3193

CSF oxygenation imaging using long TE heavily T2-weighted Fluid-Attenuated Inversion Recovery1Division of MRI Research, department of Radiology, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Neurofluids, Brain

The cerebrospinal fluid plays an essential role in cerebral homeostasis, contributing to the delivery of oxygen and nutrients to brain tissue as well as clearing waste products. However, the mechanisms and functions of CSF oxygenation and their potential disturbance in pathology remain unknown. Dissolved O2 shortens T1 of water due to its paramagnetic properties. Because of its extremely long T2, selective CSF imaging can be achieved by using extremely long TE (>500ms) Spin-Echo based acquisitions. Therefore, we report here a study using ultra long TE Fluid-Attenuated Inversion Recovery to image baseline CSF oxygenation with minimal tissue contribution.Introduction

The cerebrospinal fluid plays an essential role in cerebral homeostasis, contributing to the delivery of oxygen and nutrients to brain tissue as well as clearing waste products. In the past few years, the field of neurofluids imaging has seen lots of interest and developments. The mechanisms and functions of CSF oxygenation and their potential disturbance in pathology remain unknown. Previous studies have highlighted the hyperintensity of CSF in Fluid-Attenuated-Inversion-Recovery (FLAIR) images of patients breathing 100% oxygen1,2 and linked T1 quantification to O2 partial pressure in the CSF3,4. Dissolved O2 shortens T1 of water due to its paramagnetic properties. Because of its extremely long T2, selective CSF imaging can be achieved by using extremely long TE (>500ms) Spin-Echo based acquisitions, removing tissue signal contribution. Therefore, we report here a study using ultra long TE Fluid-Attenuated Inversion Recovery to image baseline CSF oxygenation with minimal tissue contribution.Methods

Theory: In Fast-Spin-Echo imaging, T1 can be simply estimated using a couple of acquisitions with and without using an inversion-recovery as shown below, assuming a perfect adiabatic inversion.$$\frac{M(IR_{on})}{M(IR_{off})}=\frac{1-2.\exp(-\frac{TI}{T_1})+\exp(-\frac{TR_{FSE}-TE_{last}}{T_1})}{1-\exp(-\frac{TR_{FSE}-TE_{last}}{T_1})}$$

With M(IRon) the signal in the CSF-suppressed image, M(IRoff) the signal in the unsuppressed image, TI the inversion time, TRFSE the FSE repetition time and TElast the total readout time.

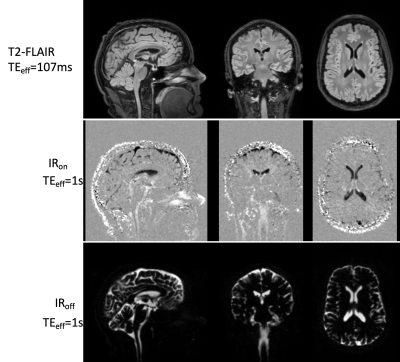

Experiments: Scans were performed at 3T (GE Signa Premier) using a 48-ch head coil. Six healthy volunteers (44±18yo) were recruited and divided in two groups (<35yo,N=3;>55yo,N=3).We acquired T2-FLAIR data (TI/TR/TE=1785/6000/107ms, variable flip-angles, ETL=220, linear view-ordering) as well as a pair of long TE acquisitions with and without inversion (IRon/IRoff) pulse using reversed-centric view-ordering, with 25 discarded echoes to avoid propagation of high-frequency features during early echoes, ETL=245, TR/TE=6/1s, first refocusing flip angle of 120 degrees followed by a gradual ramp down to 75 degrees5. TI was adjusted on a case by case depending on echo-train duration with a null target of T1=4.27s.Common parameters were: 136 sagittal slices, matrix=192x192 leading to (1.3mm)3 resolution, parallel imaging with 2x2 acceleration in both phase-encoded directions for an acquisition time of 3min21s per volume (total scan time 10min).

