3210

Major structural abnormalities in the alpha-synuclein mouse model of Parkinson’s Disease revealed with MR Microscopy at 16.4 T

Ruxanda Lungu Baião1, Tiago Fleming Outeiro2, and Noam Shemesh1

1Preclinical MRI, Champalimaud Research, Champalimaud Foundation, Lisbon, Portugal, 2Department of Experimental Neurodegeneration, University of Göttingen, Goetingen, Germany

1Preclinical MRI, Champalimaud Research, Champalimaud Foundation, Lisbon, Portugal, 2Department of Experimental Neurodegeneration, University of Göttingen, Goetingen, Germany

Synopsis

Keywords: Parkinson's Disease, Neurodegeneration

Parkinson's disease (PD) is associated with irreparable damage to dopaminergic neurons due to α-synuclein (aSYN) inclusions. Dopaminergic pathways include the nigrostriatal, mesolimbic, mesocortical and tuberoinfundibular systems that play vital roles. Thus, dysregulations of dopamine function may lead to brain-wide consequences. Apart from a mouse PD model of injected aSYN1, brain morphology alterations in genetic mouse models have not been described in detail using MRI. Here we explore brain morphological differences between PD models and healthy controls, crucial for further understanding of the disease. We find major morphological abnormalities in areas such as Lateral Ventricles, Corpus Callosum and the surrounding Cortex.Introduction

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is the second most widespread neurodegenerative disease worldwide1,2, typically characterized by α-synuclein (αSYN) aggregates and progressive motor deficits. In PD patients, atrophy of the brain has been observed in many cortical and subcortical areas3. Interestingly, the volume of the frontal lobe, temporoparietal junction, parietal lobe, insula, anterior cingulate cortex, basal ganglia, and thalamus were found to be increased in PD patients4, suggesting that the dopaminergic dysfunction extends well beyond the dopaminergic pathway itself.Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can provide the means for investigating these changes. In the context of PD animal models, MRI has been used to characterize brain-wide microstructural changes in several animal models, but with relatively low resolution4,5. Compared with other transgenic6,7 or toxin-based models8 the αSYN transgenic model benefits from extensive characterization and reproduces several features of the sporadic disease9.

We therefore sought to use a powerful MR Microscopy approach at ultrahigh field to investigate brain-wide morphological differences in a mouse model of PD. We use here the transgenic model expressing human αSYN, leading to a PD-like phenotype. This model has been broadly characterized in terms of protein dysfunction and how they affect different areas of the brain at a molecular level by histology5,10 and transcriptomics11, as well as the behavior deficits12.

Methods

All animal experiments were pre-approved by the competent institutional and national authorities and were carried out according to European Directive 2010/63.Specimen preparation: The mouse line used in this study is the αSYN transgenic model (C57BL/6-DBA/2 Thy1-αSYN). Transgenic mice (N=3) and their wildtype littermates (healthy controls, N=2), were perfused at 9 months of age. Animals were deeply anesthetized by intraperitoneal injection of acepromazine (10:1 in volume, dose 2.5mL/g) and transcardially perfused with 100mL phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) first, followed by 70mL 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA)/PBS mixed with Gadolinium (Dotarem 279.32mg/ml) at a concentration of 10mM per volume (a total of 400ml). The rate of infusion was 10mL/min for all solutions. The extracted brains were stored in the same solution as used for perfusion at 48C. Between the multiple MRI scans of the same sample, the tissue specimens were stored in the PFA/PBS solution with the same Gadolinium concentration as used for perfusion fixation. Previous to scanning, specimens were placed in a 10mm NMR tube with Fluorinert.

MRI acquisitions: MRI scans were performed at 37C using a 16.4T Aeon Bruker scanner equipped with a Micro5 probe capable of producing up to 3000mT/m.

