3079

Water/Fat separation with spatio-temporal EPI-based acquisition and reconstruction in body imaging1Department of Bioengineering, Stanford University, Stanford, CA, United States, 2Department of Radiology, Stanford University, Stanford, CA, United States, 3Department of Electrical Engineering, Stanford University, Stanford, CA, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Image Reconstruction, Image Reconstruction

Water/fat separation is a reliable fat suppression technique. However, it is challenging in EPI-based imaging due to the large displacement along phase-encoding direction. We demonstrate the artifacts resulting from the poor-conditioning reconstruction of water/fat separation with EPI-based acquisition in body imaging. As a solution, unlike conventional multi-echo acquisition methods, our approach encodes the spectral components (water/fat) by acquiring and reconstructing the spatial and echo-time dimensions jointly. EPTI sampling trajectories and water/fat masking were used to improve the conditioning of the reconstruction. Phantom and in vivo (brain and breast) experiments were performed to show both results and limitations of this approach.Introduction

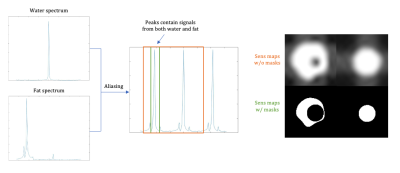

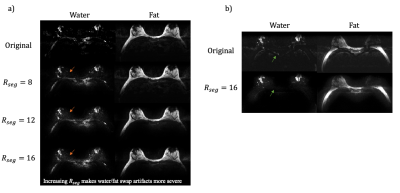

Echo planar imaging (EPI) is a widely-used, high-speed imaging technique. However, one drawback of EPI is the low effective bandwidth along the PE direction, which results in image blurring and distortion, as well as severe chemical shift displacement artifacts that also complicate parallel imaging. Conventional fat suppression methods, such as water-selective excitation1 and fat saturation pulses2, are sensitive to field inhomogeneities, which can potentially cause residual fat or loss of water signal in the images.Water/fat separation takes advantage of the phase difference between water and fat among multiple echo times to robustly separate frequency components, with some application to EPI-based sequences. Hu et al. separated water/fat signals using the intrinsic multi-echo acquisition of PSF-EPI3. The main challenge of this problem is its conditioning. When data is undersampled in both ky and t (echo time) dimensions, aliasing happens in both images and the frequency spectrum, causing the water and fat spectra to overlap (Fig.1). The reconstruction problem then becomes poorly-conditioned at these locations, leading to water/fat swap artifacts.

To characterize and resolve poor-conditioning problems, we viewed the problem in the x-y-f domain, using a spatio-temporal (temporal=echo time) joint acquisition and reconstruction method, demonstrating the problem in both phantom and in vivo experiments.

Methods

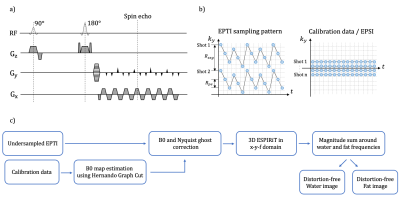

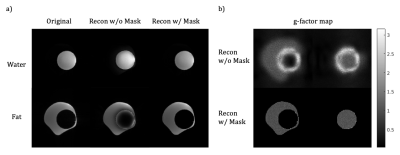

Echo planar time-resolved imaging (EPTI) was used as data acquisition strategy, which is a spatio-temporal CAIPI sampling trajectory4. The sequence diagram and sampling pattern with calibration dataset in ky-t space are shown in Figure 2a-b. Using repeated sampling of phase-encoding lines at different echo times with an EPI readout train, spectral components are encoded and can be separated by Fourier transform along the time dimension. The water/fat separation problem then becomes de-aliasing in the frequency domain. We applied 3D ESPIRiT5 to reconstruct the undersampled data in the x-y-f domain jointly. Off-resonance (B0 variation) was estimated by Hernando’s graph cut6 approach using calibration data and corrected before 3D ESPIRiT. A flowchart of the proposed method is shown in Figure 2. To improve the conditioning, we applied water/fat masks (generated by the graph cut method) to sensitivity maps.Acquisitions were performed at 3T (Signa Premier, GE Healthcare). Echo planar spectroscopic imaging (EPSI)7 was used to acquire fully sampled in kx-ky-t data on a water/fat phantom using an 8-channel head coil. Scan parameters: TR=3000ms, TE=65ms, acquisition matrix=128x128, echo-train length(ETL)=64, readout bandwidth=±165kHz, echo spacing(ESP)=0.78ms. Data were retrospectively undersampled uniformly in time and ky with Rt=3, Rpe= 2. Low-resolution calibration data was extracted retrospectively from the fully sampled data with 32 ky lines. g-factor maps were calculated using pseudo multiple replicas8 with the number of iterations=50.

