3078

Accelerated 3D dynamic upper-airway MRI in naturally sleeping obstructive sleep apnea patients.

Wahidul Alam1, Junjie Liu2, and Sajan Goud Lingala1,3

1Roy J. Carver Department of Biomedical Engineering, University of Iowa, iowa city, IA, United States, 2Department of Neurology, University of Iowa, iowa city, IA, United States, 3Department of Radiology, University of Iowa, Iowa city, IA, United States

1Roy J. Carver Department of Biomedical Engineering, University of Iowa, iowa city, IA, United States, 2Department of Neurology, University of Iowa, iowa city, IA, United States, 3Department of Radiology, University of Iowa, Iowa city, IA, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Image Reconstruction, Head & Neck/ENT

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is characterized by breathing-related obstructions of the upper airway during sleep. In this work, we develop a motion resolved extra-dimension sparsity-based approach to resolve the kinematics of upper-airway in OSA during natural sleep. This approach is demonstrated on two adult OSA patients: one undergoing a Bi-directional positive airway pressure therapy during MRI scanning, and one without therapyPURPOSE

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is characterized by breathing-related obstructions of the upper airway during sleep. Dynamic MRI of the upper-airway during OSA is a promising approach to safely visualize the spatial pattern of collapse. Current 2D schemes can achieve temporal resolutions of up to 200 ms, but are restricted to sequentially acquiring the 2D slices [1-2]. Finite difference based spatio-temporal constraints have shown potential to accelerate dynamic volumetric, and simultaneous multi-slice upper-airway MRI [3-4]. However, these constraints tend to introduce motion blurring when modeling irregular motion, and may be susceptible to motion artifacts in OSA [3-4]. In this work, we develop a motion resolved extra-dimension sparsity-based approach to resolve the kinematics of upper-airway in OSA during natural sleep. This approach is demonstrated on two adult OSA patients: one undergoing a Bi-directional positive airway pressure therapy during MRI scanning, and one without therapy.METHODS

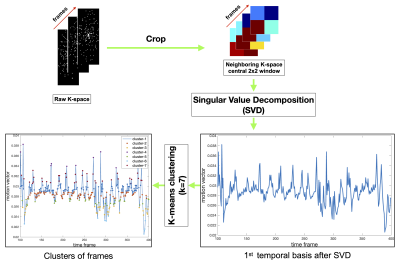

Experiments were performed on a GE 3 Tesla Premier scanner. A Cartesian based 3D gradient-echo sequence was modified such that the ky-kz sampling traversal followed a variable density random view order [5]. This was designed to achieve incoherent distribution of the ky-kz samples for a desired time resolution of ~380 ms/frame at an isotropic (2mm)3 spatial resolution for FOV ranging between 20-24 cm along the anterior-posterior; superior-inferior directions, and 8 cm along the left-right direction. Flip angle was 50; TR was 2.6ms. Two adult patients diagnosed with OSA were scanned. The first patient was scanned with a head-neck coil. Prior to scanning, the second patient wore a MR compatible nasal mask for simultaneous bi-directional positive airway pressure therapy (Bi-PAP) during MRI scanning. The nasal mask was connected via a long tubing to a Resmed’s AirCurve 10 VAuto device (in the operator’s room), which controlled the supplied positive airway pressure to the patient. Bi level pressure settings of (13/8) cm H20 and (10/5) cm H20 were provided to the second patient. The numerator and denominator respectively represent the pressure settings during patient’s inhalation and exhalation. Both the patients fell asleep as confirmed by simultaneously recorded physiological signals (eg. change in O2 saturation level). For reconstruction, we first extracted the central (2x2) k-space patch for every time frame for all the coils, and performed a singular-value-decomposition along the time dimension. The first significant component revealed the major motion dynamics in the dataset, and acted as a navigator signal. We performed k-means clustering to cluster this navigator signal into nbins, where each bin share similar motion state (see Fig. 1). The original raw 5D k-space (of size nkx, nky, nkz, ncoils, nframes) was sorted into a 6D k-space dataset (nkx, nky, nkz, ncoils, nbins, nframes_per_bin) were nbins represent the number of bins that represent different respiratory motion states, and nframes_per_bin represents an auxiliary sixth dimension that contain the number of time phases in each motion state.We then apply a patch based locally low rank and spatio-temporal sparsity based SENSE reconstruction scheme where the constraints are enforced on the auxiliary motion dimension of the imaging dataset. Regularization parameters were set to 0.01 and 0.3 respectively for the spatial, temporal finite difference sparsity, and 0.2 for the locally low rank terms. With the goal of identifying the pattern of airway collapse in the first patient without therapy, we visually assessed the dynamics of the upper-airway shaping. With the goal to quantitate the change in the airway aperture lumen size for the second patient undergoing BiPAP therapy, we manually segmented the upper-airway in a representative velopharynx slice and contrasted the dynamics across pressure settings. Segmentation was performed by a graduate student researcher with experience in image processing within the Slicer software.RESULTS

