3043

1H-MRSI of cortical and subcortical gray matter in cognitively unimpaired elderly: Associations with APOE4, CSF p-tau181 and MR morphometry

Anna Marie Chen1, Martin Gajdošík1, Rosemary Peralta1, Dishari Azad2, Helena Zheng1, Mia Gajdošík1, Ajax George1, Sinyeob Ahn3, Mickael Tordjman1,4, Julia Zabludovsky1, Yuxin Zhang5, LianLian Chen5, Henry Rusinek1,2, Guillaume Madelin1, Ricardo Osorio2, and Ivan Kirov1,6,7

1Center for Biomedical Imaging, Department of Radiology, New York University Grossman School of Medicine, New York, NY, United States, 2Department of Psychiatry, New York University Grossman School of Medicine, New York, NY, United States, 3Siemens Medical Solutions USA Inc., Malvern, PA, United States, 4Department of Radiology, Cochin Hospital, Paris, France, 5Department of Biostatistics, New York University School of Global Public Health, New York, NY, United States, 6Department of Neurology, New York University Grossman School of Medicine, New York, NY, United States, 7Center for Advanced Imaging Innovation and Research, Department of Radiology, New York University Grossman School of Medicine, New York, NY, United States

1Center for Biomedical Imaging, Department of Radiology, New York University Grossman School of Medicine, New York, NY, United States, 2Department of Psychiatry, New York University Grossman School of Medicine, New York, NY, United States, 3Siemens Medical Solutions USA Inc., Malvern, PA, United States, 4Department of Radiology, Cochin Hospital, Paris, France, 5Department of Biostatistics, New York University School of Global Public Health, New York, NY, United States, 6Department of Neurology, New York University Grossman School of Medicine, New York, NY, United States, 7Center for Advanced Imaging Innovation and Research, Department of Radiology, New York University Grossman School of Medicine, New York, NY, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Alzheimer's Disease, Gray Matter

1H-MRSI can examine spatiotemporal characteristics of metabolic dysfunction in multiple brain regions in early Alzheimer’s disease (AD) pathology. Since both cortical and subcortical gray matter structures have shown vulnerability to AD neurodegeneration, we tested whether regional gray matter metabolic abnormalities were associated with (i) APOE4 genotype, a risk factor for amyloid burden, (ii) CSF p-tau181, an indicator of tau burden, and (iii) morphometry metrics (volume, cortical thickness) indicative of neurodegeneration, in cognitively unimpaired elderly. We found lower caudate Cho and lower posterior cingulate Glx in APOE4 carriers compared to non-carriers. There were no metabolite relationships with CSF p-tau181 or morphometry.Introduction

Ex vivo histopathological1 and in vivo imaging2 studies have provided evidence for the distinct spatiotemporal progression of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) pathological hallmarks: amyloid aggregation, tau deposition, and cortical atrophy. However, whether regional metabolic changes are related to disease pathogenesis and associated with the presence of amyloid, tau, and/or regional neurodegeneration, is still not well-understood. There are only four previous proton (1H) MR spectroscopy (MRS) studies in cognitively unimpaired subjects3-6, and all used a single-voxel approach targeting the posterior cingulate. Therefore, we used 1H MR spectroscopic imaging (MRSI) in a similar population to evaluate changes in the levels of choline (Cho), creatine (Cr), glutamate plus glutamine (Glx), myo-inositol (mI), and N-acetylaspartate (NAA) from seven AD-vulnerable gray matter (GM) regions plus one control region (lateral occipital). We hypothesized findings confined to the posterior cingulate: reduced NAA with higher CSF p-tau1813, a marker of hyperphosphorylated tau; reduced NAA with lower cortical thickness, a measure of atrophy; and elevated mI in individuals who are at an increased risk of developing AD6 (apolipoprotein E4 carriers, APOE4+ vs. non-carriers, APOE4-). For metabolites in the lateral occipital, we hypothesized no correlations with CSF p-tau181, no correlations with cortical thickness, and no group differences between APOE4+ and APOE4-.Materials and Methods

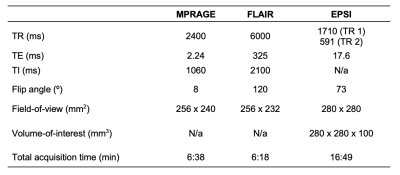

34 cognitively unimpaired older adults (22 female, 69±9 years old) were scanned at 3T (MAGNETOM Prisma, Siemens Healthcare, Erlangen, Germany) with a 20-channel transmit-receive head coil. The protocol included MPRAGE for anatomical localization, FLAIR for radiological assessment, and a prototype 3D EPSI sequence for 1H-MRSI7 (Table 1). Each subject’s MPRAGE was processed through FreeSurfer v6.0.0’s automatic segmentation pipeline to generate masks of bilateral subcortical (caudate, globus pallidus, putamen, thalamus) and cortical (posterior and isthmus cingulate, precuneus, lateral occipital) structures (Figure 1), as well as their volumetric or cortical thickness measures, respectively. Each subject’s subcortical volumes were normalized by their estimated total intracranial volume, to correct for variations in head size8,9. Spectral processing and analysis were performed using regional spectral integration on MIDAS10. Relative metabolite levels (institutional units, i.u.) were calculated using the internal water signal.The average time between the imaging exam and lumbar puncture was 29±23 months.

