3158

Adjustment of Saturation and Rotation Effects (AROSE) for CEST Imaging

Tao Jin1 and Julius Juhyun Chung1

1Radiology, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA, United States

1Radiology, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: CEST & MT, CEST & MT

Endogenous CEST signal usually has low specificity due to contamination from the magnetization transfer (MT) effect and from other labile protons with close Larmor frequencies. We propose to improve CEST signal specificity with AROSE which measures the difference between CEST signals acquired with similar average saturation power but largely different duty cycles (DC), e.g., a continuous wave or a high DC pulse train versus a low DC one. Simulation and creatine phantom studies showed that AROSE can improve the specificity of slow to intermediate exchanging CEST signals with relatively limited loss of sensitivity.Introduction

CEST MRI signal is usually contaminated by magnetization transfer (MT) from semi-solids and overlapping exchange signals from labile protons different from the molecules of interest1-4. We previously proposed an Average Saturation Efficiency Filter (ASEF) which uses two pulse trains with similar average saturation power but highly unequal duty cycles where the difference becomes an exchange rate filter suppressing MT and overlapping fast exchange signals5-6. In this work, we have expanded this filter to suppress both overlapping slow and fast exchanges by modulating the rotation transfer effect in the low-duty cycle pulse train. The signal properties of AROSE were evaluated by computer simulation and validated by phantom experiments.Methods

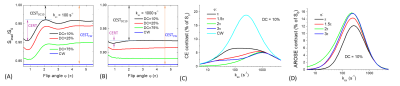

Simulations: AROSE takes the difference between CEST signals measured by a continuous wave (or high duty cycle) saturation and a low duty cycle (DCl) pulse train of a particular flip angle (Fig. 1). CEST signals were simulated by Bloch-McConnel Equations which include 3 exchanging pools of free water protons, labile protons, and bound water protons, assuming a chemical shift between the labile proton and water of 1.9 ppm, a fraction of labile proton of 0.001, the T1 (T2) of water, labile proton, and bound water protons is 2 s (66.6 ms), 2 s (66.6 ms), and 2 s (10 ms), respectively.Phantom experiments: MR experiments were performed at 9.4 T. Two sets of phantoms were prepared: 1) 12% Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) and PBS at pH 7.0 with and without 40 mM Creatine heated to 95ºC to denature the BSA 2) 30 mM Creatine in PBS titrated to pH = 6.0, 6.3, 6.7, 7.0, 7.3, 7.6, and 7.9. The saturation preparation schemes, with a duration of 6-s, consisted of either a single CW block pulse or a DCl =10% pulse train with varied flip angles (φ): π,1.5 π, or 2π. The B1 for the first set of phantoms was 0.7 μT for CW and an average B1 = 0.75 μT for the DCl pulse train and either 0.47 or 0.94 μT for both schemes in the second set of phantoms. Images were acquired by single-slice spin-echo EPI at room temperature.

Results

Fig. 1A-B shows simulated CEST contrast for CW and pulse trains with varying DC across different φ at two different exchange rates. At kex = 100 s-1, there is a considerable disparity between the contrasts of CW versus the pulse train which increases as DC becomes low. Furthermore, this disparity is maximized at φ of 2π and >4π while this difference is smaller at φ<2π due to the rotation transfer effect. At kex = 1000 s-1, the disparity between the two pulse trains is only slightly affected by φ because the rotation transfer effect is small. Fig. 1C shows these CEST contrasts across different exchange rates at CW and pulse trains with DCl=10% and φ of π, 1.5π, 2π, and 3π with the resultant exchange rate filtering of AROSE being demonstrated in Fig. 1D. The CEST contrast of the DCl pulse train is like that of CW at fast exchange rates, but is much smaller at slower exchange rates for 2π, closer at 1.5π/3π, yet closest with π. As a result, the sensitivity of their difference, i.e., the AROSE signal, is only slightly lower than CW for exchange rates of 150 to 500 s-1, suppressed at kex > 3000 s-1, while at kex < 30 s-1 it is modulated by φ. For creatine in heated-denatured BSA, the Z-spectra of the pH = 7.0 phantom show larger differences in the 1.9 ppm dips for CW than DCl pulse train saturation (Fig.2A). The spectra match well for offsets > 3.5 ppm indicating the MT effect can be effectively minimized by AROSE. In Fig. 2B, AROSE2π is only slightly lower than that of CW at lower pH values but much smaller at higher pH while AROSEπ is suppressed at both low and high pH. At a higher power (Fig. 2C), the peaks of signals shift to higher pH phantoms with fast exchange rates. AROSE2π is much closer to MTRasym for most phantoms, while AROSEπ shows a difference across all pH. AROSE1.5π shows a contrast that is between the AROSE2π and AROSEπ. The signal maps show the differences in contrasts for both powers in Fig. 2D.Discussion

While the filtering of MT and fast exchange has been studied in a few approaches to improve the CEST signal specificity2,4-5, there may still be contamination from non-specific and slower exchanges such as aromatic NOE or slow amides signals7. AROSE is an adjustable exchange rate filter and can improve the CEST signal specificity for slow to intermediate exchanges (e.g., 30 s-1<kex<3000 s-1) with a limited reduction in sensitivity. It can be acquired at as few as only one frequency offset, i.e., the Larmor frequency of the labile proton of interest.Conclusion

AROSE is a simple method that can minimize the MT effect and provide band-filtering of fast and slow exchange rates for CEST MRI with a relatively limited reduction in sensitivity. It can be a highly useful tool for CEST study in the slow to intermediate exchange regime.Acknowledgements

This work is supported by NIH grant NS100703.References

1. Zaiss M, Schmitt B, and Bachert P. Quantitative separation of CEST effect from magnetization transfer and spillover effects by Lorentzian-line-fit analysis of z-spectra. J Magn Reson 2011;211(2):149-55.2. Zu Z, Janve V, Xu J, et al. A new method for detecting exchanging amide protons using chemical exchange rotation transfer. Magn Reson Med 2013;69(3):637-647.

3. Xu X, Yadav N, Zeng H, et al. Magnetization transfer contrast-suppressed imaging of amide proton transfer and relayed nuclear overhauser enhancement chemical exchange saturation transfer effects in the human brain at 7T. Magn Reson Med 2016;75(1):88-96.

4. Chen L, Barker P, Weiss R, et al. Creatine and phosphocreatine mapping of mouse skeletal muscle by a polynomial and Lorentzian line-shape fitting CEST method. Magn Reson Med 2019;81(1):69-78.

5. Jin T and Chung J. Average saturation efficiency filter (ASEF) for CEST imaging. Magn Reson Med 2022; 88(1):254-265.

6. Chung J and Jin T. Average saturation efficiency filter ASEF-CEST MRI of stroke rodents. Magn Reson Med 2022; Online ahead of print.

7. Jin T, Kim SG. In vivo saturation transfer imaging of nuclear overhauser effect from aromatic and aliphatic protons: implication to APT quantification. Proceedings of International Society for Magnetic Resonance in Medicine; 2013; Salt Lake City, Utah, USA. p 2528. (Proceedings of International Society for Magnetic Resonance in Medicine).

DOI: https://doi.org/10.58530/2023/3158