3060

The impact of naproxen on Cerebral Blood Flow in preclinical Alzheimer’s disease1Physics, Concordia University, Montreal, QC, Canada, 2Centre de Recherche de l’Institut de Cardiologie de Montr´eal, Montreal, QC, Canada, 3Sunnybrook Research Institute, Toronto, ON, Canada, 4Douglas Mental Health Institute, Montreal, QC, Canada, 5Concordia University, Montreal, QC, Canada, 6PERFORM Centre, Concordia University, Montreal, QC, Canada

Synopsis

Keywords: Data Processing, Alzheimer's Disease

Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) is the most common form of dementia and displays a long preclinical phase. The use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) in this phase has a protective effect and decreases the risk of developing AD cross-sectionally. However, the effects of NSAIDs therapy long-term on cerebral hemodynamics in this early phase is unclear. This is the first study to assess whether longitudinal use of NSAIDs (i.e., naproxen) has an impact on cerebral blood flow, and whether this is associated with a change in cognition and/or cerebrospinal fluid markers.Introduction

AD has a long preclinical phase prior to the manifestation of cognitive decline. There is compelling evidence to suggest that AD-related changes can be detected in the early phase, with several biomarkers beginning to change. One of the most commonly studied biomarkers is Amyloid beta concentration in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), which has been shown to decrease in early AD stages1. In addition, early changes to Cerebral Blood Flow (CBF) have been shown to occur years before AD, and prior to CSF amyloid decreases2,3,4. Thus, the combined use of CBF and CSF amyloid is a promising avenue to study early disease brain changes.AD currently has no cure, but some preventative interventions could help slow the progression of the disease. Among the different types of drugs, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAID) have shown promise for prevention of AD. Longitudinal studies demonstrate that taking NSAIDs decreases the risk of AD during the preclinical phase of the disease (i.e., before cognitive decline), though the specific impact of NSAIDs on the brain and AD biomarkers is still unclear5,6,7,8. Here, we investigate the effect of naproxen (an NSAID) on CBF and CSF biomarkers over a period of two years to understand the influence of naproxen on brain physiology and AD pathology.

Methods

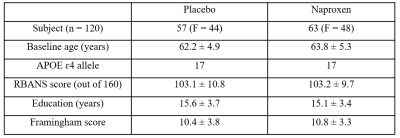

Data acquisition was completed in 120 participants who were at an increased risk of developing AD based on familial and genetic information. All participants were then randomized to take naproxen sodium 220 mg twice daily or placebo (Table. 1 for demographics). Pseudo-continuous arterial spin labelling (pCASL) and structural data were collected annually, and a lumbar puncture was performed at each timepoint to determine amyloid concentrations in CSF. All participants also completed an extensive neuropsychological test battery at baseline and all other time points to track cognitive changes9.Preprocessing was performed and resting CBF was quantified10 using FSL and MATLAB. All CBF maps were registered to native T1 images in subject space and then to the group space, and the final group space image was then registered to MNI space using ANTS11. Linear Mixed Model effects (LMMs) with random slopes and intercepts for longitudinal analysis were fitted to investigate the effect of naproxen on longitudinal changes in CBF and CSF biomarkers with age, sex, APoE ε4 status, education, and vascular risk factor as the covariates.

Results

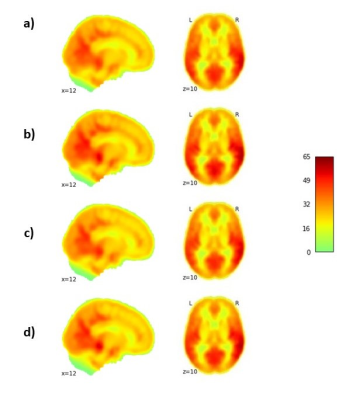

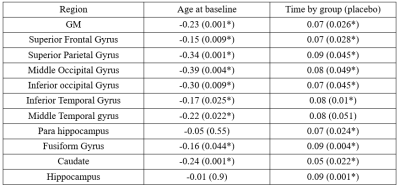

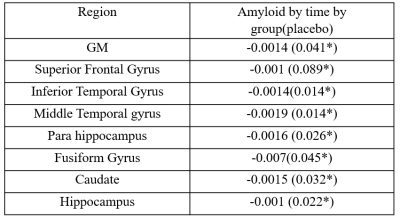

LMMs revealed a significant increase in CBF in the placebo group compared to the naproxen group across the two years (p < 0.05). The rate of CBF increase was significant in the regions listed in Table. 2. Figure. 1 also shows the changes in CBF in grey matter in both groups. To investigate whether these differences are associated with amyloid changes in the brain, LMMs were also fitted to the significant regions by adding amyloid changes as the predictor. Results revealed a significant negative association across time between CSF amyloid and CBF in all brain regions except the occipital and parietal regions (Table. 3).Discussion