APOE4+ were defined as having at least one E4 allele. APOE4- were defined as having no E4 allele.

Age-adjusted Pearson’s correlations were used to examine associations between regional metabolite levels and CSF p-tau181, and volume or cortical thickness. A one-way ANCOVA, accounting for age, was used to assess regional metabolite level differences between APOE4+ vs. APOE4-. Statistical significance was defined as p<0.05.

Results

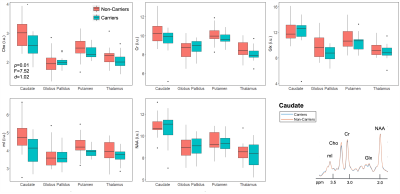

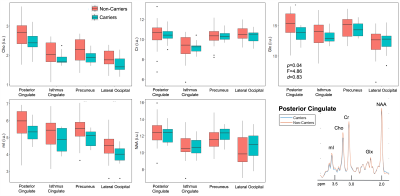

Population demographics and clinical characteristics are compiled in Table 2. We observed lower caudate Cho (p=0.01) (Figure 2) and lower posterior cingulate Glx (p=0.04) (Figure 3) in APOE4+ compared to APOE4-. We observed no correlation between metabolite levels in any region and CSF p-tau181; between subcortical metabolite levels and subcortical volumes; nor between cortical metabolite levels and cortical thicknesses. We also observed no group differences between APOE4+ and APOE4-, nor any correlations with CSF p-tau181 or cortical thickness, for any metabolite measured from the lateral occipital cortex.Discussion

APOE4 carriership mediated Cho and Glx differences in the caudate and posterior cingulate, respectively. As hypothesized, no findings were observed in the lateral occipital control region.Based on the previous studies3-6, we expected to find elevated posterior cingulate mI in APOE4+ vs. APOE4-. Instead, our finding of lower posterior cingulate Glx in APOE4+ vs. APOE- is similar to reports of lower posterior cingulate Glx/Cr11 and lower hippocampal glutamate-to-Cr ratios12 in AD patients vs. normal elderly. Given FDG-PET evidence of hypometabolism in AD, and the link between glucose and glutamate in the tricarboxylic cycle, reductions in Glx may suggest degeneration of glutamatergic neurons: decreased glucose results in impaired energy metabolism, and decreased glutamate and glutamine synthesis13,14.

Additionally, we found lower caudate Cho in APOE4+ vs. APOE4-. This was an unexpected result, as studies have generally observed elevated Cho/Cr ratio in AD patients, if at all15. There is evidence for amyloid accumulation within the cortico-striato-thalamic network, specifically the putamen, caudate, and amygdala16, and this pathology may lead to dysregulated Cho metabolism. Reductions in Cho, a marker of membrane synthesis and degradation, has been linked to unfolded protein pro-death signaling response in cancers17, and a similar mechanism may be initiated in response to the misfolding of extracellular amyloid protein in asymptomatic cases. However, we did not find an accompanying reduction in caudate NAA, a marker of neuronal dysfunction. Acute reductions of Cho in early AD may initiate compensatory upregulation of pro-survival pathways over time, but more research is needed to elucidate the implications of Cho changes in cognitively unimpaired subjects.

Our study combining quantitative 1H-MRSI with an atlas-based region-of-interest selection allowed us to: minimize white matter partial volume effects seen in single-voxel 1H-MRS studies of GM18; measure metabolite levels of multiple GM regions, including many not previously studied in cognitively unimpaired individuals; and avoid using metabolite ratios, which cannot differentiate between changes in the numerator vs. denominator. Lastly, the use of established genetic, CSF, and MRI biomarkers allowed us to interpret the 1H-MRSI results in accordance with the AT(N) research framework19 in terms of tau (T, CSF p-tau181) and neurodegeneration [(N), MRI atrophy].

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a pilot grant to Dr. Kirov (P30AG008051) from the Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center (P30AG066512) at New York University Langone Health.References

1 Braak, H. & Braak, E. Neuropathological stageing of Alzheimer-related changes. Acta Neuropathologica 82, 239-259 (1991).https://doi.org:10.1007/BF003088092 Chandra, A. et al. Applications of amyloid, tau, and neuroinflammation PET imaging to Alzheimer's disease and mild cognitive impairment. Hum Brain Mapp 40, 5424-5442 (2019).https://doi.org:10.1002/hbm.24782

3 Kara, F. et al. 1H MR spectroscopy biomarkers of neuronal and synaptic function are associated with tau deposition in cognitively unimpaired older adults. Neurobiol Aging 112, 16-26 (2022).

4 Kantarci, K. et al. Magnetic resonance spectroscopy, β-amyloid load, and cognition in a population-based sample of cognitively normal older adults. Neurology 77, 951-958 (2011).