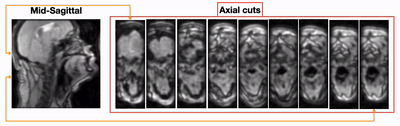

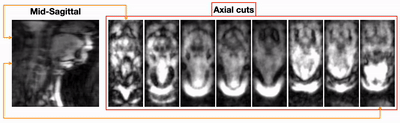

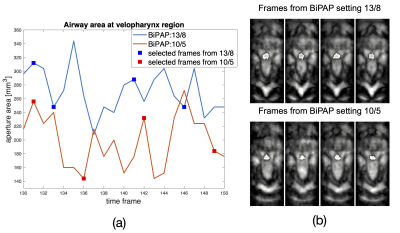

Figure 2 shows the 3D volumetric upper-airway dynamic reconstruction in the first OSA patient without therapy. Shown are a representative mid-sagittal view, and few axial slices from the velopharynx to the hypopharynx. The visualization demonstrates concentric collapse (i.e, collapse in both anterior-posterior; and lateral directions) across the entire upper-airway. Figure 3 shows the reconstructions for the second OSA patient undergoing BiPAP therapy at the 13/8 pressure setting. This subject had a smaller airway opening due to a large sized tongue. However, the airway was patent due to the BiPAP therapy, and experienced dynamic change in the lumen size as a function of the supplied pressure settings. Figure 4 finally shows a representative velopharynx axial cut for the BiPAP settings of 13/8 and 10/5. We observe the reconstructions to faithfully depict the expected pattern of the airway aperture opening to be narrower in the 10/5 setting when compared to 13/8 setting.CONCLUSION

We demonstrated an accelerated motion resolved volumetric MRI scheme to capture the dynamics of upper-airway shaping in OSA. Our preliminary findings show that our approach is capable to delineate the spatial pattern of airway collapse in untreated OSA, and quantitate the change in lumen size in patients undergoing BiPAP therapy. This study involved time consuming manual segmentation. Future work will include applying efficient semi-automatic segmentation to quantitate the lumen size across the entire airway, and further estimating the upper-airway’s compliance based on the knowledge of the pressure experienced by the airway.Acknowledgements

This work was conducted on an MRI instrument funded by 1S10OD025025-01.References

- Huon, L. K., Liu, S. Y. C., Shih, T. T. F., Chen, Y. J., Lo, M. T., & Wang, P. C. (2016). Dynamic upper airway collapse observed from sleep MRI: BMI-matched severe and mild OSA patients. European Archives of Oto-Rhino-Laryngology, 273(11), 4021-4026.

- Feng, Y., Keenan, B. T., Wang, S., Leinwand, S., Wiemken, A., Pack, A. I., & Schwab, R. J. (2018). Dynamic upper airway imaging during wakefulness in obese subjects with and without sleep apnea. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine, 198(11), 1435-1443.

- Kim, Y. C., Lebel, R. M., Wu, Z., Ward, S. L. D., Khoo, M. C., & Nayak, K. S. (2014). Real‐time 3D magnetic resonance imaging of the pharyngeal airway in sleep apnea. Magnetic resonance in medicine, 71(4), 1501-1510.

- Wu, Z., Chen, W., Khoo, M. C., Davidson Ward, S. L., & Nayak, K. S. (2016). Evaluation of upper airway collapsibility using real‐time MRI. Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging, 44(1), 158-167.

- Cheng, J. Y., Hanneman, K., Zhang, T., Alley, M. T., Lai, P., Tamir, J. I., ... & Vasanawala, S. S. (2016). Comprehensive motion‐compensated highly accelerated 4D flow MRI with ferumoxytol enhancement for pediatric congenital heart disease. Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging, 43(6), 1355-1368.

Figures

Figure 1: The pipeline of extracting the navigator data for self-gated motion resolved sparsity based reconstruction. 2x2 central k-space at every time frame is fully sampled. A SVD along the time dimension reveals the significant motion in the dataset. Shown here is the first significant temporal basis, which forms the navigator signal. A k-mean clustering is applied on this navigator signal to cluster and resort the k-space to similar motion states prior to reconstruction.

Figure 2:(animation) Dynamic volumetric of upper-airway collapse in the first naturally sleeping OSA patient. Shown here is a mid-sagittal slice and few axial cuts from the velopharynx to the hypopharynx region. Note the collapse is largely identified at the velopharynx region. Furthermore, the collapse is concentric in nature (i.e, collapse occurring along both anterior-posterior and lateral directions).

Figure 3:(animation) Dynamic volumetric of upper-airway collapse in the second naturally sleeping OSA patient. This patient was also simultaneously under the BiPAP therapy. This figure shows the representation when the BiPAP pressure settings were 13/8 H20 cm. Note that this subject had a larger tongue volume anatomy, and thus had a narrower airway opening. This opening airway was maintained due to the BiPAP therapy. The change in the airway lumen size occurs based on the supplied pressure settings.

Figure 4: Comparison of airway lumen size at the velopharynx with BiPAP pressure settings of 13/8 and 10/5 H20cm. Note with the 10/5setting, the airway lumen size has a narrower opening compared to the airway lumen size with the 13/8setting.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.58530/2023/3078