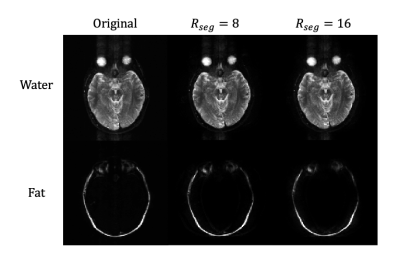

Brain and breast datasets were acquired on healthy volunteers with a fully sampled EPSI sequence following IRB approval and informed consent. Brain scans was performed using a 16-channel head coil with parameters: TR=2000ms, TE=68ms, acquisition matrix=128x128, ETL=64, readout bandwidth=±165kHz, ESP=0.82 ms. Retrospectively applied EPTI acceleration factors were: Rseg=[16,8], Rpe=4. N_ky_acs=32.

A breast scan was performed using a 16-channel breast coil with same parameters as above, except acquisition matrix 192 x 192, Rseg = [16,12,8]. An additional set of breast data was acquired with ASPIR fat saturation using the same scan parameters on the same volunteer.

Results

The comparison between water and fat only phantom images reconstructed with and without applying masks on sensitivity maps and the fully sampled data are demonstrated in Figure 3a.Results of brain and breast experiments are shown in Figure 4 & 5.

Discussion

In this work, we experimented with water/fat separation in EPI-based acquisition. Fat/water swap artifacts that result from poor conditioning of the reconstruction were demonstrated by both phantom and in vivo experiments. The problem becomes even more severe in body imaging since voxels often contain both water and fat. One solution is to apply water/fat masks to the respective spectral sensitivity maps, which improves the conditioning by increasing the accuracy of sensitivity information. However, this method is only applicable to conditions that have water and fat clearly separated (e.g., phantom and brain).Though the water-fat swap artifacts caused by bad conditioning could not be fully resolved in body imaging, an in vivo experiment in the breast with fat-saturation shows a more reliable water/fat separation result. Due to the severe B0 field inhomogeneity in the body, the fat-sat pulse could fail in suppressing fat signal. The method proposed above could be used to remove the residual fat in the images. The next step of this project is to try a sampling pattern with more randomness in both phase-encoding and time dimensions to further prevent from poor-conditioning problem and integrate it with body diffusion imaging.

Overall, we have characterized the problem of water/fat separation in EPI, which causes often subtle failure artifacts. Both masking and the use of fat-saturation can improve this problem. While not perfect, this approach is a substantial improvement to fat-saturated EPI, as it corrects the fat/water displacement artifacts (which often cause residual aliasing in parallel imaging). Additionally, this method produces distortion-free images that can ultimately enable diffusion-weighted imaging to be aligned with other sequences.

Conclusion

Water/fat separation can be performed using EPTI sampling pattern and spatio-temporal joint reconstruction, to avoid the distortion and fat/water displacement artifacts in EPI.Acknowledgements

NIH R01-EB009055References

1. Kaldoudi E, Williams SCR, Barker GJ, Tofts PS. A chemical shift selective inversion recovery sequence for fat-suppressed MRI: Theory and experimental validation. Magnetic Resonance Imaging 1993;11:341–55. doi:10.1016/0730-725x(93)90067-n.

2. Meyer CH, Pauly JM, Macovskiand A, Nishimura DG. Simultaneous spatial and spectral selective excitation. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine 1990;15:287–304. doi:10.1002/mrm.1910150211.

3. Hu Z, Wang Y, Dong Z, Guo H. Water/fat separation for distortion‐free EPI with point spread function encoding. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine 2019;82:251–62. doi:10.1002/mrm.27717.

4. Wang F, Dong Z, Reese TG, Bilgic B, Katherine Manhard M, Chen J, et al. Echo planar time-resolved imaging (EPTI). Magnetic Resonance in Medicine 2019; 81:3599–615. doi:10.1002/mrm.27673.

5. Uecker M, Lai P, Murphy MJ, Virtue P, Elad M, Pauly JM, et al. Espirit-an eigenvalue approach to autocalibrating parallel MRI: Where sense meets grappa. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine 2013; 71:990–1001. doi:10.1002/mrm.24751.

6. Hernando D, Kellman P, Haldar JP, Liang Z-P. Robust water/fat separation in the presence of large field inhomogeneities using a graph cut algorithm. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine 2009. doi:10.1002/mrm.22177.

7. Mansfield P. Spatial mapping of the chemical shift in NMR. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine 1984; 1:370–86. doi:10.1002/mrm.1910010308.

8. Robson PM, Grant AK, Madhuranthakam AJ, Lattanzi R, Sodickson DK, McKenzie CA. Comprehensive quantification of signal-to-noise ratio and g-factor for image-based and k-space-based parallel imaging reconstructions. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine 2008; 60:895–907. doi:10.1002/mrm.21728.

Figures