3171

Probing metabolites in antiretroviral and nicotine treated mouse brains using MRS and CEST-MRI

Gabriel Gauthier1, Aditya Bade1, and Yutong Liu1

1University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, NE, United States

1University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, NE, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: CEST & MT, CEST & MT, MRI, MRS, HIV, Antiretroviral, nicotine, glutamate, myo-inositol, choline

To better understand synergistic effects of antiretroviral drugs (ARV) and nicotine on neuroimmune functions, we observed drug-associated metabolites in mice utilizing CEST MRI and MRS. Increased CEST signal was found at 3.5 ppm suggesting increased glutamate in mice treated with nicotine. MRS results showed increased myo-inositol in both ARV and nicotine treated mice. glutamate is an excitatory neurotransmitter and myo-inositol is a biomarker of glial activation. The imaging results suggested elevated neuronal activation and neuroimmune dysfunction.Introduction

The Chemical Exchange Saturation Transfer (CEST) effect is characterized by the exchange of spin saturation from compounds with liable hydroxyl, amine, and amide protons to those of adjacent water molecules.[1] This effect is now being used as a novel Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) contrast agent, in a technique known as CEST-MRI.[1-4] With this modality, it is now possible to probe the body in vivo for compounds of interest (including many key metabolites and drugs) that exist in previously unobservable locations and concentrations.[1-4] In our investigation, we used CEST-MRI to study metabolic alterations in the central nervous system (CNS) of mice administrated with antiretroviral drugs (ARV) and nicotine, with emphasis on the hippocampus (HIP) and cortex (CTX) regions. We then evaluated the metabolic content of these regions via magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS), a mature technique, in an attempt to correlate the two modalities.Methods

Sixteen C57BL/6 mice (male, 8 weeks) were divided into four groups of four. Group 1 was given a combinational ARVs (Dolutegravir (DTG, 51.25 mg/kg/day), Lamivudine (3TC, 250 mg/kg/day), and Abacavir (ABC, 500 mg/kg/day)) for 12 days via oral gavage. Group 2 was given nicotine (2 mg/kg/day in 100 uL saline) through i.p. injection for 12 days. Group 3 was administrated with both ARVs and nicotine at the same dosages as the previous groups. Group 4 was administrated with the drug vehicle alone and was used as control. CEST-MRI was performed on a 7 T scanner (Bruker BioSpec, Billerica, MA) with a volume coil for RF transmission and a 4-element array coil for reception. For each scan, data was collected using the RARE sequence, with offsets ranging from -5 to +5 ppm, divided into steps of 0.2 ppm, and utilizing an RF power of 2 uT, and duration of 1 second. CEST data was fitted using 5-pool Lorentzian functions, as demonstrated in a previous study.[5] MRS data was processed using LCModel fitting, as seen in numerous other studies. To evaluate trends in metabolite distributions, Student’s t-test was used to compare all pairs of dosing groups, with a target p-value of ≤ 0.05.Results

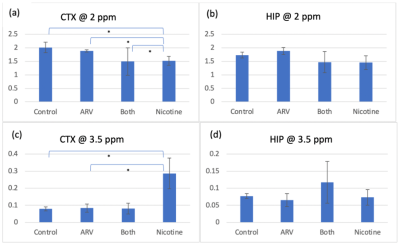

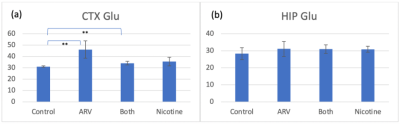

CEST @ 2 ppm, shown in Figure 1ab, indicates that nicotine-only mice experience a significant CTX signal decrease compared to control (p=0.032), ARV-only (p=0.037), and ARV+nicotine (p=0.037) mice, with no distinction in the HIP. CEST @ 3.5 ppm, shown in Figure 1cd, indicates that nicotine-only mice experienced significant CTX signal increase compared to control (p=0.050) and ARV-only (p=0.040) mice, with no distinction on the HIP.Glutamate MRS, shown in Figure 2, found no significant distinction in either region, but suggested a trend of increase on the CTX in ARV (p=0.061) and ARV+nicotine (p=0.076) groups when compared with controls.

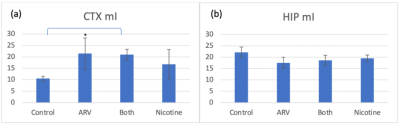

Myo-inositol MRS, shown in Figure 3, shows a significant increase on the CTX in ARV+nicotine mice (p=0.008) when compared to controls, but showed no difference in the HIP.

