3162

The impact of motion and motion correction in dynamic glucose enhanced MRI1Medical Radiation Physics, Lund University, Lund, Sweden, 2Department of R&D Advanced Applications, Olea Medical, La Ciotat, France, 3BioMedical Engineering and Imaging Institute, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, NY, United States, 4Russell H. Morgan Department of Radiology and Radiological Science, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD, United States, 5F.M. Kirby Research Center for Functional Brain Imaging, Kennedy Krieger Institute, Baltimore, MD, United States, 6Siemens Healthcare GmbH, Erlangen, Germany, 7Siemens Healthcare AB, Malmö, Sweden, 8Department of Radiology, Lund University, Lund, Sweden, 9Lund University Bioimaging Centre, Lund University, Lund, Sweden, 10Department of Medical Imaging and Physiology, Skane University Hospital, Lund, Sweden

Synopsis

Keywords: CEST & MT, Motion Correction

Dynamic glucose-enhanced (DGE) MRI is a dynamic chemical exchange saturation transfer (CEST) method that can provide information about D-glucose uptake in tissue. DGE signal changes are small and so-called pseudo-DGE effects can appear as true DGE effects. In this study, we investigated how motion and motion correction influenced the DGE effects using both a realistic (measured) motion pattern and an arbitrary motion pattern. We observed that pseudo-DGE effects are governed by the head motion pattern and originate either from tissue mixing at tissue interfaces or B0-shifts. Although motion correction can reduce these effects, new pseudo-DGE effects can also be introduced.Introduction

In recent years there have been efforts to develop natural sugar, D-glucose, as a chemical exchange saturation transfer (CEST) contrast agent. Dynamic glucose-enhanced (DGE) MRI is a dynamic CEST method where information about D-glucose delivery, uptake, and metabolism can be obtained.1-8 However, at the clinical field strength of 3 T, DGE signal changes are small and so-called pseudo-DGE effects can hamper data interpretation.9 Pseudo-DGE effects originate either from tissue mixing at tissue interfaces or B0-shifts and can mimic true DGE effects. However, it is unclear, how different motion patterns influence these effects. Applying retrospective motion correction may either remove true DGE effects or create additional pseudo-DGE effects, leading to misinterpretation. We investigated how motion and motion correction influence DGE effects using both a realistic (measured) motion pattern and an arbitrary motion pattern.Methods

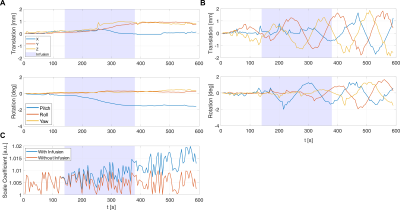

A previously developed numerical head phantom (including a brain tumor), including susceptibility modeling to estimate B0-changes and tissue-based Z-spectra, was used to simulate the effect of two motion patterns on DGE images, both with and without D-glucose infusion.10 The first motion pattern was derived from a patient using Elastix (Fig. 1A).11 This realistic motion pattern, occurring during a DGE experiment, showed a translation in the Z-direction and a pitch rotation similar to nodding, which were attributed to involuntary relaxation of the neck muscles. The second motion pattern was an arbitrary non-continuous motion (Fig. 1B). In addition, volumetric changes of the lateral ventricles (LV) were simulated to study the effects of dilatation caused by D-glucose loading and cardiac pulsations (Fig. 1C).4,12,13 The simulated DGE time series had a 5 s temporal resolution and a duration of 690 s, consisting of a baseline (0-140 s), D-glucose infusion (140-380 s), signal increase and decay (380-565 s). “Ground truths” without motion or B0-changes were simulated with and without D-glucose infusion.Retrospective motion correction included a PCA-based denoising algorithm.14 The denoised data was transformed by a custom histogram matching algorithm and motion corrected using a rigid pairwise registration scheme.

