3062

Deep Learning-based Automatic Perfusion Phase Identification for Dynamic T1-weighted Liver MRI

Robert Grimm1, Malte Müller2, Cornelius Jacob1, Sabine Mollus1, Christian Tietjen3, Moon Hyung Choi4, Kazuki Oyama5, Thomas Weikert6, Andrew D Hardie7, Jeong Hee Yoon8, Heinrich von Busch3, Gregor Thoermer1, and Volker Daum2

1MR Application Predevelopment, Siemens Healthcare GmbH, Erlangen, Germany, 2Chimaera GmbH, Erlangen, Germany, 3Digital and Automation, Siemens Healthcare GmbH, Erlangen, Germany, 4Eunpyeong St. Mary’s Hospital, Catholic University of Korea, Seoul, Korea, Republic of, 5Department of Radiology, Shinshu University Hospital, Nagano, Japan, 6Department of Radiology, Universitätsspital Basel, Basel, Switzerland, 7Radiology and Radiological Science, Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, SC, United States, 8Seoul National University Hospital and College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea, Republic of

1MR Application Predevelopment, Siemens Healthcare GmbH, Erlangen, Germany, 2Chimaera GmbH, Erlangen, Germany, 3Digital and Automation, Siemens Healthcare GmbH, Erlangen, Germany, 4Eunpyeong St. Mary’s Hospital, Catholic University of Korea, Seoul, Korea, Republic of, 5Department of Radiology, Shinshu University Hospital, Nagano, Japan, 6Department of Radiology, Universitätsspital Basel, Basel, Switzerland, 7Radiology and Radiological Science, Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, SC, United States, 8Seoul National University Hospital and College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea, Republic of

Synopsis

Keywords: Data Analysis, Machine Learning/Artificial Intelligence

A deep learning-based approach for automatic identification of the perfusion phases in dynamic T1-weighted liver MRI is presented. First, an encoder model combined with two dense layers was trained to classify each image into pre-contrast, arterial, portal-venous, late, or hepatobiliary phase. In a second pass, classification errors are detected and adjusted, based on the expected occurrence order and relative timing to the arterial phase. The AI model reached sensitivities of 67% to 99%. Most common mis-classifications were confusions of the portal-venous or late phase with the adjacent phases. By the rule-based adjustments, the classification performance was raised to >95% accuracy.Introduction

Dynamic T1-weighted MR imaging is an indispensable technique for the detection and differential diagnosis of focal liver lesions. It typically comprises repeated imaging in four or five phases1: before contrast agent administration (pre-contrast), about 20 seconds post-injection (arterial), 70 seconds post-injection (portal-venous), 3 minutes post-injection (late), and, with hepatocyte-specific contrast agents, 20 minutes post-injection (hepatobiliary phase). For immediate quality-checking after acquisition, for post-processing tasks, as well as for consistent visual presentation to the radiologist, it is desirable to know which series in a patient study correspond to which of the above-mentioned phases. However, it can be non-trivial to identify the perfusion phase from DICOM attributes unless specific series descriptions are assigned to the individual acquisitions2,3,4. In the following, a fully automatic method is proposed that predicts the perfusion phase based on image contents, with the help of a deep learning model. By additional rule-based adjustments which exploit the temporal image acquisition order and relative timing, mis-classifications by the image-based approach can be effectively detected and corrected, significantly improving the classification performance.Methods

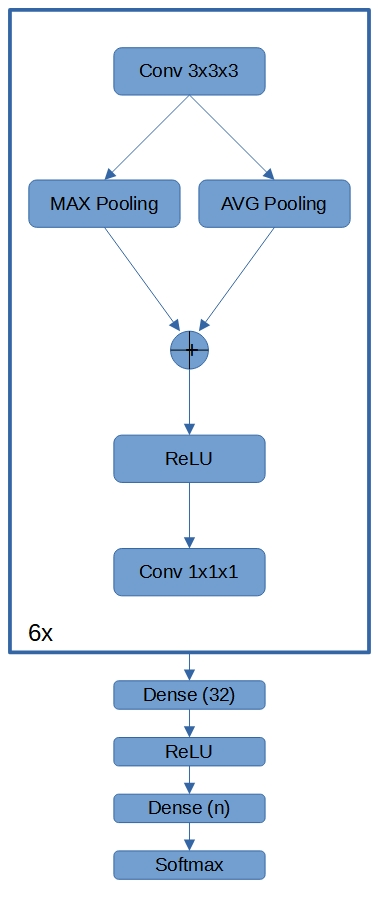

A total number of 4692 series from 947 liver MRI examinations on 744 patients was pooled from four institutions. Axial T1-weighted imaging of the liver was performed with 3D gradient-echo pulse sequences using the respective routine imaging protocols. For the first experiment, an independent test set was formed by separating the data from 131 patients, including a balanced representation of contrast agents (hepatobiliary and extracellular) and magnetic field strengths (3T and 1.5T). Ground truth labels of the perfusion phase were derived either from the series description, where available, or inferred from the acquisition order and timing of the acquisitions, followed by final human review of the assignment. Note that the order-based derivation had to be tailored to every institution, as some hospitals used e.g. acquisition of multiple arterial or delayed phase acquisitions and, even within each hospital, different scan protocols often were utilized.As pre-processing, the data was reformatted to a common spacing and FOV of 1.1 x 1.1 x 3.0 mm3 at 256 x 256 x 72 voxels. A deep learning model, shown in Fig. 1, was implemented using TensorFlow/Keras. It consists of an encoder serving as a feature extractor and a subsequent classifier. The encoder is built from six sequential blocks, each of which consists of a convolution with a kernel of size 3, a rectified linear unit activation, two parallel pooling operations (max pooling and average pooling) and a final convolution with kernel size 1 on the concatenated outputs on the pooling layers. The classifier consists of one dense layer of 32 units and the final dense layer of five units for the different output classes (pre-contrast, arterial, portal-venous, late, hepatobiliary). The model was optimized using ADAM and five-fold cross validation. To construct the final model, the data from all five folds was pooled. The classification performance of each phase was evaluated.

