3154

Is Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor Antagonism after Ischemia Effective in Alleviating Hepatic Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury in Rats?1Asan Medical Center, Seoul, Korea, Republic of, 2Gangneung Asan Hospital, Gangneung, Korea, Republic of

Synopsis

Keywords: Liver, Ischemia, reperfusion, aryl hydrocarbon receptor, L-kynurenine

Recent studies suggest that aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) act as an important mediator of ischemic injury in brain. In particular, pharmacological inhibition of AhR activation after ischemia has been shown to attenuate cerebral ischemia-reperfusion (IR) injury. In this study, we investigated whether AhR antagonist administration after ischemia was also effective in ameliorating hepatic IR injury. Our results indicate that treatment with the AhR antagonist after ischemia alleviate liver damage, as evidenced by serum ALT and AST levels, MRI-based liver function indices, and histologic and molecular analysis. Thus, adequate AhR antagonist activity is a potential therapeutic approach for hepatic IR injury.INTRODUCTION

Recent studies have suggested that cerebral ischemia induces AhR activation and exacerbates neuronal damage.1,2 This is because L-kynurenine (L-Kyn), an endogenous ligand of AhR, is accumulated in the brain during ischemia and triggers the activation of AhR.1 Observations in the brain raise the possibility that similar pathways can be involved in the liver. Because L-Kyn is produced in a significant amount in the liver through the degradation of L-tryptophan by tryptophan-2,3-dioxygenase (TDO),3 it is more likely to accumulate in the liver than in the brain due to ischemia. This means that ischemia-induced AhR activation and tissue damage after reperfusion could be greater in the liver than in the brain. Therefore, the inhibition of AhR activation after ischemia is considered to be effective in suppressing hepatic IR injury. However, to the best of our knowledge, the effects of AhR antagonism on hepatic IR injury have not yet been reported. In the present study, we investigated the protective effects of AhR antagonism after ischemia in a rat hepatic IR injury model.MATERIALS & METHODS

Animal model: A 70% partial hepatic IR (45-minute ischemia and 24-hour reperfusion) injury was induced in rats (Fig.1).4,5 We administered 6,2',4'-trimethoxyflavone (TMF, 5 mg/kg) intraperitoneally 10 minutes after ischemia. Twenty-four male rats were randomly divided into three groups: (1) a sham group with no IR modeling or vehicle injection (n = 8); (2) a control group with IR modelling and vehicle injection (n = 8); and (3) a TMF group with IR modeling and administration of the drug at 10 minutes after ischemia (n = 8). Blood samples were obtained at 3 and 24 hours after reperfusion. Rats were sacrificed 24 hours after reperfusion and hepatic IR injury was observed using liver samples.MRI analysis: MRI data were obtained at 3 and 24 hours after reperfusion. The MRI protocols included T1-WI and T1 mapping. MRI images were acquired before and 20 minutes after administration of Gd-EOB-DTPA (25 mM/kg). The mean SI values and T1 relaxation time were measured on T1-WIs and T1 maps obtained before and 20 minutes after Gd-EOB-DTPA administration. Two Region of interests (ROIs) were randomly placed in the liver and paravertebral muscles in the MRI images. MRI-based liver function indices were calculated from the SI measurements or T1 relaxation time before (SI-pre, T1-pre) and 20 minutes after (SI-post, T1-post) Gd-EOB-DTPA administration as follows: (1) relative enhancement (RE) of the liver = (SI-post – SI-pre)/SI-pre; (2) LMR = SI-post of the liver/SI-post of the muscle; (3) T1-post = T1-post values of the liver; and (4) ∆T1 = T1-pre – T1-post.

Histological and molecular analysis: H&E staining, TUNEL assay, western blot, immunohistochemical staining, qRT-PCR, and LC-MS/MS were performed to analyze changes in tissue damage caused by hepatic IR.

Statistical analysis: Data in multiple groups were compared using a one-way analysis of variance with Tukey’s post-hoc test. All the data are expressed as means ± standard deviations. Values of P < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

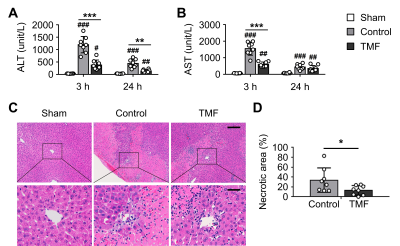

MRI-based liver function indices: The RE values at 3 and 24 hours after reperfusion were significantly lower in the TMF group than in the control group (Fig.1). The ∆T1 values at 24 hours after reperfusion were significantly lower in the TMF group than in the control group.Changes in serum ALT and AST levels: The serum ALT levels were significantly lower in the TMF group than in the control group at 3 and 24 hours after reperfusion (Fig 2). The serum AST levels were significantly lower in the TMF group than in the control group at 3 hours after reperfusion.