The DGE signal SDGE(t) was estimated using

$$S_{DGE}(t)=\frac{S_{base}-S_{sat}(t)}{S_{0}}$$

Sbase is the average baseline signal, Ssat(t) the saturated signal, and S0 the average non-saturated signal. Averaged area under curve (AUCmean) maps were calculated for a time interval (240-305 s) using

$$AUC_{mean}=\frac{\sum_0^tS_{DGE}(t)}{N}$$

Regions-of-interest (ROIs) were drawn for tumor tissue, white matter (WM), gray matter (GM) and CSF to extract the dynamic response curves.

Results

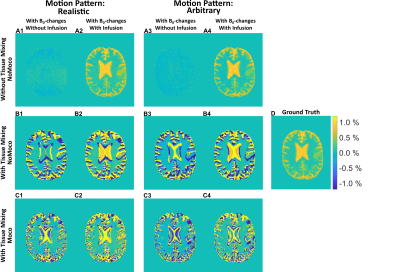

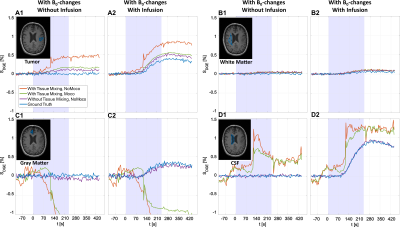

Figure 2 shows the AUCmean-maps for both head motion patterns, with/without tissue mixing, with/without infusion and with/without motion correction. Figures 2.A1-A4 reveal a spatially-gradual pseudo-DGE effect originating from small B0 shifts consequential to the rigid head movement, leading to a more positive signal increase in the center of the brain. Figures 2.B1-B4 show hypo-/and hyperintense pseudo-DGE effects caused by tissue mixing due to rigid head motion and ventricular motion, as well as dynamic B0-changes. Adding motion correction (Figs. 2.C1-C4) reduced the overall appearance of pseudo-DGE effects but also introduced new effects in regions with many tissue interfaces such as GM and the lateral ventricles.Figures 3 and 4 show extracted dynamic response curves for the ROIs before and after rigid motion correction. For the realistic pattern, the positive pseudo-DGE effect in tumor tissue was substantially reduced after motion correction (Figs. 3.A1-A2) and closer to the ground truths. WM curves showed only minor effects of motion and corrections (Figs. 3.B1-B2). Both GM and CSF curves had hypo- and hyperintense pseudo-DGE signal (Figs. 3.C1-C2, D1-D2). After motion correction, the signal was closer to ground truth but still heavily contaminated by residual pseudo-DGE effect.

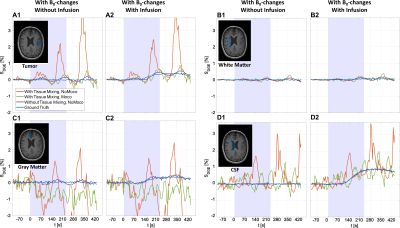

For the arbitrary motion pattern, dynamic response curves showed periodic hypo- and hyperintensities, both with and without motion correction, especially in tumor, GM and CSF (Fig. 4). The periodic hypo- and hyperintensities reflected the oscillating pattern of the arbitrary motion. In tumor, WM, and CSF, motion correction resulted in dynamic response curves that were more similar to the ground truth. However, severe artefacts were still present in GM after motion correction.

Discussion

Different motion patterns led to pseudo-DGE effects originating from B0-changes and tissue mixing caused by rigid motion. Tumor tissue, with many tissue interfaces, showed a reduction in positive pseudo-DGE effects after motion correction. However, additional pseudo-DGE contrast could occur when motion correction was applied. This was observed especially in GM and the lateral ventricles where many tissue interfaces exist. WM, which is fairly homogenous, showed mainly pseudo-DGE effects originating from B0-changes. These effects cannot be removed by motion correction.The arbitrary head motion results confirmed that the pseudo-DGE effects correspond to the motion pattern. This is similar to what has been described previously in the fMRI literature, where motion, when it is correlated with the stimulus, may mimic activated voxels.15,16 Unfortunately, the typical head motion due to neck muscle relaxation leads to a pseudo-uptake curve resembling the dynamic response uptake curve.