Our results revealed hyperperfused regions in the placebo group only. Similar patterns of hyperperfusion in the years prior to AD development have previously been observed and have been interpreted as a compensatory process for metabolic changes12. This process is thought to precede a phase where hyperperfusion reaches an inflection point before declining during in cognitive impairment and AD14. Moreover, these regions have been shown to be associated with cognitive decline in structural and functional outcomes13.Some of the observed effects in the placebo group may be related to amyloid accumulation in the brain, since we observed a significant negative association between CBF increase and amyloid change in CSF only in the placebo group. It is important to note that lower amyloid in CSF is associated with greater amyloid in the brain, so that our results indicate that higher amyloid in the brain is associated with higher perfusion. This association, when cognition is preserved, is consistent with the hypothesis that it represents a compensatory response to amyloid accumulation14,15, and in line with results in healthy older adults showing hyperperfusion in individuals with higher amyloid deposition 14. This compensatory response has been observed in regions that have previously been shown to be more vulnerable in AD13,14. To our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate the impact of naproxen on CBF and AD biomarkers, though previous studies showed the protective role of NSAID in age-related brain structural changes7,8. Other studies are needed to assess the clinical significance of these findings on the incidence of cognitive impairment and AD. Future studies could also investigate the effects of naproxen on upstream cerebrovascular markers, such as cerebrovascular reactivity to better understand the exact effect of naproxen on the AD development progress.

Conclusion

Our results revealed a longitudinal CBF increase in the placebo group compared to the naproxen group. This increase is associated with greater amyloid beta accumulation, highlighting the positive effects of NSAIDS on brain health in individuals at high risk to develop AD.Acknowledgements

Data used in preparation of this article were obtained from the Pre-symptomatic Evaluation of Novel or Experimental Treatments for Alzheimer’s Disease (PREVENT-AD) program (https://douglas.research.mcgill.ca/stop-ad-centre), data release 5.0 (November 30, 2017). A complete listing of PREVENT-AD Research Group can be found in the PREVENT-AD database: https://preventad.loris.ca/acknowledgements/acknowledgements.php?date= [2019-06-03]. The investigators of the PREVENT-AD program contributed to the design and implementation of PREVENT-AD and/or provided data but did not participate in analysis or writing of this report. The authors would also like to thank Heart and Stroke Foundation New Investigator Award and J.M. Barnett fellowship, and the Michal and Renata Hornstein Chair in Cardiovascular Imaging.References

1. Stomrud, E., Forsberg, A., Hägerström, D., Ryding, E., Blennow, K., Zetterberg, H., ... & Londos, E. (2012). CSF biomarkers correlate with cerebral blood flow on SPECT in healthy elderly. Dementia and geriatric cognitive disorders, 33(2-3), 156-163.

2. Camargo, Aldo, Ze Wang, and Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative. "Longitudinal cerebral blood flow changes in normal aging and the Alzheimer’s disease continuum identified by arterial spin labeling MRI." Journal of Alzheimer's Disease 81.4 (2021): 1727-1735.

3. Hansson, O., Buchhave, P., Zetterberg, H., Blennow, K., Minthon, L., & Warkentin, S. (2009). Combined rCBF and CSF biomarkers predict progression from mild cognitive impairment to Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiology of aging, 30(2), 165-173.

4. Wierenga, Christina E., Chelsea C. Hays, and Zvinka Z. Zlatar. "Cerebral blood flow measured by arterial spin labeling MRI as a preclinical marker of Alzheimer's disease." Journal of Alzheimer's Disease 42.s4 (2014): S411-S419.

5. In'T Veld, Bas A., et al. "Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs and the risk of Alzheimer's disease." New England Journal of Medicine 345.21 (2001): 1515-1521.

6. Anthony, J. C., et al. "Reduced prevalence of AD in users of NSAIDs and H2 receptor antagonists: the Cache County study." Neurology 54.11 (2000): 2066-2071.

7. Walther, K., Bendlin, B. B., Glisky, E. L., Trouard, T. P., Lisse, J. R., Posever, J. O., & Ryan, L. (2011). Anti-inflammatory drugs reduce age-related decreases in brain volume in cognitively normal older adults. Neurobiology of aging, 32(3), 497-505.

8. Bendlin, Barbara B., et al. "NSAIDs may protect against age-related brain atrophy." Frontiers in aging neuroscience 2 (2010): 35.

9. Tremblay-Mercier, Jennifer, et al. "Open science datasets from PREVENT-AD, a longitudinal cohort of pre-symptomatic Alzheimer’s disease." NeuroImage: Clinical 31 (2021): 102733.

10. Alsop, David C., et al. "Recommended implementation of arterial spin‐labeled perfusion MRI for clinical applications: a consensus of the ISMRM perfusion study group and the European consortium for ASL in dementia." Magnetic resonance in medicine 73.1 (2015): 102-116.

11. http://stnava.github.io/ANTs/

12. Beason-Held, Lori L., et al. "Changes in brain function occur years before the onset of cognitive impairment." Journal of Neuroscience 33.46 (2013): 18008-18014.

13. Bangen, Katherine J., et al. "Assessment of Alzheimer's disease risk with functional magnetic resonance imaging: an arterial spin labeling study." Journal of Alzheimer's Disease 31.s3 (2012): S59-S74.

14. Fazlollahi, Amir, et al. "Increased cerebral blood flow with increased amyloid burden in the preclinical phase of alzheimer's disease." Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging 51.2 (2020): 505-513.

15. Oh, Hwamee, et al. "Covarying alterations in Aβ deposition, glucose metabolism, and gray matter volume in cognitively normal elderly." Human brain mapping 35.1 (2014): 297-308.

16. Zhang, Heng, et al. "Cerebral blood flow in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis." Ageing Research Reviews 71 (2021): 101450.

Figures