficient exchange rate significantly.6 CB7, however, comes with much better solubility and has been used to design switchable HyperCEST agents in the form of rotaxanes.7,8 Its larger cavity compared to CB6 should provide accelerated exchange and cause substantial line broadening of the CEST response that could not yet be observed in experimental data (Fig. 1a). This prompted us to compare the HyperCEST signatures of both hosts in a study with detailed CEST analysis and selective competitive displacement guests (Fig. 1b).Materials and Methods

129Xe MRI was performed on a 9.4 T micro-imaging system with a 10 mm double-resonant probe (1H/129Xe). Hyperpolarization of 129Xe was achieved with a custom-built polarizer for spin exchange optical pumping (SEOP) using a gas mixture of 5% Xe (no isotopic enrichment), 10% N2 and 85% He at a total pressure of 4.5 bar. 100 ml min-1 of the total gas flow was bubbled into the sample for 15 s for each acquisition. The concentration of detectable 129Xe in solution under these conditions is ca. 260 µM, which is ~4 × 105-times less than the spin concentration for 1H MRI of pure water. We thus chose a keyhole-based acquisition technique (CAVKA9) that improves the acquisition of image-derived z-spectra without excessive increase of the acquisition time. MRI scans were collected from a ‘‘double phantom’’ consisting of two concentric NMR tubes (5 mm and 10 mm diameter), which form two separated compartments of 600 µl and 900 µl, respectively. Samples from commercially available CB7 and CB6 were tested against each other and in the presence of the competitive guests cis-1,4-bis(aminomethyl)cyclohexane (1), cadaverine (2), and putrescine (3). Spectra were analyzed with exponential Lorentzian line shapes according to the Full HyperCEST model (FHC).Results

Unexpectedly, HyperCEST spectra from commercially available CB6 and CB7 exhibit identical chemical shifts of the saturation responses at -95 ppm in pure water. Moreover, the FWHM of the CEST responses is practically identical, thus pointing towards the same exchange kinetics (see Fig. 2a). This indicates that CB7 has presumably no resolved CEST signal but only provides labile interactions and any resolved saturation response from CB7 samples actually originates from residual CB6. Initial quantitative FHC analysis based on the depolarization rate λ points to an impurity of ca. 3.9 µM CB6 in a nominal 50 µM CB7 solution. Guest 1 that can displace Xe from the CB7 cavity but that is too large to fit into the CB6 cavity showed no impact on the HyperCEST signal at -95 ppm of a solution of commercially available CB7 at equimolar concentrations. However, the addition of 2 or 3, both being guests that have higher affinity for CB6 than for CB7, showed complete loss of the CEST response at substoichiometric concentrations. An example is given in Fig. 2b with the addition of guest 2 at a ratio of 1:10 relative to the nominal CB7 concentration. Overall, the quantitative HyperCESTanalysis shows a consistent CB6 impurity of ca. 8% in CB7. The view sharing approach and side-by-side acquisition of two samples used for the acquisition of the Xe MRI series showed great improvement with significantly reduced (~22-fold) acquisition time compared to conventional HyperCEST analysis. The image noise due to low spin density is a minor issue as the quality of the quantitative analysis is dominated by the shot-to-shot noise that is low for a SEOP polarizer which operates in continuous flow mode (see Fig. 2b).Discussion and Conclusion

Bare CB7 with unrestricted access to its cavity only provides fast Xe exchange with no resolved HyperCEST response. Thus, the previous assumption that CB7 could become a powerful HyperCEST agent must be substantially revised. CB6 is present as substantial impurity in CB7 raw material (ca. 8%) at least from some commercial supplies. CB6 provides a clear CEST response where Xe can be easily displaced by competitive guests. These conditions can be easily controlled in vitro but since these competitors could also occur in vivo, the dilemma of the need for high CB6 concentrations to provide a measurable pool of bound Xe in vivo (with reduced exchange kinetics) remains and motivates the search for alternative molecular designs. An accelerated screening of such designs is possible with view sharing techniques that update only the most relevant parts of k-space when encoding the imaging series along the spectral dimension. Such techniques enable to concentrate the image noise as a Rician noise floor in the spectra that does not hamper detailed FHC analysis.Acknowledgements

We thank Prof. Dr. Andreas Hennig for the useful and informative discussions regarding the different host–guest dynamics and affinities. We acknowledge financial support by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (Koselleck Grant No. 316693477/SCHR 995/5-1) and by the Dieter Morszeck Stiftung.References

1. Kunth, M., Witte, C., Hennig, A. & Schröder, L. Identification, classification, and signal amplification capabilities of high-turnover gas binding hosts in ultra-sensitive NMR. Chem. Sci. 6, 6069–6075 (2015).

2. Wang, Y. & Dmochowski, I. J. Cucurbit[6]uril is an ultrasensitive 129Xe NMR contrast agent. Chem. Commun. 51, 8982–8985 (2015).

3. Schnurr, M., Sloniec-Myszk, J., Döpfert, J., Schröder, L. & Hennig, A. Supramolecular Assays for Mapping Enzyme Activity by Displacement-Triggered Change in Hyperpolarized 129Xe Magnetization Transfer NMR Spectroscopy. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 54, 13444–13447 (2015).

4. Hane, F. T. et al. In vivo detection of cucurbit[6]uril, a hyperpolarized xenon contrast agent for a xenon magnetic resonance imaging biosensor. Sci. Rep. 7, 41027 (2017).

5. McHugh, C. T., Kelley, M., Bryden, N. J. & Branca, R. T. In vivo hyperCEST imaging: Experimental considerations for a reliable contrast. Magn. Reson. Med. 87, 1480–1489 (2022).

6. Kim, B. S. et al. Water soluble cucurbit[6]uril derivative as a potential Xe carrier for 129Xe NMR-based biosensors. Chem. Commun. 2756–2758 (2008) doi:10.1039/B805724A.

7. Truxal, A. E., Cao, L., Isaacs, L., Wemmer, D. E. & Pines, A. Directly Functionalized Cucurbit[7]uril as a Biosensor for the Selective Detection of Protein Interactions by 129Xe hyperCEST NMR. Chem. – Eur. J. 25, 6108–6112 (2019).

8. Finbloom, J. A. et al. Rotaxane-mediated suppression and activation of cucurbit[6]uril for molecular detection by 129Xe hyperCEST NMR. Chem. Commun. (2016) doi:10.1039/C5CC10410F.

9. Morik, H.-A., Schuenke, P. & Schröder, L. Rapid analytical CEST spectroscopy of competitive host–guest interactions using spatial parallelization with a combined approach of variable flip angle, keyhole and averaging (CAVKA). Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 24, 12126–12135 (2022).

Figures