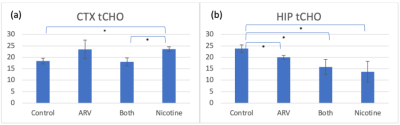

Finally, tCHO MRS, shown in Figure 4, indicates a significant increase on the CTX in nicotine-treated mice when compared with control (p=0.013) and ARV+nicotine (p=0.023) mice. The tCHO signal decreased on the HIP in ARV (p=0.042), nicotine (p = 0.040), and ARV+nicotine (p=0.036) mice.

Discussion

Expanding upon nicotine’s well-documented immunocompromising and neuroinflammatory properties[6-8], growing evidence suggests ARVs and nicotine induce a form of mutual metabolic modulation: nicotine can cause altered metabolism of ARVs, altering their pharmokinetics (PK), while ARVs can lead to variable metabolism of nicotine.[9-17] This feedback loop may result in highly variable drug efficacy for a regime that requires consistency. Noting the high incidence of nicotine usage in people living with HIV (PLWH),[18] the nicotine-related metabolite glutamate’s crucial role in healthy CNS function, and the troublesome pervasiveness of HIV-associated neurological disorders (HAND) for PLWH[19], the described study aimed to monitor interactions between ARVs and nicotine with CEST-MRI.The signal increase @ 3.5 ppm present in nicotine-dosed groups suggests that glutamate is significantly affected. Glutamate is an excitatory neurotransmitter. Our CEST MRI results suggested that nicotine results in increased neuronal activity and glutamate release. Myo-inositol is a biomarker of glial activation. Our MRS results showed both ARVs and nicotine caused glial activation.

Curiously, comparing modalities yields seemingly contradictory results. Given that glutamate CEST relies upon the detection of amine protons @3.5 ppm, a significant increase in cortex should imply increased glutamate; this was not observed in MRS. We believe this discrepancy may stem from MRS offering lower overall sensitivity than CEST, as well as “crowding” of multiple metabolites around the frequency offsets of interest. Nevertheless, we demonstrated synergistic effects of ARVs and nicotine on the CNS in mice using CEST MRI and MRS. The technique can be further developed to study the neurotoxicity of ARVs in the context of substance abuse.

Acknowledgements

The authors would thank UNMC Bioimaging (MRI) core facility for the help on data acquisition and processing. The study was partially supported by NIH R21MH128123, U54GM115458, R01MH121402, R21HD106842, P30GM127200, P20GM130447, and Nebraska Research Initiative.References

- Ward KM, Aletras AH, Balaban RS. A New Class of Contrast Agents for MRI Based on Proton Chemical Exchange Dependent Saturation Transfer (CEST). Journal of Magnetic Resonance 2000; 143(1):79-87.

- van Zijl PC, Yadav NN. Chemical exchange saturation transfer (CEST): what is in a name and what isn't? Magnetic resonance in medicine 2011; 65(4):927-948.

- Liu G, Song X, Chan KW, McMahon MT. Nuts and bolts of chemical exchange saturation transfer MRI. NMR Biomed. 2013 Jul;26(7):810-28. doi: 10.1002/nbm.2899. Epub 2013 Jan 10. PMID: 23303716; PMCID: PMC4144273.

- Wu B, Warnock G, Zaiss M, Lin C, Chen M, Zhou Z, et al. An overview of CEST MRI for non-MR physicists. EJNMMI physics 2016; 3(1):19.

- Bade AN, Gendelman HE, McMillan J, Liu Y. Chemical exchange saturation transfer for detection of antiretroviral drugs in brain tissue. Aids 2021; 35(11):1733-1741.

- Vassallo R, Kroening PR, Parambil J, Kita H. Nicotine and oxidative cigarette smoke constituents induce immune-modulatory and pro-inflammatory dendritic cell responses. Mol Immunol 2008; 45(12):3321-3329.

- Vassallo R, Tamada K, Lau JS, Kroening PR, Chen L. Cigarette smoke extract suppresses human dendritic cell function leading to preferential induction of Th-2 priming. J Immunol 2005; 175(4):2684-2691.

- Yanagita M, Kobayashi R, Kojima Y, Mori K, Murakami S. Nicotine modulates the immunological function of dendritic cells through peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma upregulation. Cell Immunol 2012; 274(1-2):26-33.

