3179

Alterations of brain motion in idiopathic intracranial hypertension (IIH) based on amplified MRI (aMRI)1GE Healthcare, Gisborne, New Zealand, 2Auckland Bioengineering Institute, University of Auckland, Auckland, New Zealand, 3Mātai Medical Research Institute, Gisborne, New Zealand, 4Department of Opthalmology, University of Auckland, Auckland, New Zealand, 5Faculty of Medical and Health Sciences & Centre for Brain Research, University of Auckland, Auckland, New Zealand, 6Chelsea Hospital, Gisborne, New Zealand, 7Department of Anatomy & Medical Imaging, Faculty of Medical and Health Sciences, Centre for Brain Research, University of Auckland, Auckland, New Zealand, 8Eye Institute, Auckland, New Zealand, 9Department of Physiology, Faculty of Medical and Health Sciences, University of Auckland, Auckland, New Zealand

Synopsis

Keywords: Neurofluids, Brain, IIH, Intracranial Pressure

Heartbeat-driven brain motion has historically remained limited to the domain of research. Such motion may provide a window to characterise parenchymal and CSF pressures where direct, invasive measurements are disruptive and difficult to justify. Amplified MRI (aMRI) is a recently developed method which amplifies subtle brain motion. We show preliminary data that aMRI can be used to detect changes in brain motion associated with increased intracranial pressure in idiopathic intracranial hypertension (IIH), suggesting a potential non-invasive method for evaluating pressure levels of the subarachnoid space in patients with altered intracranial pressure.Introduction

There is a significant clinical need for non-invasive measures of raised intracranial pressure (ICP). Raised ICP, or intracranial hypertension, is a common problem in neurosurgical and neurological practice1-5. The consequences of raised ICP are compromised brain perfusion, oxygenation, and brain ischemia6 and if left untreated it can lead to brain injury, blindness, seizure, coma, stroke, or death. Clinical management is hampered by the lack of a reliable, non-invasive technique to determine if ICP is elevated – a suspected diagnosis of intracranial hypertension can only be confidently confirmed by invasive measurement. Causes of increased ICP may include decreased CSF outflow, decreased size of the cranial vault, increased CSF production, or increased intracranial tissue volume.Our hypothesis is that pulsatile brain motion will be predictably and proportionally altered by changes in the level of ICP. The rationale is that this motion is strongly determined by brain compliance, which is affected by blood perfusion and ICP. Amplified MRI7-10 has improved our ability to rapidly inspect these brain motions. In this study, we apply aMRI pre- and post-lumbar puncture in IIH to explore whether brain motion patterns are altered. If cardiac-linked brain motion shifts can be detected, this has the potential to allow for the non-invasive measurement of ICP.

Methods

Human participants: Under ethical approval, 6 IIH patients (all female, average age 30.6±10.6 years) were recruited from neuro-ophthalmology clinics if IIH was suspected. Patients underwent a baseline MRI scan, followed by a lumbar puncture (LP). LP was also used to drain CSF and temporarily lower ICP to a normal level. These patients underwent a repeat MRI within 4 hours of LP.

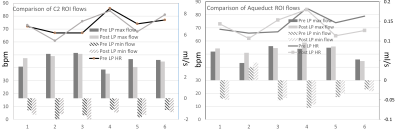

Image Acquisition: Scans were acquired on a 3T MRI scanner (GE SIGNA Premier; General Electric, MI, USA; AIRTM 48-channel head coil). Cine 3D bSSFP [11] (the base acquisition for aMRI, resolution 1mm isotropic, 2min scan time, 160 slices), along with other conventional sequences (combined scan time of ~30 min) were acquired at baseline and post-LP. 2D Phase Contrast (PC-)MR images were acquired at the aqueduct and C2 spinal cord levels (venc=9 cm/s, resolution=1.2 x 1.2 x 4.0mm).

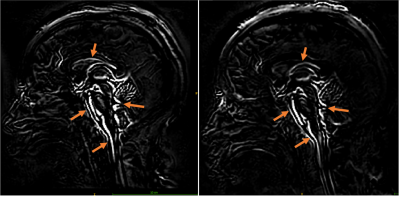

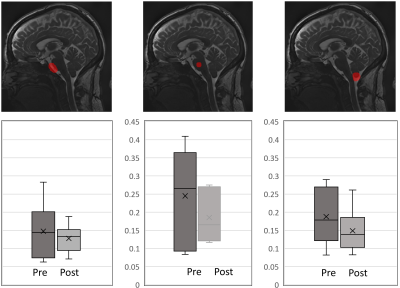

Data Visualisation and Analysis: The cine bSSFP data was amplified with a global amplification factor of x40, and difference maps were calculated across the cardiac frames by subtracting each cardiac frame from the first frame (Fig. 2). The first frame of the cardiac cycle was used as the reference for calculating displacement maps using the Demons registration tool in Matlab(R). For all subjects, ROI seeds were manually placed in the pons, prepontine cistern-pons, and tonsil-cisterna magna (Fig. 3). For each ROI, the average displacement within one cardiac cycle was reported.

