3117

Deformable Groupwise Registration Using a Locally Low-Rank Dissimilarity for Myocardial Strain Estimation from Cine MRI Images1The Institute of Medical Imaging Technology, School of Biomedical Engineering, Shanghai Jiao Tong University (SJTU), Shanghai, China

Synopsis

Keywords: Data Analysis, Data Processing, registration

We propose a deformable groupwise registration method using a locally low-rank (LLR) dissimilarity to estimate myocardial strain from cine MRI images. The proposed method eliminates the drift effect commonly observed in the optical flow and sequentially pairwise registration, facilitating more accurate strain estimation in the diastolic phase. Compared to the globally low-rank dissimilarity, LLR dissimilarity shows slightly better tracking accuracy by imposing the low-rank property in local image regions rather than the whole image. Experiments on a large public cine MRI dataset demonstrates the accuracy of the proposed method on tracking and strain estimation.

Introduction

Myocardial strain is a sensitive indicator of regional and global left ventricular (LV) function1.Cine-based feature tracking (FT) represents a group of methods that retrospectively estimate strains from routinely preformed cine MRI images. Existing FT methods are mainly based on optical flow or sequentially pairwise registration2,3. The optical flow is efficient, yet its performance highly depends on conceivable features, which are scarce in the myocardial region of a cine image. The pairwise registration is more robust by exploiting contextual information, yet it still suffers from a drift effect caused by accumulation of small tracking errors over the cardiac cycle.In this work, we propose a deformable groupwise registration method to estimate strain from cine MRI images. A new dissimilarity metric inspired by the locally low-rank property among aligned images is proposed to improve the adaptability of the method to local signal variances4. The proposed method is compared with alternative methods on a large public cine MRI dataset5.

Methods

Groupwise RegistrationDenoting the cine images by $$$\mathrm{f}(\mathbf{x}, \mathrm{t})$$$, and the displacement field by $$$\mathbf{d}(\mathbf{x}, \mathrm{t})$$$, the deformed cine images can be expressed as

$$\hat{\mathrm{f}}(\mathbf{x}, \mathrm{t})=\mathrm{f}(\mathbf{x}+\mathbf{d}(\mathbf{x}, \mathrm{t}), \mathrm{t}),\,\,\,\,(1)$$where $$$\mathbf{d}(\mathbf{x}, \mathrm{t})$$$ is parameterized by a control point mesh $$$\boldsymbol{\phi}(\mathrm{i}, \mathrm{j}, \mathrm{t})$$$ using cubic B-splines6. Reformulating $$$\hat{\mathrm{f}}(\mathbf{x}, \mathrm{t})$$$ into a Casorati matrix $$$\mathbf{F}$$$, its nuclear norm can be adopted as a dissimilarity metric to enforce the Globally Low-Rank (GLR) property in the aligned images7. That is,$$\mathrm{D}_{\mathrm{GLR}}=\|\mathbf{F}\|_{*}.\,\,\,\,(2)$$However, cine images often contain transient signals such as those from flow artifacts, which disobey the GLR property even after alignment. Inspired by image reconstruction methods based on Locally Low-Rank (LLR) 8, we propose a new LLR-based dissimilarity metric, defined by$$\mathrm{D}_{\mathrm{LLR}}=\sum_{\mathrm{m}}\left\|\mathbf{B}_{\mathrm{m}}\right\|_{*},\,\,\,\,(3)$$where $$$\mathbf{B}_{\mathrm{m}}$$$ represents a local Casorati matrix around the $$$\mathrm{m} $$$th voxel. The cost function is formulated by$$\min _{\boldsymbol{\phi}} \mathrm{D}_{\text {LLR }}+\lambda \mathrm{R}_{\text {spatial }}+\mu \mathrm{R}_{\text {temporal}},\,\,\,\,(4)$$where $$$\mathrm{R}_{\text {spatial }}$$$ is the spatial regularization of the control point mesh $$$\boldsymbol{\phi}$$$ based on its bending energy6, and $$$\mathrm{R}_{\text {temporal }}$$$ is the temporal regularization of $$$\boldsymbol{\phi}$$$ based on the second-order difference. $$$\lambda$$$ and $$$\mu$$$ are the regularization coefficients. Since a retrospectively-gated cine movie is cyclic, $$$\mathrm{R}_{\text {temporal }}$$$ uses the cyclic finite difference9. All images are registered to an average reference by constraining the temporal sum of $$$\boldsymbol{\phi}(\mathrm{i}, \mathrm{j}, \mathrm{t})$$$ to zero. The minimization problem is solved by the gradient projection algorithm in a multiresolution framework10.