- Durazzo TC, Rothlind JC, Cardenas VA, Studholme C, Weiner MW, Meyerhoff DJ. Chronic cigarette smoking and heavy drinking in human immunodeficiency virus: consequences for neurocognition and brain morphology. Alcohol 2007; 41(7):489-501.

- Liang H, Chang L, Chen R, Oishi K, Ernst T. Independent and Combined Effects of Chronic HIV-Infection and Tobacco Smoking on Brain Microstructure. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol 2018; 13(4):509-522.

- Earla R, Ande A, McArthur C, Kumar A, Kumar S. Enhanced nicotine metabolism in HIV-1-positive smokers compared with HIV-negative smokers: simultaneous determination of nicotine and its four metabolites in their plasma using a simple and sensitive electrospray ionization liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry technique. Drug Metab Dispos 2014; 42(2):282-293.

- Schnoll RA, Thompson M, Serrano K, Leone F, Metzger D, Frank I, et al. Brief Report: Rate of Nicotine Metabolism and Tobacco Use Among Persons With HIV: Implications for Treatment and Research. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2019; 80(2):e36-e40.

- Ekins S, Mathews P, Saito EK, Diaz N, Naylor D, Chung J, et al. alpha7-Nicotinic acetylcholine receptor inhibition by indinavir: implications for cognitive dysfunction in treated HIV disease. AIDS 2017; 31(8):1083-1089.

- Kumar S, Rao PS, Earla R, Kumar A. Drug-drug interactions between anti-retroviral therapies and drugs of abuse in HIV systems. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol 2015; 11(3):343-355.

- Ghura S, Gross R, Jordan-Sciutto K, Dubroff J, Schnoll R, Collman RG, et al. Bidirectional Associations among Nicotine and Tobacco Smoke, NeuroHIV, and Antiretroviral Therapy. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol 2020; 15(4):694-714.

- Bryant VE, Kahler CW, Devlin KN, Monti PM, Cohen RA. The effects of cigarette smoking on learning and memory performance among people living with HIV/AIDS. AIDS Care 2013; 25(10):1308-1316.

- Chang L, Lim A, Lau E, Alicata D. Chronic Tobacco-Smoking on Psychopathological Symptoms, Impulsivity and Cognitive Deficits in HIV-Infected Individuals. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol 2017; 12(3):389-401.

- Helleberg M, Afzal S, Kronborg G, Larsen CS, Pedersen G, Pedersen C, et al. Mortality attributable to smoking among HIV-1-infected individuals: a nationwide, population-based cohort study. Clin Infect Dis 2013; 56(5):727-734.

- Saylor D, Dickens AM, Sacktor N, Haughey N, Slusher B, Pletnikov M, et al. HIV-associated neurocognitive disorder--pathogenesis and prospects for treatment. Nat Rev Neurol 2016; 12(4):234-248.

Figures

Figure 1: Mean CEST signal in the CTX and HIP @ 2ppm and 3.5 ppm. [*] indicates significant differences between groups. (a) There is a significant decrease in signal on the CTX @ 2 ppm for nicotine-only mice when compared to all other groups. (b) No significant differences in signal on the HIP @ 2 ppm exist between groups. (c) There is a significant increase in signal on the CTX @ 3.5 ppm between nicotine-only mice and mice that received no nicotine. (d) No significant differences in signal on the HIP @ 3.5 ppm exist between groups.

Figure 2: Mean MRS signal of glutamate in the CTX and HIP. [**] indicates plausible differences between groups. (a) No significant differences in signal on the CTX @ 2 ppm are shown, though mice that received ARV treatment may have experienced a slight signal increase when compared to the controls. (b) No significant differences exist in signal on the HIP.

Figure 3: Mean MRS signal of myo-inositol in the CTX and HIP. [*] indicates a significant difference between groups. (a) There is a significant increase in signal on the CTX for ARV+nicotine mice when compared with controls. (b) No significant differences in signal on the HIP exist between groups.

Figure 4: Mean MRS signal of total choline in the CTX and HIP. [*] indicates a significant difference between groups. (a) There is a significant increase in signal on the CTX for nicotine-only mice when compared with controls and ARV+nicotine mice. (b) There is a significant decrease in signal on the HIP for all treatment groups when compared with controls.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.58530/2023/3171