3201

Axonal abnormalities in deep brain nuclear pathways across multiple neurotransmitter systems in de novo Parkinson’s disease patients1Graduate Institute of Medicine, Yuan Ze University, Taoyuan City, Taiwan, 2Department of Diagnostic Radiology, Singapore General Hospital, Singapore, Singapore, 3Duke-NUS Medical School, Singapore, Singapore, 4Department of Traumatology, Far Eastern Memorial Hospital, New Taipei City, Taiwan, 5Department of Neurology, National Neuroscience Institute – SGH Campus, Singapore, Singapore, 6Department of Neurology, Far Eastern Memorial Hospital, New Taipei City, Taiwan

Synopsis

Keywords: Parkinson's Disease, Diffusion Tensor Imaging

The present study systematically and comprehensively reviewed the axonal pathways projecting from the deep brain nuclei that are emerging targets for treating Parkinson’s disease (PD). We tracked 124 deep brain nuclear pathways across different neurotransmitters systems in the high angular HCP-1065 diffusion MRI template using diffusion MRI tractography. With the trajectories of these pathways, we successfully used Parkinson's Progression Markers Initiative (PPMI) diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) data to characterize abnormal DTI changes in noradrenergic and serotoninergic pathways in relation to the severity of non-motor symptoms in de novo PD patients, suggesting a wide neural involvement of clinical PD manifestations.Introduction

Growing evidence indicates that Lewy body pathology and abnormal neurotransmitter binding in idiopathic Parkinson’s disease start from the dorsal raphe nuclei (DR) of the serotoninergic system at the early premotor stage and spread to other brain areas involved in multiple neurotransmitter systems at the later motor stage beyond the well-recognized dopaminergic deficits.1-3 It supports the Braak’s histopathological staging1 that the progressive neural damages could start from autonomic/olfactory systems and medulla, spread to pons of locus coeruleus (LC) and DR, via pedunculopontine nucleus (PPN), substantia pars compacta (SNpc), and basal forebrain (e.g., nucleus basalis of Meynert [NBM], stage 3), then to the limbic system, and terminate in multiple cortical regions. The affected brain regions with PD progression are involved in multiple neurotransmissions, thereby leading to heterogeneous clinical manifestations. However, the cost of molecular imaging to characterize multiple neurochemical deficits is extremely high, and the diffusion MRI tractography study in delineating these deep brain nuclear pathways is still lacking. We aimed to track these pathways connecting to the basal forebrain, basal ganglia, brainstem, and cerebellum in a high angular resolution diffusion MRI template (HCP-1065) in the standard stereotaxic space, with clear gray-white matter differentiation and accurate neuroanatomical labelling.4 The 8 deep brain nuclei comprising of the SNpc, ventral tegmental area (VTA), DR, median raphe nuclei (MR), LC, PPN, NBM, and subthalamic nuclei (STN) were included in this study. Next, we applied these tracked pathways to investigate the microstructural changes in de novo PD patients to validate their clinical applicability, using the multicenter Parkinson's Progression Markers Initiative (PPMI) diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) data (https://www.ppmi-info.org/).Methods and Materials

The MRI masks of deep brain nuclei, cerebrum, and cerebellum were mainly obtained from the Automated Anatomical Labelling atlas 3 (AAL3)5, Harvard Ascending Arousal Network atlas (AAN)6, and Minimum Deformation Averaging (MDA) hypothalamic atlas.7 There were 124 deep brain nuclear projections in total tracked in the Human-Connectome-Project diffusion MRI template, using DSI-studio software (https://dsi-studio.labsolver.org/). All axons were generated by the deterministic tractography algorithm8 with the following parameters: tracking threshold of quantitative anisotropy (QA)=0.008-0.04, angular threshold=40-90 degrees, step size=0.60 voxel, smoothing=0.30 voxel, the minimum fiber length=30-50 mm, maximum length=80-150 mm. The starting regions of interest (ROIs) were 8 deep brain nuclei and the terminated ROIs were cerebral and cerebellar regions over the whole brain. The selection of tracked pathway was based on previous neuroanatomical and neurophysiological studies over decades. The PPMI DTI data was processed using Q-Space Diffeomorphic Reconstruction (QSDR) provided by DSI-studio9, which generated DTI metrics in the standard common Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) space for each subject. We then compared the DTI metrics of 8 deep brain nuclear pathways between the de novo PD patients and healthy controls (HC), and correlated them with the 5 clinical PD motor/non-motor scores. To reduce multiple statistical tests, we grouped pathways projected from the same nucleus as an axonal cluster for the following statistical analyses.Results

