3182

Effect of yawning on CSF and blood flow through the neck1Neuroscience Research Australia, Sydney, Australia

Synopsis

Keywords: Neurofluids, Neurofluids, Yawning, CSF

Despite being a common behaviour amongst many animals, research into the mechanics of yawning is limited. We have attempted to address this by performing sagittal real time scans and phase contrast scans to observe the flow of cerebrospinal fluid and blood through the midplane of the C3 vertebra of the spine during induced yawning. We found that over the course of a yawn venous flow and CSF flow both moved caudally during inspiration and rostrally during expiration.Introduction

Research into yawning has received little attention, despite being a common behaviour amongst most mammals, amphibians, reptiles1. Yawning also has the debatable distinction of being one of the least understood, yet frequent human behaviours2. Most yawns appear to be comprised of an initial deep inspiration, followed by a pause and then rapid expiration. Yet beyond simple characterisation, experimental data and investigation into the mechanics of yawning is limited3. The purpose of this study is to characterize the effect of respiration on the flow of neurofluids during yawning. By observing neurofluid movement through C3, using sagittal real time and phase contrast scans, we expect that the flow will be driven by differences between spinal and cranial pressures and not only a cranial fluid volume balance.Methods

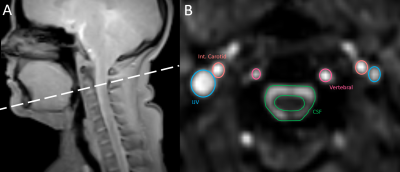

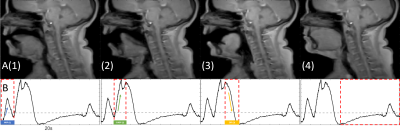

All participants in this study provided informed, written consent so that MRI data could be collected with a 3T Philips IngeniaTX scanner using a 32-channel head and neck coil. During the scans, the subjects were supine and shown video clips of people and animals yawning to induce contagious yawns. The scans collected included anatomical scans of the head-neck region, and real time phase contrast MRI scans to measure blood and CSF flow during yawning and quiet breathing using real-time-PC-MRI protocols. Respiratory motion was also recorded concurrently with the MRI scans using a respiratory monitoring band, placed on the sternum, which measured the displacement of the thorax.Acquisition. (i) The real-time PC-MRI protocol used (TFEPI) was not cardiac gated. Scanning parameters included: flip angle = 20o, matrix = 128x128mm, FOV = 192mm, repetition time (TR)/echo time (TE) = 13/7ms, and a slice thickness of 10mm. The scanning planes were positioned mid-C3, perpendicular to the spinal canal. The encoding velocities were set to 10-20cm/s for CSF flow measurements and 60-90 cm/s for arterial and internal jugular flow. To calculate flow rate, fluid velocities were integrated over regions of interest (ROI)4. The ROIs were manually drawn and tracked (Figure 1). (ii) RT sagittal scans of normal breathing and yawns were obtained using T1FFE. Scanning parameters included: matrix = 112x112, FOV = 220mm, repetition time (TR)/echo time (TE) = 4.1/2.3ms and a slice thickness of 10mm. A timelapse of a yawn is given in Figure 2.

Results

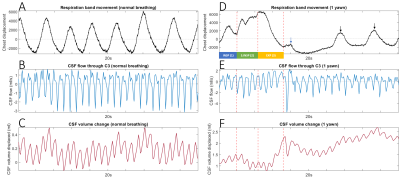

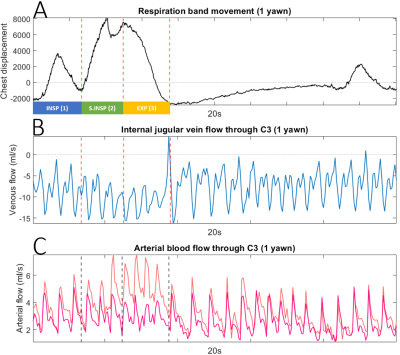

Figure 3 shows typical data obtained from the MRI scans and respiration band in a representative subject during periods of normal breathing and yawning. We collected data on CSF and blood flow (carotid and vertebral arteries and the internal jugular vein (IJV)). The most pronounced changes in neurofluid flow were noticed during the sharp inspiration, “gaping”, and sharp exhalation. To best explain the results, we have separated the mechanics of yawning into 4 periods as outlined in Figure 2.1. At the start of the yawn there was slight inspiration with no noticeable changes in neurofluid flow from that of normal breathing.

2. Sharp inspiration occurred at the same time as maximal opening of the mouth:

(i). During inspiration IJV flow increased, from a mean flow of -7.5ml/s to 11.58ml/s, while the pulsation amplitude decreased indicating caudal blood flow (Fig 4B).

(ii). CSF net flow moved caudally at the same time as venous drainage (Fig 3E). Consequently, total CSF volume decreased slightly.

3. Sharp expiration immediately followed with closing of the mouth.

(i). There was an increase in rostral CSF during exhalation compared to normal breathing (Fig 3B, E).

(ii). Total increase in CSF volume over the exhalation.

(iii). During the short gaping stage and first portion of exhalation, internal carotid blood flow increased markedly (34%) while vertebral blood flow remained the same (Fig 4C).

4. Breathing was paused for a short time and then returned to a normal breathing pattern and baseline neurofluid flow.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge this is the first study focusing on CSF and blood flow changes during yawning in humans. IJV and CSF flow were found to both move caudally during inspiration and rostrally during expiration. This result differs from the accepted view that during inspiration, CSF flows rostrally, due to negative intrathoracic pressure draining venous blood from the head, compensating for a decrease in cranial blood volume5. Our findings are in line with recent investigations into a holistic view of cranial and spinal respiratory CSF flow6, where cervical CSF flow directions during respiratory maneuvers (coughs and sniffs) depend on the difference between spinal and cranial pressures.Conclusion

Our results provide the first characterisation of neurofluid flow (CSF and blood) through the neck during yawning in humans. We found that during sharp yawning inspiration there was increased venous return to the heart and caudal CSF flow. During expiration, both venous and CSF flowed rostrally.Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the radiographer Brendan Moran, the NHMRC for providing financial support for this project (NHMRC Investigator Grant #APP1172988 (RG183247)), and the Australian Government for providing an RTP Scholarship.References

1. Baenninger, R. On yawning and its functions. Psychon Bull Rev 4, 198–207 (1997).

2. Konnikova, M. (2014). The surprising science of yawning. Retrieved from https://www.newyorker.com/science/maria-konnikova/the-surprising-science-of-yawning

3. Guggisberg, A. G., Mathis, J., Schnider, A., & Hess, C. W. (2010). Why do we yawn? Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 34, 1267-1276.

4. Heiberg E, Sjögren J, Ugander M, Carlsson M, Engblom H, Arheden H. Design and validation of Segment--freely available software for cardiovascular image analysis. BMC Med Imaging. 2010;10:1.

5. Dreha-Kulaczewski S, Konopka M, Joseph AA, et al. Respiration and the watershed of spinal CSF flow in humans. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):5594.

6. Lloyd RA, Butler JE, Gandevia SC, et al. Respiratory cerebrospinal fluid flow is driven by the thoracic and lumbar spinal pressures. J Physiol. 2020;598(24):5789-5805.

Figures