3045

Decreased cholinergic nucleus 4 basal forebrain density is associated with disease progression in Alzheimer’s Disease.

Coreylyn A. deBettencourt1, Kirubel Kentiba1, Alexander Atalay2, Benjamin T. Newman3, John D. Van Horn4, and T. Jason Druzgal3

1University of Virginia School of Medicine, Charlottesville, VA, United States, 2University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA, United States, 3Radiology and Medical Imaging, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA, United States, 4Department of Psychology, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA, United States

1University of Virginia School of Medicine, Charlottesville, VA, United States, 2University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA, United States, 3Radiology and Medical Imaging, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA, United States, 4Department of Psychology, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Alzheimer's Disease, Alzheimer's Disease

Density of the cholinergic nuclei of the basal forebrain has been shown to be associated with disease and symptom progression in Parkinson’s Disease. This project was aimed at determining if there is a similar effect of these brain regions in predicting cognitive impairment and disease progression in Alzheimer’s Disease. By using a longitudinal multicenter dataset of Alzheimer's patients in the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI), we analyzed the relationship between grey matter density of cholinergic basal forebrain and disease progression. We demonstrated that patients with increased disease severity had significantly lower density in the cholinergic nuclei of the basal forebrain.Introduction

Degeneration of the cholinergic basal forebrain nuclei is a key feature of Parkinson’s Disease progression1. Due to its role supplying cholinergic innervation to the neocortex, basal forebrain degeneration can have severe and wide-ranging effects. Worsening symptoms of disease such as gait impairment, psychosis and impaired cognition are all associated with decreasing density in cholinergic nucleus 41,2,3. Basal forebrain density has also been implicated in Alzheimer’s Disease, especially in association with beta amyloid protein aggregates4. Additionally, Alzheimer’s Disease has been associated with basal forebrain cholinergic degradation in the setting of exacerbated age-related atrophy5. As both diseases are associated with dementia and their pathophysiology relates to basal forebrain densities, we predicted that cholinergic nucleus 4 would also have decreased density in patients with further disease progression in Alzheimer’s Disease.Methods

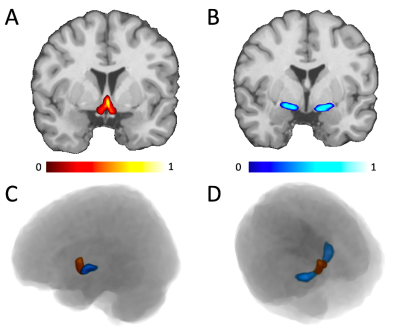

We gathered retrospective neuroimaging, clinical, and demographic longitudinal data from participants enrolled in the third series of the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI3)6. Participants were assessed and scanned annually over three to four years using a number of clinical, cognitive, and neuroimaging assessments. Individuals enrolled in the study were categorized into four groups based on their cognitive status. These groups split individuals with normal cognitive (CN) function from those diagnosed with significant memory concern (SMC), mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and those with Alzheimer’s disease (AD).In ADNI3, there were a total of 588 subjects with 1214 MRI scans. There were 159 CN subjects (271 scans), 161 SMC subjects (340 scans), 230 MCI subjects (526 scans), and 38 AD subjects (77 scans). To assess cholinergic basal forebrain density a voxel-based morphometric approach was used identically to previous work 1,3. This involved using the collected T1-weighted MP-RAGE images with isotropic voxels 1x1x1mm with an FOV 208x240x256mm, TE=60sec and TR=2300ms7. Images were preprocessed using N4 bias field correction implemented in ANTs8,9 and spatially normalized with the CAT12 toolbox implemented in SPM1210 in MATLAB (Mathworks, Natick, MA). Basal forebrain segmentations were used from the enhanced tissue probability map created by Lorio et al11 (Figure 1). Basal forebrain density was assessed in two bilateral segmentations containing cholinergic nuclei 1, 2, and 3, (Ch123) and a separate segmentation of cholinergic nuclei 4 (Ch4). Statistically, associations between gray matter density (GMD) of the two basal forebrain regions of interest and diagnosis group was determined at baseline and longitudinally using linear regression models that controlled for subject age, sex, and intracranial volume.