Results

All patients had elevated opening pressure (median, 30 cm water) decreased by the removal of CSF to a median closing pressure of 20 cm water. Reduced ICP was found to alter patterns of brain tissue motion (Fig. 1-2). For subject 4 and 6, visual assessment showed that brain motion was not detectable and hence amplification was iteratively increased up to x80. The maximum difference map in the mid-sagittal plane in Fig. 1 shows regions where the edge (of CSF-tissue boundary) motion can be detected, providing a visualization of the regions where motion resulted in significant changes in pixel intensity. These include the lateral ventricular spaces, fourth ventricular spaces, prepontine cistern, and brain stem as shown by arrows. The average displacement was extracted in three regions. Larger variability in brain motion (Fig. 3) was observed in pre-LP regions compared to post-LP. Positive CSF flow measured at C2 decreased in post-LP.Discussion

In this preliminary study, patterns of brain motion were altered based on aMRI acquired pre- and post- lumbar puncture in IIH patients, which could provide a non-invasive window into the material properties of the parenchyma and pressure levels in the subarachnoid space. Coupled with biomechanical modelling that accounts for blood and CSF dynamics, such cardiac-linked brain motion has the potential to allow for the non-invasive measurement of ICP.Previous studies have examined the link between elevated ICP and brain tissue motion. Saindaine et al.12 used DENSE MRI13 to compare the brain tissue motion in patients with chronically elevated ICP before and after LP. In our cohort, we observed similar behavior for subjects 4 and 6 only. While providing an important basis for estimating ICP, current models treat the entire brain as a homogeneous unit and are not able to account for regional or temporal variations in actual tissue compliance14. Our preliminary data from aMRI indicate regional variations in tissue displacement (and hence in regional elastance). Using aMRI, our future studies hope to move beyond a lumped model of cerebral elastance and incorporate metrics of tissue displacement into the model to account for regional effects which we hypothesise are important for a more accurate ICP measurements.

Conclusion

aMRI can detect changes in cardiac-driven brain tissue pulsations that arise due to changes in ICP in IIH patients. Further work will involve drawing insight into the mechanisms underlying this behaviour through the analysis of angiographies and hemodynamic imaging that captures blood and CSF dynamics.Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Royal Society of New Zealand Marsden Fund, and the Kānoa - Regional Economic Development & Investment Unit, New Zealand. We are grateful to Professor Richard Buxton for his mentorship on this project, Mātai Ngā Māngai Māori for their cultural guidance, and to our research participants for dedicating their time toward this study. We would like to acknowledge the support of GE Healthcare.

References

1. Wall M. Update on Idiopathic Intracranial Hypertension. Neurol Clin. 2017;35:45–57.

2. Frič R, Pripp AH, Eide PK. Cardiovascular risk factors in Chiari malformation and idiopathic intracranial hypertension. Brain Behav. 2017;7:e00677.

3. Eide PK, Pripp AH. The prevalence of cardiovascular disease in non-communicating hydrocephalus. Clinical Neurology and Neurosurgery. 2016;33–38.

4. Hoffmann J, Mollan SP, Paemeleire K, Lampl C, Jensen RH, Sinclair AJ. European headache federation guideline on idiopathic intracranial hypertension. J Headache Pain. 2018;19:93.

5. Hawthorne C, Piper I. Monitoring of Intracranial Pressure in Patients with Traumatic Brain Injury. Frontiers in Neurology. 2014.

6. Capizzi A, Woo J, Verduzco-Gutierrez M. Traumatic Brain Injury: An Overview of Epidemiology, Pathophysiology, and Medical Management. Med Clin North Am. 2020;104:213-238.

7. Holdsworth SJ, Rahimi MS, Ni, WW, Zaharchuk G, & Moseley ME, Amplified magnetic resonance imaging (aMRI). Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 75(6):2245–2254.

8. Terem I, Ni WW, Goubran M, Rahimi MS, Zaharchuk G, Yeom KW, Moseley ME, Kurt M & Holdsworth SJ. Revealing sub-voxel motions of brain tissue using phase-based amplified MRI (aMRI). Magnetic Resonance in Medicine 2016;80(6):2549–2559.

9. Terem I, Dang L, Champagne A, Abderezaei J, Pionteck A, Almadan Z, Lydon AM, Kurt M, Scadeng M, Holdsworth SJ. 3D amplified MRI (aMRI). Magnetic Resonance in Medicine 2021;86(3): p1674–1686.

12. Saindane AM, Qiu D, Oshinski JN, Newman NJ, Biousse V, Bruce BB, Holbrook JF, Dale BM, Zhong X. Noninvasive Assessment of Intracranial Pressure Status in Idiopathic Intracranial Hypertension Using Displacement Encoding with Stimulated Echoes (DENSE) MRI: A Prospective Patient Study with Contemporaneous CSF Pressure Correlation. American Journal of Neuroradiology. 2018;39(2):311–316.

10. Abderezaei J, Pionteck A, Terem I, Dang L, Scadeng M, Morgenstern P, Shrivastava R, Holdsworth SJ, Yang Y, Kurt M. Development, calibration, and testing of 3D amplified MRI (aMRI) for the quantification of intrinsic brain motion. Brain Multiphysics. 2021:100022.

11. Poncelet BP, Wedeen VJ, Weisskoff RM, Cohen MS. Brain parenchyma motion: Measurement with cine echo-planar MR imaging. Radiology. 1992;185(3):645–651.

12. Saindane AM, Qiu D, Oshinski JN, Newman NJ, Biousse V, Bruce BB, Holbrook JF, Dale BM, Zhong X. Noninvasive Assessment of Intracranial Pressure Status in Idiopathic Intracranial Hypertension Using Displacement Encoding with Stimulated Echoes (DENSE) MRI: A Prospective Patient Study with Contemporaneous CSF Pressure Correlation. American Journal of Neuroradiology. 2018;39(2):311–316.

13. Soellinger M, Rutz AK, Kozerke S, Boesiger P. 3D cine displacement-encoded MRI of pulsatile brain motion. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2009;61(1):153–162.

14. Alperin NJ, Lee SH, Loth F, Raksin PB, Lichtor T. MR-Intracranial Pressure (ICP): A Method to Measure Intracranial Elastance and Pressure Noninvasively by Means of MR Imaging: Baboon and Human Study. Radiology. 2000;217(3):877–885.

Figures