3177

Effects of Noise on Blood-Brain Barrier Permeability Measurement Error in Diffusion Weighted and Multi-Echo Arterial Spin Labeling MRI1Biomedical Engineering, University of California, Davis, Davis, CA, United States, 2Radiology, University of California, Davis, Davis, CA, United States, 3Neurology, University of California, Davis, Davis, CA, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Neurofluids, Arterial spin labelling, Blood-Brain Barrier

Arterial spin labeling (ASL) MRI is noninvasive and has the potential to become a sensitive, clinically useful way to measure blood-brain barrier (BBB) permeability. Here, we focused on two different ASL sequences, diffusion-weighted (DW) and multi-echo (T2), and performed simulations to compare the robustness of BBB permeability (Texch) measurement to different levels of noise. We conclude that the Texch fitting for DW ASL is more robust to noise at a physiological arterial transit time (ATT) of 1000ms at the expense of being more vulnerable to bias when the assumed ATT deviates from the true underlying ATT.Introduction

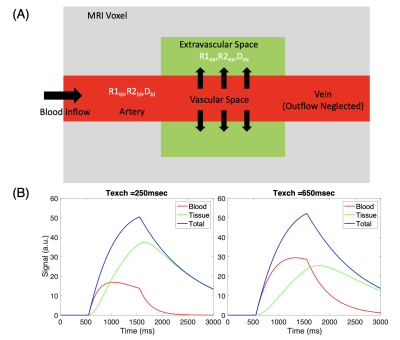

Arterial spin labeling (ASL) MRI has emerged as a popular method to assess blood-brain barrier (BBB) permeability. Diffusion-weighted (DW) and multi-echo (T2) are two ASL methods that can probe BBB permeability. Both rely on the different diffusivity and T2 times, respectively, of brain tissue and blood to partition the overall ASL signal within a voxel into an intravascular and extravascular component (Figure 1). This theoretical two-compartment model [1] enables the incorporation of an exchange constant (Texch) that can be considered a proxy for BBB integrity and can be quantified in both DW- and multi-T2 ASL. [2-4]Thus, our study sought to simulate the different, but analogous, Texch quantification steps for DW and multi-T2 ASL and to determine which one was more robust to various levels of Gaussian noise. We performed these simulations because low signal-to-noise ratios (SNRs) have been a major weakness of ASL MRI. Our simulated results will inform future studies measuring BBB permeability utilizing these two methods in clinical applications.

Methods

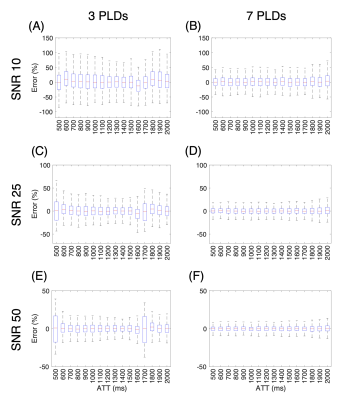

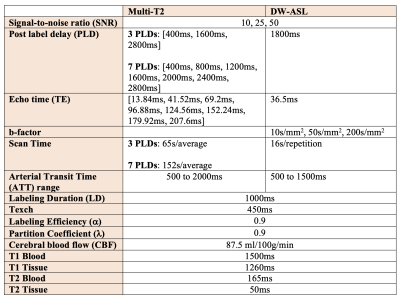

In multi-T2 ASL, the signal is sampled at multiple post-label delays (PLDs) and echo times (TEs), while in DW ASL, it is sampled at a single PLD and TE. [4-6] To generate the multi-T2 ASL signal, we ran the simulations with 3 and 7 PLDs (Table 1) to account for Hadamard encoding and with 8 TEs as reported by Mahroo et al [5] at a range of arterial transit times (ATTs). To generate the DW ASL signal, we simulated scalar vascular signal fractions (A1s) at 3 different b-factors (Table 1) using an empirically derived biexponential fitting equation reported by Shao et al [3] at a PLD of 1800ms for a range of ATTs.After we generated the different ASL signals, we ran Monte Carlo simulations with each of the 1000 iterations adding Gaussian noise using the randn function in MATLAB at a SNR of 10, 25, and 50. The noise variance was set as the peak ASL signal magnitude divided by the SNR. For multi-T2 ASL simulation, the fminsearch function was used to fit the ASL general kinetic model [7] to ASL signals planes with added noise to extract a fitted $$$\hat ATT$$$ and $$$\hat Texch$$$. The extracted $$$\hat Texch$$$ was then compared to the true underlying Texch of 450ms to calculate the error at each ATT (Figure 2).

