3089

Two-Stage Kalman Filtering as a Framework for Accelerated Cardiac MRI1Electrical and Computer Engineering, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada, 2Translational Biology & Engineering Program, Ted Rogers Centre for Heart Research, Toronto, ON, Canada, 3Institute of Biomedical Engineering, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada

Synopsis

Keywords: Image Reconstruction, Heart

Robust, real-time dynamic cardiac MRI (CMR) would provide information on the temporal signatures of disease that we currently cannot assess. We present a novel Kalman filtering framework that uses a priori statistics derived from a single cardiac cycle to adaptively predict temporal cardiac dynamics. Kalman filtering is ideal, as it ameliorates noise introduced from our maximum acceleration factor of 60, guarantees reconstruction fidelity, and enables flexible undersampling. Furthermore, reconstruction may be performed at an even higher temporal resolution than the training data. As such, our algorithm can be a foundation for true real-time dynamic CMR.Introduction

Cardiac MRI (CMR) is an important clinical tool for assessing cardiac 3D anatomy, mechanics, and tissue microstructure and function. However, robust, real-time dynamic CMR has yet to see clinical implementation. Despite remarkable advances such as compressed sensing (CS) and artificial intelligence (AI) 1, they have significant limitations: CS imposes constraints on the undersampling pattern, AI cannot guarantee reconstruction fidelity, and both techniques can mask important local information. These limitations are exacerbated by the potential irregularity of cardiac dynamics, which conventional CINE accounts for via data rejection and re-binning.We present a novel framework inspired by Kalman filtering and k-t accelerated imaging capable of an acceleration factor of at least 60. Our algorithm can adaptively predict temporal cardiac dynamics in the presence of a variable sinus rhythm, is amenable to multiple undersampling patterns, and does not require re-binning. This is accomplished via a statistical mathematical model derived from a training set consisting of a single cardiac cycle. Furthermore, the Kalman filter’s ability to guarantee reconstruction fidelity in the form of a minimum mean squared error (MSE) 2 naturally compensates for increased noise power resulting from high acquisition speeds. As such, our framework has broad implications by virtue of its real-time adaptation to unpredictable cardiac dynamics.

Theory

We propose the following model for dynamic cardiac MRI:$$x_{t}=f(x_{t-1})+w_{t-1}$$

$$z_{t}=Hx_{t}+v_{t-1}$$

where $$$x_{t}$$$ is the fully sampled image, $$$f(x_{t-1})$$$ is a non-linear transformation of the previous image, $$$z_{t}$$$ is k-space that has not undergone re-binning, $$$H$$$ is a sampling/regridding mask plus the Fourier transform, and $$$w_{t-1}$$$ plus $$$v_{t}$$$ are noise. In previous work 3,4 $$$f(x_{t-1})=x_{t-1}$$$. This assumes marginal changes between subsequent phases, which is not reflective of irregular cardiac dynamics. We will refer to previous work as random-walk Kalman filtering.

We propose a novel method to estimate $$$f(x_{t-1})$$$ that uses a priori temporal statistics derived from a training scan consisting of a single cardiac cycle. A statistical approach enables us to model any arbitrary phase transition, provided the current and previous cardiac phases are known. However, our method is limited by the temporal resolution of the training scan. To overcome this, consider the following example: suppose our training scan can model a phase transition from phase 1-6. We will assume that phases 2-5 lie linearly in between 1 and 6. This assumption allows us to estimate $$$f(x_{t-1})$$$, which has significant implications on the acceleration factor.

Methods

Simulations were performed in MATLAB R2020a or later using DICOM’s from previously acquired fully sampled CINE datasets. Training data and test data were both obtained from the same patient. All simulations (except for the fourth) were repeated for cartesian, golden-angle radial, and spiral undersampling patterns. MSE convergence was verified for all simulations.The first scenario examined our algorithm’s ability to reconstruct multiple periodic cardiac cycles. The second scenario simulates an arrhythmic event via an early return to systole. The third scenario simulates an increase in the sinus rhythm. These three scenarios were tested at an acceleration factor of 12.5. The fourth scenario accommodates for low temporal resolution training data, where the temporal resolution of the reconstructions is 5 times greater than the training data. This scenario achieved an effective acceleration of 62.5 using a radial undersampling mask.

