3277

Saturation Transfer MR Fingerprinting (ST-MRF): free bulk water, semisolid macromolecule, and amide proton parameter quantification1Russell H. Morgan Department of Radiology and Radiological Science, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: CEST & MT, CEST & MT

Conventional saturation transfer MRI approaches, such as magnetization transfer contrast (MTC) and chemical exchange saturation transfer (CEST) MRI, acquire qualitative contrast weighted images, without specific information on the quantitative parameters affecting contrast, namely proton exchange rate and concentration. In addition, the contrast weighted images are highly dependent on scan parameters and data acquisition strategies. Here, we developed a fast, quantitative saturation transfer (ST) imaging technique based on MR fingerprinting principles to simultaneously estimate free bulk water, semisolid macromolecule, and amide proton-related parameters. The approach was evaluated with Bloch simulation and synthetic MRI analysis using in vivo human brains.Introduction

Saturation transfer (ST) MRI provides unique and flexible contrast mechanisms, including semisolid magnetization transfer contrast (MTC) and chemical exchange saturation transfer (CEST)1,2. Conventionally, the saturation transfer effects are measured with contrast weighted images, which have a dependence on multiple parameters, including proton concentration, average exchange rate, and free water relaxation properties3,4. To make matters worse, the qualitative measurement is influenced by imaging scan parameters, particularly RF saturation conditions5-7. Recently, quantitative saturation transfer imaging techniques has been developed by integrating an RF saturation scheme with MR fingerprinting (MRF)8-14. Although recent advances in deep-learning improved reconstruction accuracy and time, the reliable estimation of tissue parameters in a complex multiple-exchange model needs a deeper and more complex network that can extract information of the low concentration of solute protons from MRF. Herein, we proposed a Bloch-equation-informed deep learning framework that simultaneously estimated free bulk water, semisolid MTC, amide proton-related parameters, and B0 inhomogeneity in a single scan. In vivo tissue parameters were evaluated by synthetic MRI analysis because a “true” gold standard does not currently exist for absolute APT quantification of in vivo brain tissue.Methods

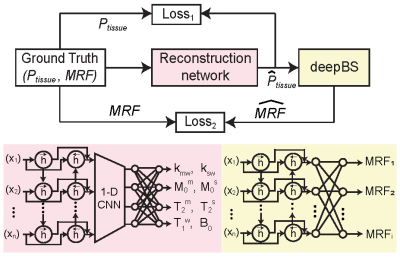

Nine healthy volunteers (four females and five males, age: 36.4 ± 3.8 years) were recruited for the study after informed consent was obtained in accordance with the IRB requirement. 3D MRF images were acquired with a multi-shot turbo spin-echo sequence with an RF saturation-encoded MRF schedule. Each frequency offset (Ω) was applied along with varied saturation strengths (B1), saturation times (Ts), and relaxation delay times (Td) to produce significant spatial and temporal incoherence. A deep-learning architecture consisted of reconstruction and Bloch simulator (deepBS) networks to estimate tissue parameters and synthesize MR fingerprints, respectively (Fig. 1). The deepBS was pre-trained and integrated in the architecture because the three-pool exchange model with a super-Lorentzian symmetric MTC lineshape requires high computational cost. The reconstruction networks estimated semisolid macromolecular proton exchange rates (kmw), concentration (M0m), T2 relaxation times (T2m), free water T1 relaxation times (T1w), B0 map, amide proton exchange rates (ksw), concentration (M0s) and T2 relaxation times (T2s) parameters. The framework was trained on 30 million simulated datasets. The Bloch simulation was performed with randomly generated tissue parameters from their maximum to minimum range: kmw [5, 100] Hz, M0m [2, 17] %, T2m [1, 100] µs, T1w [0.2, 3] s, B0 [-0.5, 0.5] ppm, ksw [5, 500] Hz, M0s [1, 500] mM and, T2s [0.01, 1] s. The performance of the deepBS and MRF reconstruction was evaluated using numerical phantoms. For evaluation of in vivo results, synthesized saturation transfer contrast-weighted images were compared with the experimental measurement acquired from new imaging scan parameters.Results and Discussion