Reduction of necrotic area by TMF treatment: Extensive hepatocellular necrosis was observed in the control and TMF groups at 24 hours after reperfusion (Fig 2). The necrotic area percentage in the TMF group was significantly lower than that in the control group.

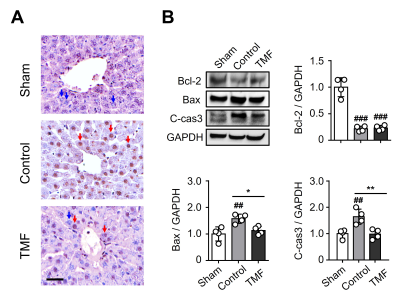

Alleviation of apoptosis with TMF treatment: TUNEL-positive cells (round brown nuclei) were mainly observed in the control and TMF groups but rarely in the sham group (Fig. 3). The expression of Bax and C-cas3 proteins in the TMF group was significantly lower than in the control group.

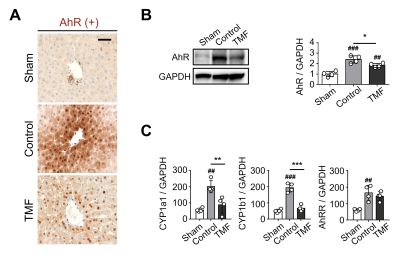

Suppression of AhR expression by TMF administration: The TMF group showed a significant decrease in AhR proteins than did the control group (Fig. 4). In addition, as a result of analyzing the expression change of the AhR target genes, the expression of CYP1a1 an CYP1b1 in the TMF group was significantly lower than in the control group.

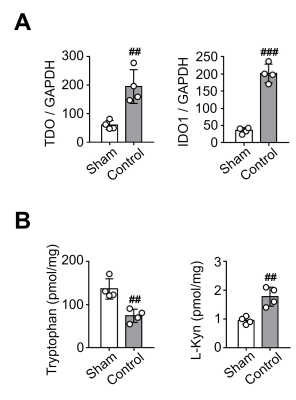

Changes in tryptophan metabolism due to hepatic I/R injury: The levels of TDO and indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase 1 (IDO1) mRNA expression in the control group were significantly higher than in the sham group (Fig. 5). Tryptophan levels were significantly lower in the control group than in the sham group, and L-Kyn levels were significantly higher in the control group than in the sham group.

CONCLUSION

Our findings demonstrated that post-ischemia administration of AhR antagonists has hepatoprotective effects that ameliorate hepatic IR injury. We propose that adequate AhR antagonist activity is a potential therapeutic approach for hepatic I/R injury. Nevertheless, further studies are needed to elucidate the mechanisms underlying the hepatoprotective effect to assess potential clinical applications of AhR antagonist administration.Acknowledgements

This study was supported by a grant (2019IL0602) from the Asan Institute for Life Sciences, Asan Medical Center, Seoul, Republic of Korea and the Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF-2018R1C1B6003879).References

1. Cuartero, M. I. et al. L-kynurenine/aryl hydrocarbon receptor pathway mediates brain damage after experimental stroke. Circulation 130, 2040-2051, doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.011394 (2014).

2. Padmanabhan, A. & Haldar, S. M. Neuroprotection in ischemic stroke: AhR we making progress? Circulation 130, 2002-2004, doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.013533 (2014).

3. Green, A. R., Woods, H. F. & Joseph, M. H. Tryptophan metabolism in the isolated perfused liver of the rat: effects of tryptophan concentration, hydrocortisone and allopurinol on tryptophan pyrrolase activity and kynurenine formation. Br J Pharmacol 57, 103-114, doi:10.1111/j.1476-5381.1976.tb07660.x (1976).

4. Zabala, V. et al. Transcriptional changes during hepatic ischemia-reperfusion in the rat. PLoS One 14, e0227038, doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0227038 (2019).

5.Karatzas, T., Neri, A. A., Baibaki, M. E. & Dontas, I. A. Rodent models of hepatic ischemia-reperfusion injury: time and percentage-related pathophysiological mechanisms. J Surg Res 191, 399-412, doi:10.1016/j.jss.2014.06.024 (2014).

Figures