Result and Discussion

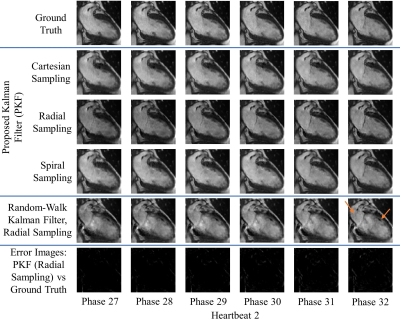

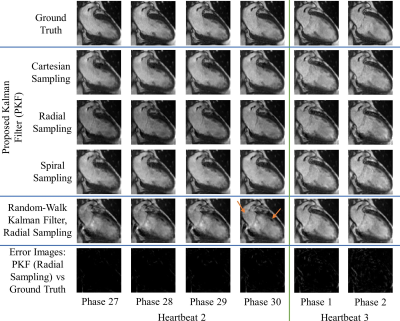

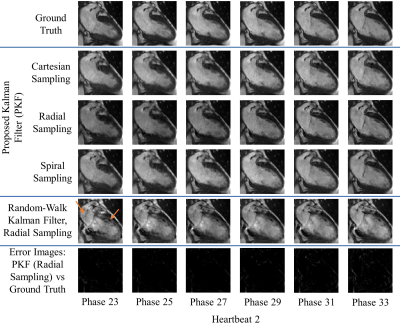

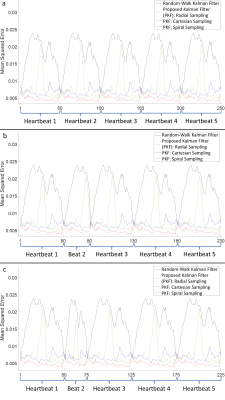

Figures 1-3 demonstrate excellent reconstruction fidelity compared to the random-walk Kalman filter 3,4. Figure 4 demonstrates MSE convergence for scenarios 1-3. Figure 5 demonstrates the ability to reconstruct at a higher temporal resolution than the training data while ensuring MSE convergence. Acceleration factors were chosen such that the MSE remained well below that of the random-walk Kalman filter. Overall, radial sampling was the most robust due to repeated sampling of low frequency k-space. However, the MSE for radial showed little improvement, reminding us of the dichotomy between what our eyes perceive as “acceptable” versus the MSE.Lastly, reconstruction fidelity is tied to our estimation of $$$f(x_{t-1})$$$; inaccurate estimates may cause divergence 5. Spikes in the MSE graph serve as a reminder (not an indicator) of this fact. To facilitate estimation of $$$f(x_{t-1})$$$, one must ensure that the training set is representative of the test set, cardiac phase estimation is robust, patient motion is compensated, and noise is properly dealt with.

Conclusion

We have demonstrated an algorithm that yields high-quality reconstructions, is adaptable to irregular cardiac dynamics, guarantees reconstruction quality, enables flexible undersampling, does not require re-binning, and can achieve a maximum acceleration factor of 62.5.Acknowledgements

The authors thank Professor Ravi Adve and Professor Raymond Kwong for fruitful discussions and guidance on Kalman filtering and statistical modeling. The authors thank the following funding agencies for support: A.D.C. is funded by an Ontario Graduate Scholarship. H-L.M.C. is supported by a Natural Sciences & Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) Discovery Grant (grant #2019-06137), Canadian Institutes of Health Research (grant #PJT 175131), and Canada Foundation for Innovation/Ontario Research Fund (grant #34038).References

1. Curtis, A. D. & Cheng, H. M. Primer and Historical Review on Rapid Cardiac <scp>CINE MRI</scp>. Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging 55, 373–388 (2022).

2. Kay, S. M. Fundamentals of Statistical Signal Processing (III): Practical Algorithm Development. Prentice Hall (2013).

3. Feng, X., Salerno, M., Kramer, C. M. & Meyer, C. H. Kalman filter techniques for accelerated Cartesian dynamic cardiac imaging. Magn Reson Med (2013) doi:10.1002/mrm.24375.

4. Sümbül, U., Santos, J. M. & Pauly, J. M. Improved time series reconstruction for dynamic magnetic resonance imaging. IEEE Trans Med Imaging (2009) doi:10.1109/TMI.2008.2012030.

5. Jwo, D. J. & Cho, T. S. A practical note on evaluating Kalman filter performance optimality and degradation. Appl Math Comput 193, (2007).

Figures