Experiments

The groupwise-LLR registration was compared to the Farneback optical flow11, pairwise registration used by a commercial software (Segment medviso)12,13, and the groupwise-GLR registration. The Lagrange strain14 was evaluated for every method. Evaluation was performed on the Automated Cardiac Diagnosis Challenge (ACDC) dataset5 consisting of annotated short-axis cine images from 100 subjects evenly divided into five groups: without cardiac disease (NOR), hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM), abnormal right ventricle (ARV), myocardial infarction (MINF), and dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM). Statistical comparison was performed with two-sample t-test.

Results

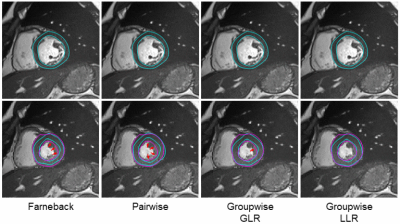

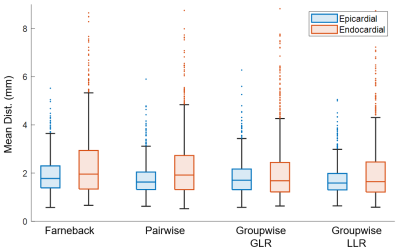

Figure 1 shows the tracking results of the four studied methods in a subject. Both groupwise registration methods tracked the endocardial contour more accurately than the other two methods. Furthermore, groupwise-LLR registration slightly outperformed the groupwise-GLR registration on tracking of the lateral wall.Figure 2 shows the quantitative comparison of tracking quality, measured by mean contour distance. For epicardial contours, the groupwise-LLR registration achieved a lower mean distance (1.71±0.62mm) than the optical flow (1.90±0.72mm, p<0.01), pairwise registration (1.77±0.67mm, p=0.021) and groupwise-GLR registration (1.82±0.71mm, p<0.01). For endocardial contours, the groupwise-LLR registration achieved a lower mean distance (2.04±1.28mm) than the optical flow (2.37±1.46mm, p<0.01) and pairwise registration (2.22±1.32mm, p<0.01), and a similar mean distance with the groupwise-GLR registration (2.07±1.35mm, p=0.297).

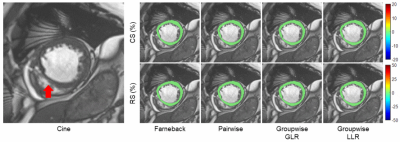

Figure 3 shows the strain maps of a MINF subject. The infarcted myocardium, located in the septum, is reflected by a lower radial strain in all registration methods. However, the delineation of the low-strain area seems to be more accurate with the two groupwise registration methods.

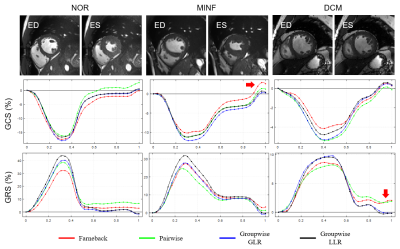

Figure 4 shows the global strain curves of three subjects from different medical groups. All methods successfully captured the reduction of strain in MINF or DCM. However, notice that the groupwise methods often achieved more accurate strains in the ending frame due to the reduction of accumulative errors.

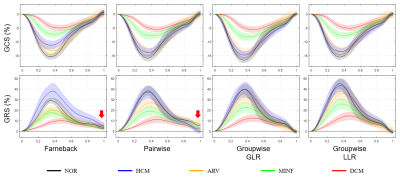

Figure 5 shows the mean and 95% confidence interval of the global strain curves for the five medical groups. Optical flow generated a higher radial strain in HCM subjects than the normal subjects, whereas the other three methods generated more similar strains, consistent with the results from a previous work15. The reduction of accumulative errors by the groupwise methods is evident (arrows). Moreover, the five medical groups seem to be more distinguishable using the groupwise-LLR measured radial strain than the other methods.

Discussion and Conclusions

The groupwise registration methods eliminate the drift effect commonly observed in the optical flow and pairwise registration methods, leading to more accurate strain estimates in the diastolic phase. LLR slightly outperforms GLR in tracking accuracy, which may translate to more accurate strain estimates. Although only analysis of short-axis cine images is shown, the proposed method can also be applied to long-axis cine images to estimate the longitudinal strain.Acknowledgements

No acknowledgement found.References

1. Smiseth OA, Torp H, Opdahl A, Haugaa KH, Urheim S. Myocardial strain imaging: how useful is it in clinical decision making? Eur Heart J 2016; 37:1196–1207.

2. Tobon-Gomez C, De Craene M, McLeod K, et al. Benchmarking framework for myocardial tracking and deformation algorithms: An open access database. Medical Image Analysis 2013; 17:632–648.