Conclusion

Motion and B0-changes complicate the DGE image interpretation since induced pseudo-DGE effects can be tangled with true DGE effects. These pseudo-DGE effects are governed by the head motion pattern. Although motion correction can reduce these effects, motion correction can also introduce new pseudo-DGE effects. Therefore, designing advanced retrospective motion correction may be crucial for implementation into the clinic.Acknowledgements

No acknowledgement found.References

1. Xu X, Chan KW, Knutsson L, et al. Dynamic glucose enhanced (DGE) MRI for combined imaging of blood-brain barrier break down and increased blood volume in brain cancer. Magn Reson Med. 2015;74:1556-63.

2. Xu X, Yadav NN, Knutsson L, et al. Dynamic Glucose-Enhanced (DGE) MRI: Translation to Human Scanning and First Results in Glioma Patients. Tomography. 2015;1:105-14.

3. Schuenke P, Paech D, Koehler C, et al. Fast and Quantitative T1rho-weighted Dynamic Glucose Enhanced MRI. Sci Rep. 2017 Feb;7:42093.

4. Seidemo A, Lehmann PM, Rydhög A, et al. Towards more robust glucoCEST imaging in humans at 3 T: A study of the arterial input function and the effect of infusion time. NMR in Biomed. 2021;e4624.

5. Xu X, Sehgal AA, Yadav NN, et al. d-glucose weighted chemical exchange saturation transfer (glucoCEST)-based dynamic glucose enhanced (DGE) MRI at 3T: early experience in healthy volunteers and brain tumor patients. Magn Reson Med. 2019;00:1–16.

6. Knutsson L, Seidemo A, Rydhög Scherman A, et al. Arterial Input Functions and Tissue Response Curves in Dynamic Glucose-Enhanced (DGE) Imaging: Comparison Between glucoCEST and Blood Glucose Sampling in Humans. Tomography 2018;4:2379-1381.

7. Knutsson L, Xu X, van Zijl PCM, Chan KWY. Imaging of sugar-based contrast agents using their hydroxyl proton exchange properties. NMR Biomed. 2022 Jun 4:e4784.

8. Seidemo A, Wirestam R, Helms G, et al. Tissue response curve shape analysis of dynamic glucose enhanced (DGE) and dynamic contrast enhanced (DCE) MRI in patients with brain tumor. NMR Biomed. 2022 Oct 30:e4863.

9. Zaiss M, Herz K, Deshmane A, et al. Possible artifacts in dynamic CEST MRI due to motion and field alterations. J Magn Reson. 2019;298:16-22.

10. Lehmann PM, Andersen M, Seidemo A, et al. GlucoCEST under the influence of head motion at 3 T: A numerical head phantom. In Proceedings of the 31st Annual Meeting of the ISMRM 2022. Abstract 1996.

11. Klein M, Staring K, Murphy MA, et al. elastix: a toolbox for intensity based medical image registration. IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging. 2019;29:196-205.

12. Puri B, Lewis H, Saeed N, et al. Volumetric change of the lateral ventricles in the human brain following glucose loading. Experimental Physiology. 1999;84:223-226.

13. Zhu D, Xenos M, Linninger A, et al. Dynamics of lateral ventricle and cerebrospinal fluid in normal and hydrocephalic brains. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2006;24:756-770.

14. Casagranda S, Papageorgakis C, Romdhane F, et al. Principal Component selections and filtering by spatial information criteria for multi-acquisition CEST MRI denoising. In Proceedings of the 31st Annual Meeting of the ISMRM 2022. Abstract 2080.

15. Freire L, Mangin JF. Motion correction algorithms may create spurious brain activations in the absence of subject motion. Neuroimage. 2001;14:709-722.

16. Yakupov R, Lei J, Hoffmann MB, Speck O. False fMRI activation after motion correction. Hum Brain Mapp. 2017;38:4497–4510.

Figures