5 Nedelska, Z. et al. <sup>1</sup>H-MRS metabolites and rate of β-amyloid accumulation on serial PET in clinically normal adults. Neurology 89, 1391-1399 (2017).https://doi.org:10.1212/wnl.0000000000004421

6 Voevodskaya, O. et al. Myo-inositol changes precede amyloid pathology and relate to APOE genotype in Alzheimer disease. Neurology 86, 1754-1761 (2016).

7 Ding, X. Q. et al. Reproducibility and reliability of short-TE whole-brain MR spectroscopic imaging of human brain at 3T. Magn Reson Med 73, 921-928 (2015).https://doi.org:10.1002/mrm.25208

8 Voevodskaya, O. et al. The effects of intracranial volume adjustment approaches on multiple regional MRI volumes in healthy aging and Alzheimer's disease. Front Aging Neurosci 6, 264 (2014).https://doi.org:10.3389/fnagi.2014.00264

9 Sämann, P. G. et al. FreeSurfer-based segmentation of hippocampal subfields: A review of methods and applications, with a novel quality control procedure for ENIGMA studies and other collaborative efforts. Hum Brain Mapp 43, 207-233 (2022).https://doi.org:10.1002/hbm.25326

10 Maudsley, A. A. et al. Comprehensive processing, display and analysis for in vivo MR spectroscopic imaging. NMR Biomed 19, 492-503 (2006).https://doi.org:10.1002/nbm.1025

11 Su, L. et al. Whole-brain patterns of (1)H-magnetic resonance spectroscopy imaging in Alzheimer's disease and dementia with Lewy bodies. Transl Psychiatry 6, e877 (2016).https://doi.org:10.1038/tp.2016.140

12 Rupsingh, R., Borrie, M., Smith, M., Wells, J. L. & Bartha, R. Reduced hippocampal glutamate in Alzheimer disease. Neurobiol Aging 32, 802-810 (2011).https://doi.org:10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2009.05.002

13 Revett, T. J., Baker, G. B., Jhamandas, J. & Kar, S. Glutamate system, amyloid ss peptides and tau protein: functional interrelationships and relevance to Alzheimer disease pathology. J Psychiatry Neurosci 38, 6-23 (2013).https://doi.org:10.1503/jpn.110190

14 Bukke, V. N. et al. The Dual Role of Glutamatergic Neurotransmission in Alzheimer's Disease: From Pathophysiology to Pharmacotherapy. Int J Mol Sci 21 (2020).https://doi.org:10.3390/ijms21207452

15 Murray, M. E. et al. Early Alzheimer's disease neuropathology detected by proton MR spectroscopy. J Neurosci 34, 16247-16255 (2014).https://doi.org:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2027-14.2014

16 Cho, S. H. et al. Amyloid involvement in subcortical regions predicts cognitive decline. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 45, 2368-2376 (2018).https://doi.org:10.1007/s00259-018-4081-5

17 Iorio, E. et al. A novel roadmap connecting the (1)H-MRS total choline resonance to all hallmarks of cancer following targeted therapy. Eur Radiol Exp 5, 5 (2021).https://doi.org:10.1186/s41747-020-00192-z

18 Tal, A., Kirov, II, Grossman, R. I. & Gonen, O. The role of gray and white matter segmentation in quantitative proton MR spectroscopic imaging. NMR Biomed 25, 1392-1400 (2012).https://doi.org:10.1002/nbm.2812

19 Jack, C. R., Jr. et al. NIA-AA Research Framework: Toward a biological definition of Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimer's & dementia : the journal of the Alzheimer's Association 14, 535-562 (2018).https://doi.org:10.1016/j.jalz.2018.02.018

Figures

Table 1. Imaging protocol.

Table 2. Participant characteristics. Data are expressed as mean (and standard deviation) or number of participants (and percentage), as appropriate.

Figure 1. Subcortical and cortical gray matter regions of interest, obtained from FreeSurfer’s automated segmentation pipeline, overlaid on coronal, sagittal, and axial MPRAGE slices from a single subject (top). For each subcortical (left column) and cortical (right column) gray matter region, individual spectra from all 34 subjects are overlaid on the same frequency and intensity scales (bottom).

Figure 2. Group differences in subcortical gray matter. Boxplots show subcortical metabolite distributions within APOE4 carriers (n=12) and non-carriers (n=22). Using a one-way ANCOVA, we observed lower Cho in the caudate of carriers vs. non-carriers, with a large magnitude of effect (Cohen’s d > 0.8). Spectra from the caudate were averaged amongst carriers (blue) and non-carriers (orange), and overlaid on the same frequency and intensity scales (bottom right). Note, visually, the lower amplitude of the Cho peak for carriers compared to non-carriers.

Figure 3. Group differences in cortical gray matter. Boxplots show cortical metabolite distributions within APOE4 carriers (n=12) and non-carriers (n=22). Using a one-way ANCOVA, we observed lower Glx in the posterior cingulate of carriers vs. non-carriers, with a large magnitude of effect (Cohen’s d > 0.8). Spectra from the posterior cingulate were averaged amongst carriers (blue) and non-carriers (orange), and overlaid on the same frequency and intensity scales (bottom right). Although subtle, we note the lower amplitude of the Glx peak for carriers compared to non-carriers.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.58530/2023/3043