3. Barreiro-Pérez M, Curione D, Symons R, Claus P, Voigt J-U, Bogaert J. Left ventricular global myocardial strain assessment comparing the reproducibility of four commercially available CMR-feature tracking algorithms. Eur Radiol 2018; 28:5137–5147.

4. Zhang T, Pauly JM, Levesque IR. Accelerating parameter mapping with a locally low rank constraint. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine 2015; 73:655–661.

5. Bernard O, Lalande A, Zotti C, et al. Deep Learning Techniques for Automatic MRI Cardiac Multi-Structures Segmentation and Diagnosis: Is the Problem Solved? IEEE Trans Med Imaging 2018; 37:2514–2525.

6. Rueckert D, Sonoda LI, Hayes C, Hill DL, Leach MO, Hawkes DJ. Nonrigid registration using free-form deformations: application to breast MR images. IEEE transactions on medical imaging 1999; 18:712–721.

7. Peng Y, Ganesh A, Wright J, Xu W, Ma Y. RASL: Robust Alignment by Sparse and Low-Rank Decomposition for Linearly Correlated Images. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence 2012; 34:2233–2246.

8. Zhang T, Pauly JM, Levesque IR. Accelerating parameter mapping with a locally low rank constraint: Locally Low Rank Parameter Mapping. Magn Reson Med 2015; 73:655–661.

9. Royuela-del-Val J, Cordero-Grande L, Simmross-Wattenberg F, Martín-Fernández M, Alberola-López C. Nonrigid groupwise registration for motion estimation and compensation in compressed sensing reconstruction of breath-hold cardiac cine MRI. Magn Reson Med 2016; 75:1525–1536.

10. Bhatia KK, Hajnal JV, Puri BK, Edwards AD, Rueckert D. Consistent groupwise non-rigid registration for atlas construction. 2004 2nd IEEE International Symposium on Biomedical Imaging: Nano to Macro (IEEE Cat No. 04EX821), 2004; 908–911

11. Farnebäck G. Two-Frame Motion Estimation Based on Polynomial Expansion. Image Analysis 2003; 2749:363–370.

12. Morais P, Heyde B, Barbosa D, Queirós S, Claus P, D’hooge J. Cardiac Motion and Deformation Estimation from Tagged MRI Sequences Using a Temporal Coherent Image Registration Framework. 2013; 7945:324.

13. Morais P, Marchi A, Bogaert JA, et al. Cardiovascular magnetic resonance myocardial feature tracking using a non-rigid, elastic image registration algorithm: assessment of variability in a real-life clinical setting. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson 2017; 19:24.

14. Lai WM, Rubin D, Krempl E. Introduction to Continuum Mechanics. 2010

15. Frontiers | DeepStrain: A Deep Learning Workflow for the Automated Characterization of CardiacMechanics.https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcvm.2021.730316/full (Accessed: Sep. 24, 2022)

Figures

Figure 1. Tracking results of the epicardial and endocardial contours. Contours were manually drawn in the end-diastolic frame and then automatically tracked by the algorithms. The first row shows displacement of the contours over the cardiac cycle. The second row shows the predicted contours (cyan) and the manually-drawn contours (magenta) at end-systole. Arrows point to the inaccurate tracking by the first three methods.

Figure 2. Box-plots of the mean distances between the predicted contours and the manually-drawn contours at end-systole. The outliers only accounted for 0.7% of total data. Groupwise-LLR showed significant reduction of mean distance compared with all the other methods for the epicardial contour and with Farneback optical flow and pairwise registration for the endocardial contour.

Figure 3. Cine images of a MINF subject with corresponding circumferential and radial strain maps. The infarct is roughly located in the septum (red arrow). Groupwise registration demonstrated a smoother circumferential strain and a more accurate delineation of the infarcted myocardium in the radial strain map. (CS: circumferential strain; RS: radial strain; MINF: myocardial infarction)

Figure 4. Global circumferential and radial strain curves. The curves were plotted as a function of normalized time. The end-diastolic and end-systolic frames are shown above the strain curves of each subject. The strain at the last frame should be nearly zero since retrospectively gated cine was performed. It is thus evident that the Farneback optical flow and pairwise registration methods caused a biased diastolic strain due to error accumulation. (ED: end-diastole; ES: end-systole; GCS: global circumferential strain; GRS: global radial strain)

Figure 5. The mean and confidence interval of the global circumferential and radial strain curves over each medical group. Each curve represents an average global strain of a specific medical group. The shade around each curve represents the 95% confidence interval. The arrows highlight the drift effect of the Farneback optical flow and pairwise registration. (GCS: global circumferential strain; GRS: global radial strain; NOR: normal subjects; HCM: hypertrophic cardiomyopathy; ARV: abnormal right ventricle; MINF: myocardial infarction; DCM: dilated cardiomyopathy)