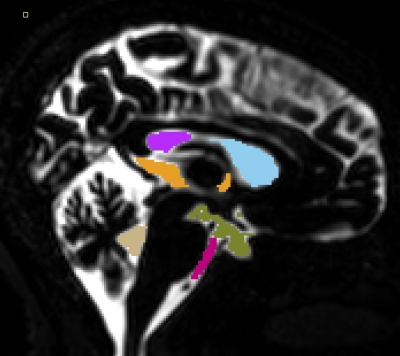

Analysis: Offline reconstruction of both IRon/IRoff volumes was performed to avoid losing sign changes information due to magnitude reconstruction. T1 quantification was then performed by calculating a ratio of the IR/non-IR volumes as described above. Co-registration of all data to the T2-FLAIR and segmentation of the CSF was performed using SPM12 on both T2-FLAIR and long-TE IRoff volumes to mask out parenchymal tissues that have very little signal at such long TE. Manual segmentation of the anterior/posterior lateral, third and fourth ventricles, as well as of the pontine and basal cisterns was performed as illustrated in Figure 1.

Results

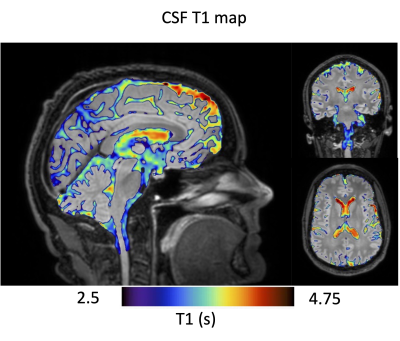

The long TE achieved good suppression of parenchymal tissues as shown in images of a representative subject (Figure 2) The real-valued IRon volume shows uneven CSF suppression across the brain and varying polarity suggesting longitudinal relaxation times both lower and higher than the target null. An individual T1 map overlaid on the conventional FLAIR is shown in Figure 3, visually showing heterogeneity of T1 distribution in the CSF.A one-way ANOVA showed a significant effect of the ROI (F=6.12, p<0.001) and age (F=4.92, p=0.03) on T1 suggesting regional but also age-related differences in CSF oxygenation. Post-hoc statistics (HSD Tukey-Kramer) show lower T1 in the cisterns (both pontine and basal) compared to lateral ventricles (p<0.04). The third ventricle also showed reduced T1 compared to the lateral ventricles (p<0.03).

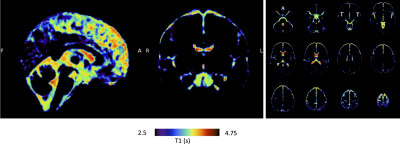

A group-averaged CSF T1 map is shown in Figure 4, reflecting some of the statistical observations, mainly the longer T1 encountered in the lateral ventricles compared to the basal and pontine cisterns. An interesting feature worth noting is a potential apparent T1 gradient in the lateral ventricles showing higher T1 values when moving anteriorly, which is however not reflected in the statistics.

Discussion and Conclusions

This work shows the possibility of CSF oxygenation imaging without tissue contamination using long TE T2-FLAIR, allowing, in a reasonable time, both qualitative and quantitative assessment using T1 mapping. Regional differences were measured showing the long T1 of the lateral ventricles while the basal and pontine cisterns around the basilar artery seem to have a consistently shorter T1. Caution should still be used as other confounders such as presence of proteins in CSF could also significantly modify longitudinal relaxation. While mechanisms of CSF oxygenation and its transport remain open questions, this shows the possibility of easily collecting an oxygenation sensitive measure. Studying potential modifications of CSF oxygenation in pathology could open new perspectives in neurofluids research.Acknowledgements

No acknowledgement found.References

1. Anzai, Y. et al. Paramagnetic Effect of Supplemental Oxygen on CSF Hyperintensity on Fluid-Attenuated Inversion Recovery MR Images. American Journal of Neuroradiology 25, 274–279 (2004).

2. Deliganis, A. V., Fisher, D. J., Lam, A. M. & Maravilla, K. R. Cerebrospinal Fluid Signal Intensity Increase on FLAIR MR Images in Patients under General Anesthesia: The Role of Supplemental O2. Radiology 218, 152–156 (2001).

3. Zaharchuk, G., Martin, A. J., Rosenthal, G., Manley, G. T. & Dillon, W. P. Measurement of cerebrospinal fluid oxygen partial pressure in humans using MRI. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine 54, 113–121 (2005).

4. Mehemed, T. M. et al. Dynamic Oxygen-Enhanced MRI of Cerebrospinal Fluid. PLOS ONE 9, e100723 (2014).

5. Alsop, D. C. The sensitivity of low flip angle RARE imaging. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine 37, 176–184 (1997).