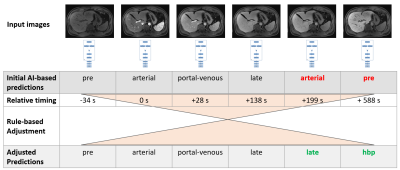

On top of the independent phase classification on individual series level, an additional rule-based adjustment of classifications was performed, based on the following requirements applied within each study:

- The first acquired series is assumed to be pre-contrast phase.

- Classifications can only appear in the monotonous order pre-contrast, arterial, portal-venous, late, hepatobiliary. Phases may be repeated, but the order may not be violated.

- Classifications have to be consistent with pre-specified timing intervals (portal-venous phase 19-100 s after arterial, late phase 101-300 s after arterial, hepatobiliary phase > 300 s after arterial).

Results

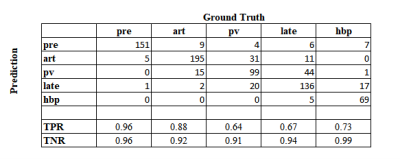

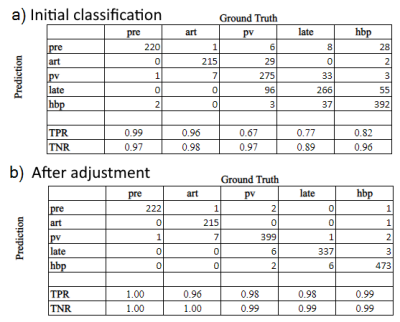

The confusion matrix for the first experiment on independent phase classification performance is shown in Fig. 3. The true positive rate (TPR) or sensitivity ranged from 64% to 96%, while the true negative rate (TNR) or specificity was 91-99%. The most common confusions were mis-classification of portal-venous images as arterial or late, and arterial or late-phase images as portal-venous.The initial series-level confusion matrix for the second experiment is shown in Fig. 4a. Similar to the previous results, the TPR ranged from 67% (portal-venous phase) to 99% (pre-contrast phase), with most mis-classifications between portal-venous or late phase. By the additional rule-based sanity checking and readjustment, most mis-classifications could be resolved (Fig. 4b).

Discussion & Conclusion

The feasibility of image-based phase identification for dynamic T1-weighted liver imaging was proven. The proposed method can help identifying the perfusion phase in case the information cannot be reliably deduced from the DICOM series description or acquisition order, e.g., when heterogenous scan protocols are used. While the trained model still showed room for potential improvement, in particular for differentiating portal-venous and late phases, nearly all mis-classifications could be detected and corrected by additionally taking advantage of the temporal order and expected timing of the phases. In conclusion, the proposed two step approach, combining artificial intelligence with simple logical rules, allows for robust classification of dynamic liver phases.Acknowledgements

No acknowledgement found.References

- Low R, “MR Imaging of the Liver Using Gadolinium Chelates”, Magn. Reson. Imaging Clin. N. Am. 2001;9(4):717-743. doi: 10.1016/S1064-9689(21)00271-3.

- Vieira de Mello JP et al., "Deep Learning-based Type Identification of Volumetric MRI, doi: Sequences," 2020 25th International Conference on Pattern Recognition (ICPR), 2021, pp. 1-8. doi: 10.1109/ICPR48806.2021.9413120.

- Ranjbar S et al., “A Deep Convolutional Neural Network for Annotation of Magnetic Resonance Imaging Sequence Type”. J Digit Imaging. 2020 Apr;33(2):439-446. doi: 10.1007/s10278-019-00282-4

- Feng L et al., “GRASP-Pro: imProving GRASP DCE-MRI through self-calibrating subspace-modeling and contrast phase automation”. Magn Reson Med. 2020 Jan;83(1):94-108. doi: 10.1002/mrm.27903.

Figures

Fig. 1 Schematic drawing of the Deep Learning model architecture. The encoder is formed by six blocks of convolution, concatenation of parallel pooling operations, a rectified linear unit activation and final convolution operation. The result is fed into a dense classification layer with 32 units and the final dense layer with five units for the different output classes (pre-contrast, arterial, portal-venous, late, hepatobiliary phase).

Fig. 2 Overview of the proposed method, for an example study containing pre-contrast, arterial, portal-venous phase, two late phases, and hepatobiliary phase. The input series are first individually classified by a deep learning-based model. In a second step, the predictions are adjusted based on a layer of additional rules, considering the study-level context, order of appearance and timing relative to the arterial phase. This allows, e.g., detection and correction of the error when a late and hepatobiliary phase were mis-classified as arterial and pre-contrast, respectively.

Fig. 3 Confusion matrix for classification of individual phases on balanced multi-site testing cohort (Experiment 1).

Fig. 2a) Confusion matrix for independent classification of phases on single-site study level testing cohort (Experiment 2).

Fig. 2b) Most mis-classifications are resolved by additionally applying the rule-based adjustment that takes the temporal order and relative timing of series in a study into account.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.58530/2023/3062