3176

Respiratory Modulation of Cerebrospinal Fluid Flow During Paced Breathing1Neuroscience, Boston University, Boston, MA, United States, 2Massachusetts General Hospital, Athinoula A. Martinos Center for Biomedical Imaging, Charlestown, MA, United States, 3Department of Radiology, Harvard Medical School, Charlestown, MA, United States, 4Biomedical Engineering, Boston University, Boston, MA, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Neurofluids, Neurofluids, Cerebrospinal Fluid, CSF

We used flow-sensitive fMRI to explore the effect of paced respiration on cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) flow. Results indicate that paced breathing tasks at rates between 0.1 Hz and 0.25 Hz increase CSF flow. All breathing paces showed a striking increase in CSF inflow-enhanced signals with the highest group-averaged amplitude being 26% during the 0.1 Hz breathing task. We conclude that diaphragmatic paced breathing is an effective modulator of CSF flow that may represent increased fluid transport relative to free breathing.INTRODUCTION:

Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) is the primary medium for brain waste clearance mechanisms of the glymphatic system1. In awake humans, CSF flow is driven by respiratory pressures and increases following periods of physical activity2,3,4,5. During NREM sleep, when the glymphatic transport is thought to be enhanced, large fluctuations in fourth ventricle CSF flow are anticorrelated with grey matter hemodynamic activity6. Respiratory frequencies change across arousal states, which may contribute to modulating CSF flow, but the effect of different breathing paces on CSF flow has not yet been directly tested. To understand how different respiratory frequencies drive CSF flow independent of arousal state, we measured flow signals in the fourth ventricle using fast fMRI while subjects performed a visually guided paced breathing task, at a range of paces spanning the typical rates that occur in different states of arousal.METHODS:

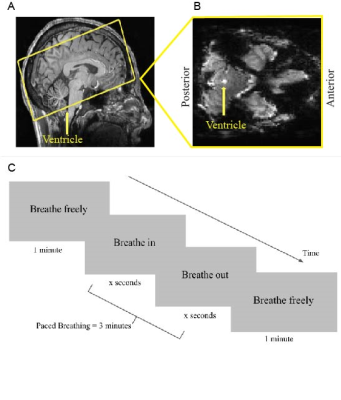

Seven subjects gave informed consent and were scanned on a 7T Siemens whole-body scanner with a custom-built 64-channel head coil array. Subjects completed 30 minutes of guided diaphragmatic breathing before the scan to practice minimizing motion and achieving stable breath cycles. Each session began with a 0.75 mm isotropic multi-echo MPRAGE. Functional runs were acquired using a single-shot gradient-echo SMS-EPI with 2 mm isotropic resolution (R=2 acceleration, MultiBand factor=4, TR=499 ms, TE=24 ms, echo-spacing=0.59 ms, flip angle=40°). The bottom edge of the acquisition volume was placed perpendicular to the base of the fourth ventricle, in order to measure CSF inflow signals due to flow-related enhancement (Fig 1a,b) 6,7. Stimuli consisted of a visual prompt programmed in MATLAB that guided subjects through five-minute breathing tasks. All scans started with a 5-minute baseline run guided by a prompt displaying “Breathe Normally”. Subsequent runs consisted of 1 minute of free breathing, 3 minutes of paced breathing, and then 1 minute of free breathing. The paced breathing was performed at either 0.25 Hz, 0.17 Hz, 0.125 Hz, or 0.1 Hz, guided by prompts labeled “Breathe In” and “Breathe Out” (Fig 1b). Respiratory and heart rate data were collected using a respiratory belt and pulse oximeter to confirm that subjects followed the task. Data were slice-timing corrected and CSF signals were extracted from the flow-related enhancement signal within the fourth ventricle. Oscillatory CSF responses to the breathing task were computed by binning the CSF time course by the breath cycle and averaging all cycles for a given pace. Group averages for respiratory-locked CSF flow were calculated using the 15th percentile of the binned CSF time course as baseline, approximating a no-flow baseline. Statistical tests were calculated using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test.RESULTS:

