3234

IMPROVED EX-VIVO IMAGING USING BRAIN & CONTAINER-SPECIFIC 3D-PRINTED HOLDERS1Department of Biomedical Engineering, McGill University, Montreal, QC, Canada, 2McConnell Brain Imaging Center, Montreal Neurological Institute and Hospital, Montreal, QC, Canada

Synopsis

Keywords: Data Acquisition, Ex-Vivo Applications, Brain Ex-Vivo MRI

Depending on the medium, it might be difficult to maintain the brain stable during ex-vivo imaging. In addition, the SNR might not be homogeneous. We propose using brain and container-specific 3D-printed models for holding the brain. The method requires preliminary imaging of the container and the brain. Then, a 3D-printed model is created, with profiles that match the surface of the brain on one side and the inner surface of the container on the other. The holder is designed to maintain the brain stable in space, where the SNR is high and homogeneous, while allowing contact with the immersion fluid.INTRODUCTION

Ex-vivo imaging plays an important role in neuroimaging research. Ex-vivo images obtained at very high-resolution support the validation of quantitative MRI and diffusion neuroimaging methods. However, setting up ex-vivo imaging to achieve high-resolution images free of artifacts is challenging. The challenges include finding a proper RF coil with receiving elements that are sufficiently close to the brain tissue to provide high SNR as well as uniform sensitivity. In addition, the placement and method of holding the brain stable inside the container have a direct effect on the quality of the image obtained. To mitigate the latter challenges, we propose the use of container-specific and brain-specific 3D-printed holders designed using preliminary data obtained during the study development/planning scans.METHODS

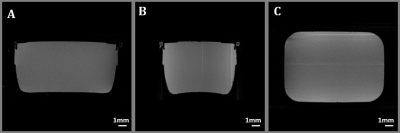

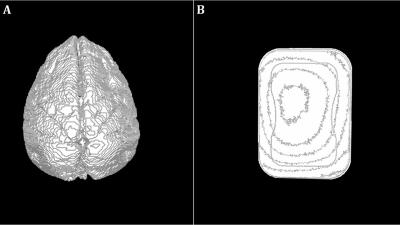

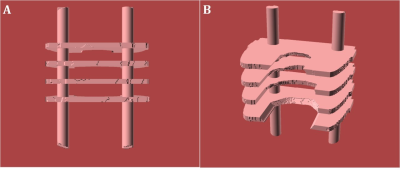

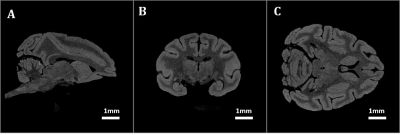

We performed ex-vivo imaging of a fixed brain of a macaque primate using a Siemens 3T Magnetom Prisma scanner. We used the 16-channel knee/ankle coil for imaging, as it has a flat base and provides high and homogeneous SNR. We used a rectangular container that is sufficiently large to hold a macaque brain. The preliminary session included imaging the container filled with salted water. We also obtained T1w MPRAGE and 10 PD-weighted GRE images. In order to obtain the container profile, we acquired MPRAGE images with isotropic voxels of 0.5 mm, a matrix of 160 X 320, TR = 2,650 ms, TE = 3.02 ms, TI = 1100 ms, FA = 9 degrees, and acquisition time (TA) 7:32 minutes. In order to obtain the sensitivity map, we acquired multiple PD-weighted (PDw) ME-GRE images with isotropic 0.33 mm voxels, a matrix of 235 x 480, TR = 14 ms, TE = 5.40 ms, and TA = 03:57 minutes. Separately, we imaged the primate brain with isotropic voxels of 0.5 mm. Using the PDw GRE images of the container, we computed an SNR map (by computing the mean over 10 scans and dividing it by the SD) to identify the area of the optimal uniform signal. We then created a 3D model based on the internal profiles of the container obtained from the averaged T1w image of the container. We also extracted the surface of the brain from separate brain images1-4. Using the two surfaces, we create a 3D-printed holder with profiles that fit the surface of the brain on one side and the inner surface of the container on the other. The holder comprises 4 mm-thick profiles joined using rods. The holder is capable of holding the brain in the desired orientation and position. It prevents the movement of the brain due to system vibrations. The optimal position of the brain in the container is identified using the SNR map. The 3D-printed model is designed to hold the specimen in a region of approximately uniform and high SNR. We propose 2 designs. One design is for use with Fomblin or Flourinert with which the brain is pushed up against the model as the brain floats in these immersion fluids. The profiles in this design match the dorsal surface of the brain. For any Anterior-Posterior coordinate, once the profile reaches the lateral-most part of the brain, the profile is continued vertically toward the bottom of the container. In a second design, the holder’s profiles support the brain all around, for use with immersion fluids such as paraformaldehyde (PFA) and Phosphate-Buffered- Saline PBS in which the sample sinks, but its position remains unstable. The designed model is shown in Figure 3. Using the 3D-printed model, we acquired high-resolution MPRAGE images with Fluorinert as immersion media (Figure 4).RESULTS

The images of the container are presented in Figures 1. Figure 2 presents the corresponding surfaces of the inner volume of the container and the brain. The design of the 3D printed model is shown in Figure 3. To demonstrate the use of the 3D-printed model, we acquired high-resolution MPRAGE with Fluorinert as immersion media (Figure 4).CONCLUSION

We have outlined a method for obtaining consistent high-resolution ex-vivo images of high SNR and uniform signal.Acknowledgements

Funded by CIHR.References

1.M. Absinta et al., "Postmortem magnetic resonance imaging to guide the pathologic cut: individualized 3-dimensionally printed cutting boxes for fixed brains", J. N. E. N., vol. 73, no. 8, pp. 780-788, Aug. 2014.

2.D. M. Jacobowitz, "3-D Printing of a Non-Human Primate Brain Slicer for Accurate High-Resolution Sampling of Specific Regions of Fresh or Frozen Brain", J Primatology, vol. 04, no. 01, 2015.

3.N. J. Luciano et al., "Utilizing 3D Printing Technology to Merge MRI with Histology: A Protocol for Brain Sectioning", J. Vis. Exp., no. 118, 2016.

4.S. K. Boopathy Jegathambal, K. Mok, D. A. Rudko and A. Shmuel, "MRI

Based Brain-Specific 3D-Printed Model Aligned to Stereotactic Space for

Registering Histology to MRI," 2018 40th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (EMBC), 2018, pp. 802-805, doi: 10.1109/EMBC.2018.8512346.

Figures