3139

Change in ATP flux after propionate ingestion in healthy volunteers Using 31P MRS Saturation Transfer.1University of Nottingham, Nottingham, United Kingdom, 2NIHR Nottingham Biomedical Research Centre, Nottingham University hospitals NHS trust, Nottingham, United Kingdom, 3Scottish Universities Environmental Research Centre (SUERC), University of Glasgow, Glasgow, United Kingdom, 4Nottingham Biomedical Research Centre NUH, University of Nottingham, Nottingham, United Kingdom, 5Section for Nutrition, Faculty of Medicine, Imperial College London, London, United Kingdom

Synopsis

Keywords: Liver, Spectroscopy, Multinuclear

Propionate is a short chain fatty-acid absorbed in the colon and metabolised in the liver with some evidence showing that consumption can increase energy homeostasis. Three healthy participants have been studied to date with 31P saturation transfer experiments performed pre and 180 minutes post consumption of an inorganic-propionate ester using 1D-slice-selective-ISIS. The exchange rate constant (k) was calculated to be higher than previous studies despite similar methodologies. Whilst at this time no conclusions can be drawn about the effect of consuming Inorganic Propionate Ester thus far, this study shows the applicability of using 31P saturation transfer in simpler intervention studies.

Introduction

Propionate is a short chain fatty-acid produced by the fermentation of carbohydrates in the colon. Little is known about the pathways by which propionate is metabolised, but there is some evidence that enriching colonic propionate has positive effects on energy homeostasis and glycaemic control (1,2). Propionate absorbed from the colon is efficiently metabolised in the liver, with very little detectable in peripheral blood. However, the methods by which propionate is metabolised by the human liver is poorly understood. The aim of this study is to investigate the effect of propionate consumption on liver ATP flux rates using 31P MRS saturation transfer.Methods

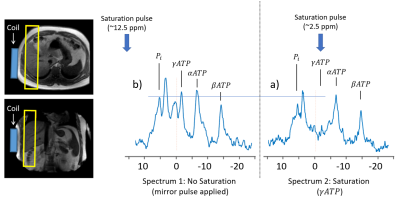

Healthy Participants (Aged 24 – 38 yrs, BMI 20-25 kg/m2, no metabolic disorders) were recruited and informed consent obtained. On the day of the study, participants arrive having fasted from 10 pm the previous night and underwent two MRI 31P saturation transfer experiments, before (baseline) and 180 minutes after consuming 10g of an Inulin Propionate Ester (IPE) dissolved in 100ml of water to allow for transport to the colon (3).All scans were performed on a Philips Achieva 3T (Philips Medical Systems, Best, the Netherlands) using a 31P transmit–receive 14-cm diameter loop coil (Flex coil P-140) placed over the bulk of the liver confirmed by 1H scout images. Spectra were obtained using 1D ISIS slice selective sequence (excitation block pulse angle = 900, slice thickness = 30 mm). Initially, a scout spectrum was acquired to determine the frequency of the saturation pulses used in the ATP flux experiment. Subsequently, two spectra were acquired – one with saturation of the γ-ATP peak (~-1.5ppm) and one with saturation targeted equidistant on the opposite side of the Pi peak (to cancel out unwanted direct saturation effects (4,5)). Each spectra took ~20 minutes to acquire during free breathing (TR = 1600 ms, number of averages = 200)

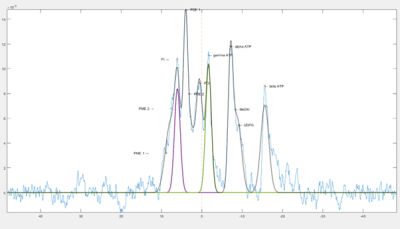

Analysis was performed using an in-house MATLAB (2022b, Mathworks) script. Spectra were phase corrected and baseline fitted before gaussian fits were applied to each metabolite (Figure 1).

Inorganic phosphate concentrations were estimated by referencing peak area in the unsaturated (mirror) spectra to the peak and assuming literature ATP values (2.5 mmol/l (5)).

The peak areas for γ-ATP and Pi were used to calculate k, the exchange rate constant from Eq 1:

$$ k = \frac{M_{Pi}^{0}-M_{Pi}^{\infty}}{M_{Pi}^{\infty }T1_{Pi}^{int''}} $$ [1]

where $$${M_{Pi}^{\infty }}$$$ is the signal when γ-ATP is saturated, $$${M_{Pi}^{0 }}$$$ is the signal when saturation is mirrored, and T1int is assumed to be 0.73 s for the liver (5).