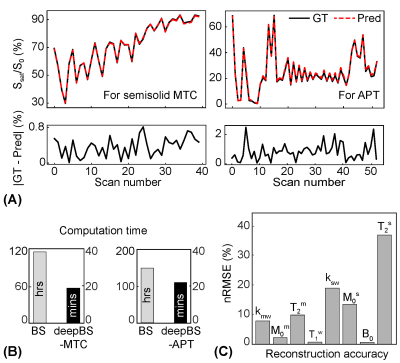

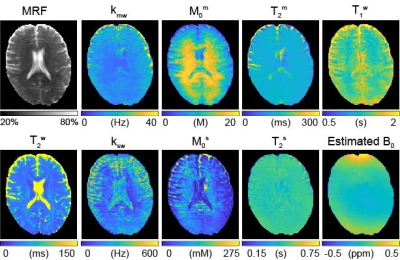

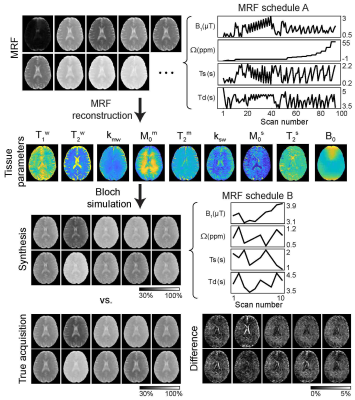

For the simulations, MRF estimated from the deepBS were in excellent agreement with the ground-truths as shown in Fig. 2. Notably, the deepBS achieved significantly higher computation efficiency (~388x) than the conventional Bloch simulation. The normalized root mean square error (nRMSE) were 8.33% for kmw, 3.08% for M0m, 1.03% for T2m, 0.72% for T1w, 20.33% for ksw, 13.21% for M0s, 35.73% for T2s, and 0.57% for B0 at SNR of 194. The reconstruction accuracy was evaluated on numerical phantoms as shown in Fig.3. Overall, the nRMSE values of the estimation of the amide proton parameters were lower than those of the estimation of the free water and semisolid MTC parameters due to the lower MR signal from low-concentration amide protons, which is very sensitive to the noise level. Quantitative tissue parameter maps obtained from ST-MRF are shown in Fig. 4. A sufficient number of dynamic scans (93 scans) was acquired to extract APT parameter information, since the sensitivity of the amide proton exchange rate and concentration to MRF signal intensities is inherently low. Total scan time was ~10 min for nine slices with a resolution of 1.8x1.8x4 mm3 and reconstruction time was ~132 sec for 256x256x9x93. The amide proton exchange rates for gray and white matter were 206 ± 45 Hz and 115 ± 18 Hz, respectively, and concentrations of 74 ± 19 mM and 106 ± 16 mM, respectively. To evaluate the proposed method, the contrast weighted images were synthesized and compared with experimental measurements (Fig. 5). The tissue parameters were estimated by ST-MRF acquired from MRF schedule A, and then ten contrast-weighted images were synthesized by inserting the tissue estimates into the forward Bloch transform with a new MRF schedule B. The synthetic images were in excellent agreement with the experimentally measured images and the average nRMSE was only 2.3%. The estimation of the in vivo tissue parameters satisfied the new RF saturation conditions that would guarantee a solution of the ill-posed inverse Bloch equation problem.Conclusions

We developed a saturation transfer MRF framework to simultaneously estimate multiple tissue parameters in a single scan. The deep Bloch simulator significantly reduced the computation time for the generation of training datasets and the reconstruction network demonstrated remarkable quantification accuracy on the numerical phantom. This study obtained reasonable in vivo results and shows promise to advance quantitative saturation transfer imaging. The proposed ST-MRF will allow quantitative assessment of exchange rates and concentrations in disease, which may have clinical applications.Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by grants from the National Institutes of Health.References

1. van Zijl PCM, Lam WW, Xu J, Knutsson L, Stanisz GJ. Magnetization Transfer Contrast and Chemical Exchange Saturation Transfer MRI. Features and analysis of the field-dependent saturation spectrum. Neuroimage 2018;168:222-241.

2. Ward KM, Aletras AH, Balaban RS. A new class of contrast agents for MRI based on proton chemical exchange dependent saturation transfer (CEST). J Magn Reson 2000;143:79-87.

3. Zhou J, Heo HY, Knutsson L, van Zijl PCM, Jiang S. APT-weighted MRI: Techniques, current neuro applications, and challenging issues. J Magn Reson Imaging 2019;50(2):347-364.

4. Zu Z. Towards the complex dependence of MTRasym on T1w in amide proton transfer (APT) imaging. NMR Biomed 2018;31(7):e3934.

5. Heo HY, Lee DH, Zhang Y, Zhao X, Jiang S, Chen M, Zhou J. Insight into the quantitative metrics of chemical exchange saturation transfer (CEST) imaging. Magn Reson Med 2017;77(5):1853-1865.

6. Zaiss M, Xu J, Goerke S, Khan IS, Singer RJ, Gore JC, Gochberg DF, Bachert P. Inverse Z-spectrum analysis for spillover-, MT-, and T1 -corrected steady-state pulsed CEST-MRI - application to pH-weighted MRI of acute stroke. NMR Biomed 2014;27:240-252.

7. Sun PZ, van Zijl PCM, Zhou J. Optimization of the irradiation power in chemical exchange dependent saturation transfer (CEST) experiments. J Magn Reson 2005;175:193-200.

8. Kim B, Schar M, Park H, Heo HY. A deep learning approach for magnetization transfer contrast MR fingerprinting and chemical exchange saturation transfer imaging. Neuroimage 2020;221:117165.

9. Cohen O, Huang S, McMahon MT, Rosen MS, Farrar CT. Rapid and quantitative chemical exchange saturation transfer (CEST) imaging with magnetic resonance fingerprinting (MRF). Magn Reson Med 2018;80(6):2449-2463.

10. Heo HY, Han Z, Jiang S, Schar M, van Zijl PCM, Zhou J. Quantifying amide proton exchange rate and concentration in chemical exchange saturation transfer imaging of the human brain. Neuroimage 2019;189(1):202-213.

11. Perlman O, Farrar CT, Heo HY. MR fingerprinting for semisolid magnetization transfer and chemical exchange saturation transfer quantification. NMR Biomed 2022:e4710.

12. Perlman O, Zhu B, Zaiss M, Rosen MS, Farrar CT. An end-to-end AI-based framework for automated discovery of rapid CEST/MT MRI acquisition protocols and molecular parameter quantification (AutoCEST). Magn Reson Med 2022;87(6):2792-2810.

13. Kang B, Kim B, Park H, Heo HY. Learning-based optimization of acquisition schedule for magnetization transfer contrast MR fingerprinting. NMR Biomed 2022;35(5):e4662.

14. Kang B, Kim B, Schar M, Park H, Heo HY. Unsupervised learning for magnetization transfer contrast MR fingerprinting: Application to CEST and nuclear Overhauser enhancement imaging. Magn Reson Med 2021;85(4):2040-2054.

Figures