Results

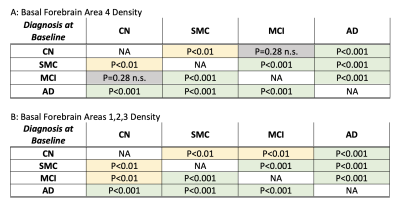

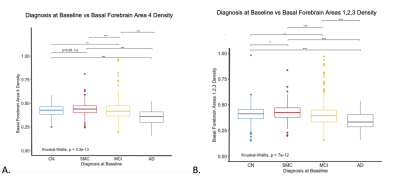

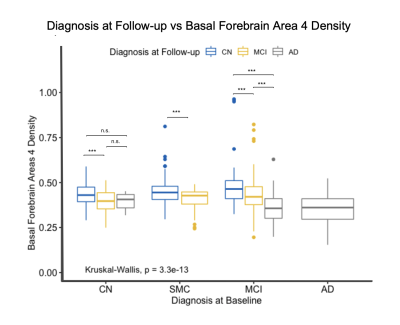

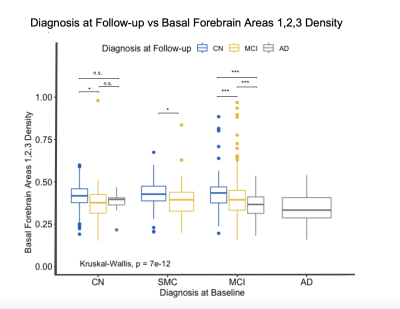

At baseline, Ch4 density was significantly decreased in AD patients compared to the CN, MCI, and SMC groups (Figure 3a). The MCI group was also found to have lower densities in Ch4 compared to the control group (for all cross-sectional results at baseline see Figure 2). Using the same model for Ch123, AD patients were also found to have significantly decreased Ch123 densities compared to CN, SMC, and MCI groups (Figure 3b). In these regions the SMC and MCI groups also had significantly lower densities compared to the CN group (Figure 2b).As the subjects were followed in the study, their diagnoses changed based on clinical assessment. By grouping subjects based on their diagnosis at baseline and analyzing changes in their basal forebrain densities with changing diagnosis at follow-up visits, we were able to look at how disease progression correlates with the basal forebrain GMD. Within the CN group, subjects that progressed to MCI had significantly lower densities in CH4 and CH123 compared to those that remained in the CN diagnosis (Figure 4, 5). Within the MCI group, those that progressed to AD had significantly lower densities in both CH4 and CH123 compared to those that either remained MCI or improved to CN at time of assessment (Figure 4, 5).

Discussion

As cholinergic basal forebrain densities predicted disease progression in Parkinson’s Disease, we hypothesized that decreased cholinergic nucleus 4 density would be associated with more severe disease in AD patients. We used a linear regression model that controlled for age, sex, and intracranial volume to analyze the relationship between density and disease severity both cross-sectionally at baseline and longitudinally. The AD patients were shown to have significantly lower Ch123 and Ch4 densities compared to all other disease groups (Figure 3). Additionally, the MCI group also had significantly lower Ch4 densities compared to the CN group and the MCI and SMC groups had significantly lower Ch123 densities compared to the CN group (Figure 3). While we expected a correlation specifically in Ch4, disease severity progression is likely linked to general basal forebrain function and nucleus density in both Ch4 and Ch123. We also wanted to look at how disease progression correlated with basal forebrain densities. By looking at diagnosis at follow-up, we were able to determine that subjects that progressed from CN to MCI and subjects that progressed from MCI to AD had significantly lower Ch4 and Ch123 densities (Figure 4, 5). This indicates that not only are these regions linked to disease severity but are also associated with disease progression based on follow-up diagnosis. Despite differences in pathogenesis and symptoms, there appears to be a common pattern of degeneration in the basal forebrain that is indicative of disease severity in both Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s diseases.Acknowledgements

No acknowledgement found.References

- Barrett, M. J., Sperling, S. A., Blair, J. C., Freeman, C. S., Flanigan, J. L., Smolkin, M. E., Manning, C. A., & Druzgal, J. (2019). Lower volume, more impairment: reduced cholinergic basal forebrain grey matter density is associated with impaired cognition in Parkison disease. Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry.

