3168

Metabolite detection in plants: A new application field for CEST?1Experimental Physics 5, University of Wuerzburg, Wuerzburg, Germany, 2Leibniz-Institute of Plant Genetics and Crop Plant Research, Gatersleben, Germany

Synopsis

Keywords: CEST & MT, Metabolism, Technology transfer

Chemical shift imaging (CSI) is rather challenging for the in vivo detection of low concentrated metabolites in plants due to its intrinsic low detection sensitivity and the need for accurate water suppression in the presence of magnetically inhomogeneous plant structures. As an alternative solution, we propose Chemical Exchange Saturation Transfer (CEST) for spectroscopic imaging. Within the work, several plant models were identified where CEST can be used as a versatile alternative for the detection of sugar and amino acids with increased spatial resolution and sensitivity, which demonstrates that CEST has a high potential for plant examinations.Introduction

Localized, multi-voxel NMR spectroscopy (Chemical Shift Imaging, CSI) allows for the in vivo detection of metabolites in living plant tissues1, but it has the major disadvantage of low detection sensitivity with the well-known limitations: Long acquisition times paired with small acquisition matrices, leading to low spatial resolutions and poor point spread functions. Furthermore, magnetic field inhomogeneities inside the plant strongly influence the quality of the NMR spectra and the water suppression efficiency. This problem is especially prominent in plant tissues with very (magnetically) heterogenous structures accompanied by very short T2* relaxation times.In medical research, Chemical Exchange Saturation Transfer (CEST)2 has attracted high interest as a tool for the detection of metabolites and proteins in the body. In this work, we transferred this approach from medical to plant science and propose it as an alternative method for the detection of sugar and amino acids in plants. We demonstrate the feasibility and the superior performance of CEST on a variety of different plant seeds and grains (like pea, barley, maize, tomato, potato), discuss the suitable choices of (CEST) sequence parameters, and show its advantages compared to CSI.

Methods

All experiments were performed at 9.4 and 11.7T. The overall aim was to detect the spatial distribution of sugar and amino acids, which have exchangeable protons around 1ppm (hydroxyl group)3 and 3ppm (amine group)4. Therefore, we performed CEST experiments in the range from +-5ppm. CEST saturation parameters were optimized for different samples: in many applications, low saturation parameters (e.g. only a single 200ms block pulse with a power of 2µT) led already to a sufficient CEST contrast. For the read-out a 2D spin echo sequence (RARE) was used. B0 correction for CEST was performed with the WASSR5 technique. For direct comparison, CSI experiments were also performed on the same slice. The spatial resolutions of the CEST experiments were in the range of 50-100µm, whereas for CSI only lower resolutions (above 300µm) in a similar time were possible. Metabolite maps were calculated by integration over the corresponding peaks in the asymmetry spectrum (CEST) or the NMR spectrum (CSI).Results

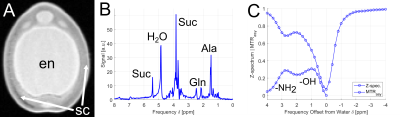

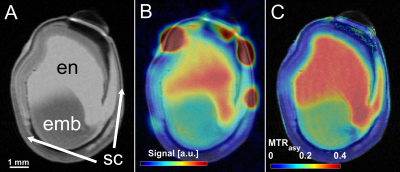

As a first demonstration example, young peas containing primary liquid endosperm surrounded by a seed coat (Fig.1A) were investigated. The endosperm contains mainly sugars and amino acids (Suc, Aln, Glu, see Fig.1B) at a mildly acidic pH value of around 5.9. Both, sugar and amino acids, could be detected by CEST showing peaks at around 1ppm and 3ppm, respectively (see Fig.1C).In addition, it was noticed that CEST exhibit a much lower sensitivity to magnetic field inhomogeneities than CSI; this is also illustrated by an experiment on a pea at middle developmental stage (Fig.2): Magnetic field inhomogeneities led to major differences in T2* within the endosperm region, making the comparison of CSI spectra within the sample rather unreliable. Correspondingly, signal gradients within the endosperm were erroneously observed in the metabolite maps (Fig.2B); in contrast, CEST delivered a constant metabolite signal within the endosperm (Fig.2C). In addition, voxels in the CSI maps could be observed in which the metabolite signals were masked by water signal. This effect can be explained by the insufficient water suppression due to B0-inhomogeneities. For CEST, the same inhomogeneities did not pose a severe problem, as they could be corrected in post-processing (WASSR, B0 correction).

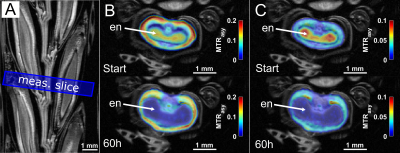

In addition, CEST experiments were conducted on several other seeds such as barley or maize, but also larger fruits like tomatoes and potatoes. The experimental data were again compared and validated by CSI and other invasive (non-NMR) techniques like mass spectroscopy. As an important example, a growing barley grain attached to an intact ear was monitored via CEST over 60h, showing a clear temporal decrease of the sugar and amino acid signal within the endosperm (Fig.3).

Discussion

Within this work CEST was successfully transferred to plant science: It was demonstrated that CEST is a versatile tool for the detection of sugar and amino acids in seeds and fruits. Several plant models and applications, like monitoring dynamic growing processes, were identified where CEST-MRI is not only feasible, but provided an added value. In contrast to NMR spectroscopy, CEST does not enable the clear differentiation between individual sugars or amino acids, but delivers much higher spatial resolutions in rather short acquisition times. Furthermore, the decreased sensitivity to magnetic field inhomogeneities, which usually occur in plant tissues, is a great advantage of CEST compared to conventional spectroscopic methods like CSI. Intrinsic B0 correction was shown to be of fundamental importance, especially for the calculation of the asymmetry spectra of sugar signals. In summary, the applicability and the advantages of CEST for spectroscopic plant MRI of exchanging spins were demonstrated. Moreover, quantitative CEST-approaches such as QUESP for the determination of exchange rates might provide additional precious information.Conclusion

In our opinion, CEST-MRI is a promising tool for the examination of plant tissues and should be pursued in future research.Acknowledgements

No acknowledgement found.References

1. Borisjuk L, Melkus G. Nuclear magnetic resonance imaging of metabolites in plants and animals. In: Hough R, Camarillo J (Eds.): In vivo imaging: new research. New York: Nova Science Publishers (2014).

2. Van Zijl PCM, Yadav NN. Chemical exchange saturation transfer (CEST): What is in a name and what isn’t? Magn Reson Med. 2011;65(4):927-948.

3. Chan KWY, McMahon MT, Kato Y, et al. Natural D -glucose as a biodegradable MRI contrast agent for detecting cancer. Magn Reson Med. 2012;68(6):1764-1773.

4. Cai K, Haris M, Singh A, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging of glutamate. Nat Med. 2012;18(2):302-306.

5. Kim M, Gillen J, Landman BA, Zhou J, Van Zijl PCM. Water saturation shift referencing (WASSR) for chemical exchange saturation transfer (CEST) experiments. Magn Reson Med. 2009;61(6):1441-1450.

Figures