For initial comparisons, intra-observer variability was estimated by reanalysing the data 3 times and determining the standard deviation on values for each subject.

Results

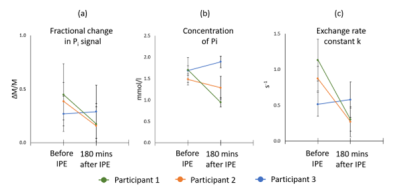

To date, three participants have been recruited and completed the study (2 male, 1 female). 31P spectra had good SNR with well resolved phosphate metabolite peaks (figure 2).Mean fractional changes in Pi signal before and after IPE consumption were 0.37 and 0.21 respectively and mean inorganic concentrations before and after IPE consumption were 1.62 ± 0.12 mmol/l and 1.37 ± 0.48 mmol/l respectively (figure 3a and b)

During the saturation experiment, the peak was well saturated, and the subsequent saturation of inorganic phosphate could be easily measured. The average k values before and after IPE consumption were 0.84 ± 0.31 s-1 and 0.38 ± 0.17 s-1 respectively (figure 3c).

Discussion

31P MRS provides a powerful method of determining ATP concentrations and dynamics in vivo. The saturation transfer experiment allows a unique insight into the mechanistic effects underlying normal human physiology as well as metabolic disorders and disease. This study has shown the feasibility of applying this methodology in a simple intervention study. The concentration values of hepatic phosphates are thus far similar to previous studies (3,4). However, k values were higher than in previous work ((5) mean k = 0.3). This is due to a larger reduction in Pi signal during saturation and may imply that signals are being over saturated in this study – although the mirror saturation should account for these effects. Further work is needed to explore the source of this discrepancy. Whilst it is too early to determine any effects of the intervention, propionate shows promise of being a beneficial interventional substrate for metabolic disease and completion of this study will help to elucidate potential pathways of action.Acknowledgements

Thank you to the Nottingham NIHR BRC for funding this project.References

1. Tirosh A, Calay ES, Tuncman G, Claiborn KC, Inouye KE, Eguchi K, et al. The short-chain fatty acid propionate increases glucagon and FABP4 production, impairing insulin action in mice and humans. Sci Transl Med [Internet]. 2019 Apr 24 [cited 2022 Jul 25];11(489). Available from: https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/scitranslmed.aav01202. Weitkunat K, Schumann S, Nickel D, Kappo KA, Petzke KJ, Kipp AP, et al. Importance of propionate for the repression of hepatic lipogenesis and improvement of insulin sensitivity in high-fat diet-induced obesity. Mol Nutr Food Res [Internet]. 2016 Dec 1 [cited 2022 Jul 25];60(12):2611–21. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/mnfr.201600305

3. Polyviou T, MacDougall K, Chambers ES, Viardot A, Psichas A, Jawaid S, et al. Randomised clinical study: inulin short-chain fatty acid esters for targeted delivery of short-chain fatty acids to the human colon. Aliment Pharmacol Ther [Internet]. 2016 Oct 1 [cited 2022 Nov 8];44(7):662–72. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/apt.13749

4. Chen C, Stephenson MC, Peters A, Morris PG, Francis ST, Gowland PA. 31P magnetization transfer magnetic resonance spectroscopy: Assessing the activation induced change in cerebral ATP metabolic rates at3 T. Magn Reson Med. 2018;79(1):22–30.

5. Schmid AI, Chmelík M, Szendroedi J, Krššák M, Brehm A, Moser E, et al. Quantitative ATP synthesis in human liver measured by localized 31P spectroscopy using the magnetization transfer experiment. NMR Biomed [Internet]. 2008 Jun [cited 2022 Nov 7];21(5):437–43. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17910026/

Figures

Figure 1. Indicating the location of the coil and FOV. (a) spectra indicating the position and effect of the saturation and (b) mirrored saturation pulse to correct the leakage from the saturation pulse.

Figure 2. Example of the fits overlayed on spectra after baseline is corrected.

Figure 3. Change in fractional Pi signal, Pi concentration and k before and after consumption of IPE.