- Dalrymple, W. A., Huss D. S., Blair, J., Flanigan, J. L., Patrie, J., Sperling, S. A., Shah, B. B., Harrison, M. B., Druzgal, T. J., & Barrett, M. J. (2020). Cholinergic nucleus 4 atrophy and gait impairment in Parkinson’s disease. Journal of Neurology.

- Barrett, M. J., Blair, J. C., Sperling, S. A., Smolkin, M. E., & Druzgal, T. J. (2018). Baseline symptoms and basal forebrain volume predict future psychosis in early Parkinson disease. Neurology.

- Auld, D. S., Kornecook, T. J., Bastianetto, S., & Quirion, R. (2002). Alzheimer’s disease and the basal forebrain cholinergic system: relations to β-amyloid peptides, cognition, and treatment strategies. Progress in Neurobiology.

- Grothe, M., Heinsen, H., & Teipel, S. J. (2012). Atrophy of the Cholinergic Basal Forebrain Over the Adult Age Range and in Early Stages of Alzheimer's Disease. Biological Psychiatry, 71(9), 760-761.

- Weiner, M. W., Veitch, D. P., Aisen, P. S., Beckett, L. A., Cairns, N. J., Green, R. C., ... & Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging Initiative. (2017). The Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging Initiative 3: Continued innovation for clinical trial improvement. Alzheimer's & Dementia, 13(5), 561-571.

- Gunter, J., Thostenson, K., Borowski, B., Reid, R., Arani, A., Bernstein, M., ... & Jack Jr, C. (2017). ADNI-3 MRI Protocol. Alzheimer’s Dementia, 13(7), P104-P105.

- Tustison, N. J., Avants, B. B., Cook, P. A., Zheng, Y., Egan, A., Yushkevich, P. A., & Gee, J. C. (2010). N4ITK: improved N3 bias correction. IEEE transactions on medical imaging, 29(6), 1310-1320.

- Avants, B. B., Tustison, N., & Song, G. (2009). Advanced normalization tools (ANTS). Insight j, 2(365), 1-35.

- Ashburner, J., Barnes, G., Chen, C. C., Daunizeau, J., Flandin, G., Friston, K., ... & Penny, W. (2014). SPM12 manual. Wellcome Trust Centre for Neuroimaging, London, UK, 2464, 4.

- Lorio, S., Fresard, S., Adaszewski, S., Kherif, F., Chowdhury, R., Frackowiak, R. S., ... & Draganski, B. (2016). New tissue priors for improved automated classification of subcortical brain structures on MRI. Neuroimage, 130, 157-166.

Figures

Illustration of the location of CH4 (A, red) and CH123 (B, blue) on a template brain in stereotaxic space. The position of both regions in 3D space is displayed from a sagittal (C) and superior (D) view. The probabilistic maps from Lorio et al., are illustrated using the color scales at the bottom, showing which voxels were weighed more in calculating the density measurements.

Displaying the p-values for baseline differences between density and diagnosis group at baseline. CH4 (A) and CH123 (B) had significant differences in density between all but one of the groups (CH4 between CN and MCI).

Boxplot displaying baseline differences in CH4 density (A) and CH123 density (B) as assessed by voxel-based morphometry across CN, SMC, MCI, and AD groups. Significant differences were observed between density and diagnostic groups, with density decreasing with disease severity and subjects with an AD diagnosis having a significantly lower CH4 and CH123 density compared to all other groups.

Boxplot displaying differences in cholinergic basal forebrain nuclei 4 density based on diagnosis at follow-up visits. The subjects are grouped based on their baseline diagnosis and then sub-grouped based on their diagnosis at subsequent visits. CN subjects that progressed to MCI had significantly lower densities compared to subjects that remained CN. Subjects within the MCI diagnosis that progressed to AD had significantly lower densities than those that remained as MCI.

Boxplot displaying differences in cholinergic basal forebrain nuclei 1, 2, and 3 densities based on diagnosis at follow-up visits. The subjects are grouped based on their baseline diagnosis and then sub-grouped based on their diagnosis at subsequent visits. CN subjects that progressed to MCI had significantly lower densities compared to subjects that remained CN. Subjects within the MCI diagnosis that progressed to AD had significantly lower densities than those that remained as MCI.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.58530/2023/3045