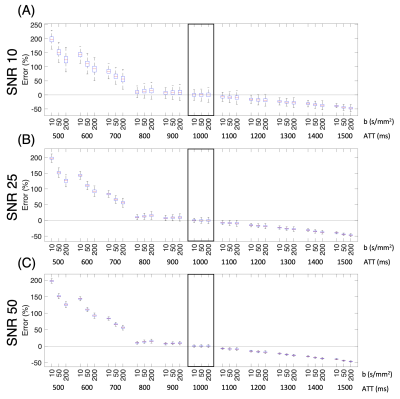

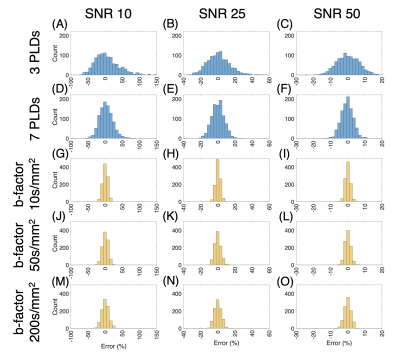

For DW ASL simulations, a fitted $$$\hat Texch$$$ was extracted using the fzero function from the DW theoretical equations also derived from the general kinetic model [6, 7]. The Texch error for a range of “true” ATTs was calculated by comparing the $$$\hat Texch$$$ to the reference Texch of 450ms at a “fixed” ATT of 1000ms (Figure 3). Finally, we generated histograms comparing Texch error for both multi-T2 and DW ASL simulations at an ATT of 1000ms (Figure 4). All outliers, defined as a value more than three scaled median absolute deviations (MAD) from the median, were omitted.

Results and Discussion

In Figure 2, we can see that sampling at 7 PLDs results in lower Texch fitting errors across a range of ATTs as compared to sampling at 3 PLDs at the expense of a longer scan time of 152 seconds versus 65 seconds, respectively. The lower error distribution is expected because sampling at 7 PLDs provides more than twice the data points to fit the ASL theoretical equations compared to sampling at 3 PLDs. Another trend is that, for the 3 PLD case at the highest SNR of 50, ATTs, specifically 500ms and 1700ms, just slightly higher than a PLD time do not experience the error reduction benefits of an increased SNR (Figure 2E). An explanation is that when the ATT exceeds a PLD time, that PLD time fails to capture the later arriving kinetic curve.In Figure 3, we choose to run the DW simulations with a b-factor of 50s/mm2 consistent with the protocol reported by Shao et al [3] as well as with 10s/mm2 and 200s/mm2 to observe trends at extreme b-factors. The errors across a range of true ATTs are quantified about the Texch calculated at a reference ATT of 1000ms. Figure 3 shows that the b-factor becomes more important when the estimated ATT does not reflect the true ATT. Additionally, at lower SNRs, our results suggest that a smaller b-factor, which suppresses less of the vascular signal, generates a lower error distribution at the reference ATT of 1000ms.

Finally, Figure 4 summarizes the error distribution in a histogram. The analysis is done at an ATT of 1000ms for both ASL simulations. In general, DW ASL exhibits lower error distributions compared to its multi-T2 counterpart. However, we must consider that DW ASL is a slightly more complicated method with an optimization step before the Texch quantification scan and can have a large bias if there is a discrepancy between the assumed and actual ATT, as shown in Figure 3. Future simulations analyzing Texch error should equalize the scan times between the two methods and use the number of multi-T2 averages and DW repetitions associated with that scan time.

Acknowledgements

R00-NS102884References

1. Parkes, L.M. and P.S. Tofts, Improved accuracy of human cerebral blood perfusion measurements using arterial spin labeling: accounting for capillary water permeability. Magn Reson Med, 2002. 48(1): p. 27-41.

2. Dickie, B.R., G.J.M. Parker, and L.M. Parkes, Measuring water exchange across the blood-brain barrier using MRI. Prog Nucl Magn Reson Spectrosc, 2020. 116: p. 19-39.

3. Shao, X., et al., Mapping water exchange across the blood-brain barrier using 3D diffusion-prepared arterial spin labeled perfusion MRI. Magn Reson Med, 2019. 81(5): p. 3065-3079.

4. Gregori, J., et al., T2-based arterial spin labeling measurements of blood to tissue water transfer in human brain. J Magn Reson Imaging, 2013. 37(2): p. 332-42.

5. Mahroo, A., et al., Robust Multi-TE ASL-Based Blood-Brain Barrier Integrity Measurements. Front Neurosci, 2021. 15: p. 719676.

6. St Lawrence, K.S., D. Owen, and D.J. Wang, A two-stage approach for measuring vascular water exchange and arterial transit time by diffusion-weighted perfusion MRI. Magn Reson Med, 2012. 67(5): p. 1275-84.

7. Buxton, R.B., et al., A General Kinetic Model for Quantitative Perfusion Imaging with Arterial Spin Labeling. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine, 1998.

Figures