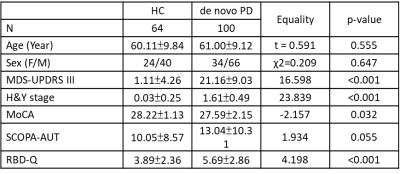

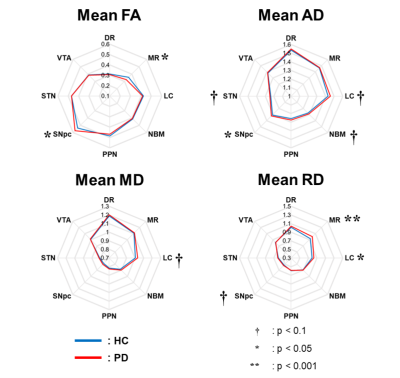

We successfully tracked 124 deep brain nuclear pathways, respectively connecting 8 deep brain nuclei to the brain-wide regions (Fig. 1), including 4 SNpc, 12 VTA, 16 LC, 20 STN, 8 DR, 6 MR, 40 NBM, 18 PPN pathways. Table 1 lists the demographic information of PPMI DTI data. 100 de novo PD patients and 64 HC subjects were included in this study. When comparing the 4 DTI metrics in 8 pathways (Fig. 2), patients showed higher SNpc (p=0.026) and lower MR fractional anisotropy (FA) (p=0.013), higher SNpc axial diffusivity (AD) (p=0.033), and higher LC (p=0.016) and MR (p=0.009) radial diffusivity (RD). Partial correlation analyses with adjustments of age and sex revealed the involvements of multiple impaired deep brain nuclear pathways in different brain dysfunctions. NBM FA was associated with autonomic dysfunctions evaluated by Scales for Outcomes in Parkinson’s disease- Autonomic (SCOPA-AUT) total scores (r=-0.155, p=0.049); DR/LC/PPN/STN/VTA FA were associated with sleep dysfunctions screened by RBD questionnaire (RBD-Q) score (r=-0.184, p=0.019; r=-0.236, p=0.003; r=-0.191, p=0015; r=-0.209, p=0.008) and DR/MR RD were associated with Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) score (r=0.173, p=0.028; r=0.163, p=0.039).Discussion

Deterministic tractography in the HCP diffusion MRI template with high angular resolution allowed us to anatomically defined 124 deep brain nuclear pathways within the white matter structures. Hence, we were able to sample DTI metrics along the spatial coordinates of these pathways defined in the MNI space via QSDR reconstruction. Interestingly, we did not only replicate the finding of higher FA in the SNpc pathway in patients but also characterized abnormal DTI metrics in MR and LC pathways. MR and LC are the main source of serotonin and norepinephrine, and the neuronal loss in these two nuclei may lead to axonal loss (FA changes) and/or demyelination (FA and RD changes) in their pathways. It implies that, when the diagnosis of PD is just confirmed in patients without medications, they have already experienced non-dopaminergic deficits, such as cognitive declines10 and sleep disorders.11 Indeed, our correlation results of PPMI DTI data also support this statement.Conclusion

Multiple deep brain nuclear pathways with abnormal DTI changes in relation to non-motor symptoms in de novo PD could be targets for pre/post-therapeutic assessments.Acknowledgements

No acknowledgement found.References

1. Braak, H., et al., Staging of brain pathology related to sporadic Parkinson's disease. Neurobiol Aging, 2003. 24(2): p. 197-211.

2. Jellinger, K.A., Pathology of Parkinson's disease. Changes other than the nigrostriatal pathway. Mol Chem Neuropathol, 1991. 14(3): p. 153-97.

3. Wilson, H., et al., Serotonergic pathology and disease burden in the premotor and motor phase of A53T α-synuclein parkinsonism: a cross-sectional study. Lancet Neurol, 2019. 18(8): p. 748-759.

4. Yeh, F.C., Population-based tract-to-region connectome of the human brain and its hierarchical topology. Nat Commun, 2022. 13(1): p. 4933.

5. Rolls, E.T., et al., Automated anatomical labelling atlas 3. Neuroimage, 2020. 206: p. 116189. 6. Edlow, B.L., et al., Neuroanatomic connectivity of the human ascending arousal system critical to consciousness and its disorders. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol, 2012. 71(6): p. 531-46.

7. Neudorfer, C., et al., A high-resolution in vivo magnetic resonance imaging atlas of the human hypothalamic region. Sci Data, 2020. 7(1): p. 305.

8. Mori, S., et al., Three-dimensional tracking of axonal projections in the brain by magnetic resonance imaging. Ann Neurol, 1999. 45(2): p. 265-9.

9. Yeh, F.C., P.F. Tang, and W.Y. Tseng, Diffusion MRI connectometry automatically reveals affected fiber pathways in individuals with chronic stroke. Neuroimage Clin, 2013. 2: p. 912-21.

10. Halliday, G.M., et al., The neurobiological basis of cognitive impairment in Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord, 2014. 29(5): p. 634-50.

11. Wilson, H., et al., Serotonergic dysregulation is linked to sleep problems in Parkinson's disease. Neuroimage Clin, 2018. 18: p. 630-637.

Figures