MGE parameters: Echo Time: 1.75ms, 4.25ms, 6.75ms, 9.25ms; Repetition Time: 100ms; Averages: 2; Matrix size: 430x250x250; Field of View: 17mm x 10mm x 10mm; Spatial resolution: 40μm x 40μm x 40μm; Flip Angle: 90.

RARE parameters: Echo Time: 6 and 12ms; Repetition Time: 120ms; Averages: 4; Matrix size: 430x250x250; Field of View: 17mm x 10mm x 10mm; Spatial resolution: 40μm x 40μm x 40μm; Rare factor: 2.

Results

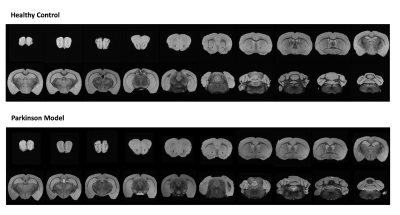

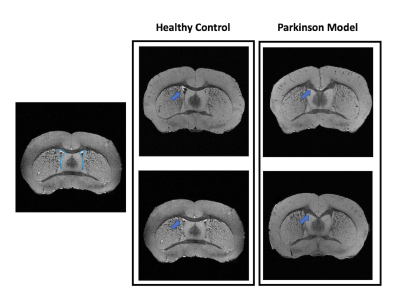

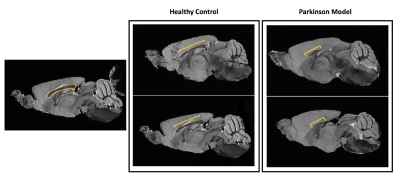

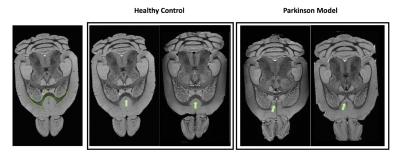

Figure 1 shows MGE’s first echo in 20 slices (out of the 250 slices acquired) covering the entire length of the brain for a representative animal from each group. Signal to noise was above 30 for all specimens.Already upon these preliminary scans, dramatic differences were observed between the groups. For instance, the Lateral Ventricles appeared to be drastically reduced in the PD model (Fig.2). Choroid plexus is nearly completely absent in the PD model. The Corpus Callosum is degenerate and at least half of it is missing (Fig.3) when compared to the healthy controls; furthermore, a thinning of the corpus callosum is also evident in the more lateral aspects. The absence of ventricles and corpus callosum are accompanied by a collapse of the cortex (Fig.4). This is clearly observed in regions such as the Prelimbic cortex and frontal cortex that seem to merge into the Lateral septal nucleus. Interestingly, the cortex in the PD appears thicker than in the controls.

Discussion

Our findings suggest that the αSyn mouse model involves dramatic brain-wide damage that extends well beyond the dopaminergic system. This study only examined these effects qualitatively, but the results were consistent across 3 PD brains and further quantitative analysis will ensue. One interesting finding here is the near complete absence of a choroid plexus in the PD brain, which may indicate on stress to the clearance of αSyn aggregates in the brain; future experiments with perfusion MRI may assist in understanding the functional relevance of this finding.Conclusion

We find gross neuroanatomical deficits in major brain structures in the αSyn mouse model of PD.Acknowledgements

CONGENTO, PORTUGAL 2020 European Regional Development Fund (ERDF) and Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia LISBOA-01-0145-FEDER-022170.References

- Chu WT, DeSimone JC, Riffe CJ, et al. α-Synuclein Induces Progressive Changes in Brain Microstructure and Sensory-Evoked Brain Function That Precedes Locomotor Decline. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2020;40(34):6649-6659. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0189-20.20202.

- Calabresi P, di Filippo M. The changing tree in Parkinson’s disease. Nat Neurosci. Published online 2015. doi:10.1038/nn.40923.

- Prakash K, Bannur B, Chavan M, Saniya K, Sailesh K, Rajagopalan A. Neuroanatomical changes in Parkinson′s disease in relation to cognition: An update. J Adv Pharm Technol Res. 2016;7(4):123. doi:10.4103/2231-4040.1914164.