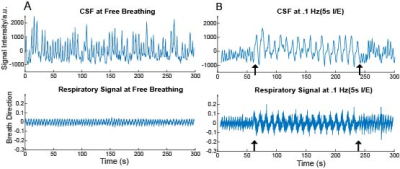

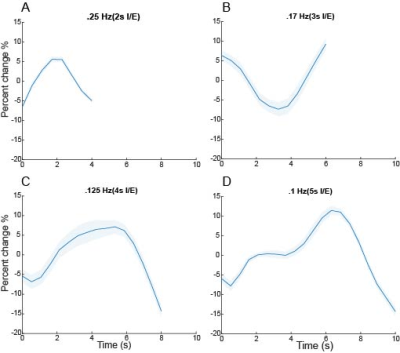

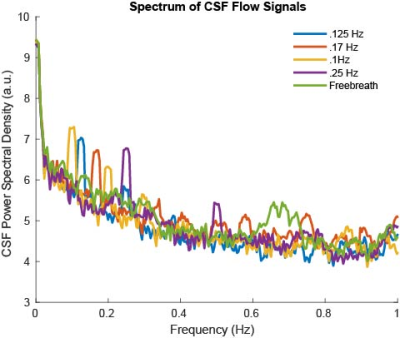

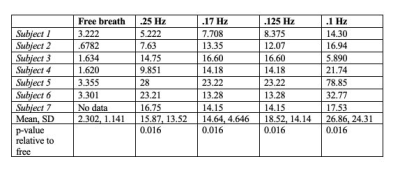

We observed oscillatory coupling between the CSF signal intensity and respiratory trace, validating the previous literature on the modulation of CSF flow by respiration (Fig 2a,b). The black arrows in Fig 2b highlight the distinct differences in CSF flow signal intensity amplitude during the 0.1 Hz breathing task, relative to free breathing epochs before and after the task. Clear breath-locked CSF flow was observed at each breathing frequency (Fig 3). Power spectra showed strong induction of oscillatory CSF flow at the respiratory frequency, and power was highest for the slowest pace, the 0.1 Hz condition (Fig 4). We found that each paced frequency induced strong CSF flow, relative to the free breathing condition (p<0.05 for each pace, relative to free breathing) (Fig 5).DISCUSSION:

We found that CSF flow during various paced breathing frequencies was strongly driven by the respiratory cycle. As seen in Fig. 3, all paced breathing traces show a peak or trough at the midpoint of the breath cycle indicating the shift from inhale to exhale is modulating this signal change. It is also likely that CSF flow differences arise from changes in breathing depth, as slower paces also allow for deeper breaths. Paced breathing at 0.1Hz had the highest amplitude in the power spectrum around 0.1Hz, suggesting it was particularly effective at modulating CSF flow. Breath cycles at 0.1Hz are hypothesized to have a heightened capacity for autonomic entrainment and will be further explored as a pace of interest for increasing physiological synchrony8. All paces had a higher power peak at their respective frequencies than free breathing across the entire spectrum highlighting the modulatory influence of paced breathing on CSF flow.CONCLUSION:

Here we show that CSF flow can be enhanced relative to free breathing using different rhythmic breathing paces. This finding suggests future work could explore how breath training can be used as a modulator of CSF flow. The accessible nature of the approach may be particularly relevant to people from a diverse range of socioeconomic backgrounds, and individuals with disordered sleep, by providing a noninvasive modulator of brain fluid dynamics.Acknowledgements

This work was funded by NIH R01-AT011429, P41-EB030006, the Simons Collaboration on Plasticity in the Aging Brain (no. 811231), the Sloan Fellowship, the 1907 Trailblazer Award, and was made possible by the resources provided by Shared Instrumentation Grant S10-OD023637.References

REFERENCES:

1. Xie L, Kang H, Xu Q, Chen MJ, et al. Sleep drives metabolite clearance from the adult brain. Science. 2013 Oct;342(6156):373-7.

2. Tarumi T, Yamabe T, Fukuie M, et al. Brain blood and cerebrospinal fluid flow dynamics during rhythmic handgrip exercise in young healthy men and women. J Physiol. 2021 Mar;599(6):1799-1813.

3. Feinberg D.A., Mark A.S. Human brain motion and cerebrospinal fluid circulation demonstrated with MR velocity imaging. Radiology. 1987;163:793–799.

4. Dreha-Kulaczewski, S, Joseph A., A, Merboldt, K, et al., Inspiration is the Major Regulator of Human CSF. J Neuroscience. 2015 Feb; 35(6):2485-2491

5. Aktas, G., Kollmeier, J.M., Joseph, A.A. et al. Spinal CSF flow in response to forced thoracic and abdominal respiration. Fluids Barriers CNS. 2019. 16, 10

6. Fultz NE, Bonmassar G, Setsompop K, Stickgold RA, Rosen BR, Polimeni JR, LewisLD. Coupled electrophysiological, hemodynamic, and cerebrospinal fluid oscillations in human sleep. Science. 2019 Nov 1;366(6465):628-631.

7. J. H. Gao, I. Miller, S. Lai, J. Xiong, P. T. Fox, Quantitative assessment of blood inflow effects in functional MRI signals. Magn. Reson. Med. 1996 36, 314–319

8. Noble, D. J., & Hochman, S. Hypothesis: Pulmonary afferent activity patterns during slow, deep breathing contribute to the neural induction of physiological relaxation. Frontiers in Physiology, 2019, 10.

Figures