- Cerasa A, Messina D, Pugliese P, et al. Increased prefrontal volume in PD with levodopa-induced dyskinesias: A voxel-based morphometry study. Movement Disorders. 2011;26(5):807-812. doi:10.1002/mds.236605.

- Lam HA, Wu N, Cely I, et al. Elevated tonic extracellular dopamine concentration and altered dopamine modulation of synaptic activity precede dopamine loss in the striatum of mice overexpressing human α-synuclein. J Neurosci Res. 2011;89(7):1091-1102. doi:10.1002/jnr.226116. Cong L, Muir ER, Chen C, et al. Multimodal MRI evaluation of the mitopark mouse model of Parkinson’s disease. PLoS One. Published online 2016. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.015188410.

- Yao L, Wu J, Koc S, Lu G. Genetic Imaging of Neuroinflammation in Parkinson’s Disease: Recent Advancements. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2021;9. doi:10.3389/fcell.2021.65581911.

- Fleming SM, Salcedo J, Hutson CB, et al. Behavioral effects of dopaminergic agonists in transgenic mice overexpressing human wildtype α-synuclein. Neuroscience. 2006;142(4):1245-1253. doi:10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.07.0059.

- Hisahara S, Shimohama S. Toxin-Induced and Genetic Animal Models of Parkinson’s Disease. Parkinsons Dis. 2011;2011. doi:10.4061/2011/95170912.

- Fernagut PO, Chesselet MF. Alpha-synuclein and transgenic mouse models. Neurobiol Dis. Published online 2004. doi:10.1016/j.nbd.2004.07.00113.

- Overk CR, Cartier A, Shaked G, et al. Hippocampal neuronal cells that accumulate α-synuclein fragments are more vulnerable to Aβ oligomer toxicity via mGluR5 – implications for dementia with Lewy bodies. Mol Neurodegener. 2014;9(1):18. doi:10.1186/1750-1326-9-187.

- Cabeza-Arvelaiz Y, Fleming SM, Richter F, Masliah E, Chesselet MF, Schiestl RH. Analysis of striatal transcriptome in mice overexpressing human wild-type alpha-synuclein supports synaptic dysfunction and suggests mechanisms of neuroprotection for striatal neurons. Mol Neurodegener. 2011;6(1):83. doi:10.1186/1750-1326-6-838.

- Fernagut PO, Chesselet MF. Alpha-synuclein and transgenic mouse models. Neurobiol Dis. Published online 2004. doi:10.1016/j.nbd.2004.07.001

Figures

Figure 1: Anatomical coronal sequential representation of a whole brain structure obtained through MGE MRI sequence at the 16.4T scanner with an isotropic resolution of 40µm. Representative 20 slices out of 250 for each animal were chosen. The upper panel represents a healthy control. The lower panel represents a Parkinson’s Disease mouse model.

Figure 2: Anatomical coronal representation of 2 healthy control animals (left panel) versus 2 PD mice (right panel). The blue arrow points out the presence/absence of the Lateral Ventricle. We can observe that in the Parkinson model the ventricle is completely absent.

Figure 3: Anatomical sagittal representation of 2 healthy control animals (left panel) versus 2 PD mice (right panel). The yellow bracket highlights the length of the visible corpus callosum from this perspective. It is clear how much reduced is this structure in the PD animals. It is also interesting to point out the higher volume of the cortex in the PD mice relatively to their healthy littermates.

Figure 4: Anatomical axial representation of 2 healthy control animals (left panel) versus 2 PD mice (right panel). The green circle highlights the region where the cortex structure is different in the PD mice when compared with the healthy controls. In the PD mice, the intrusion of the cortex into the underneath structures is clear, as well as the thin thickness of the corpus callosum right beside.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.58530/2023/3210