3030

Differences in cerebellar fiber tract dispersion in coronary artery disease patients are associated with episodic memory and processing speed1Physics, Concordia University, Montreal, QC, Canada, 2Centre ÉPIC and Research Center, Montreal Heart Institute, Montreal, QC, Canada, 3PERFORM Centre, Concordia University, Montreal, QC, Canada, 4Department of Biomedical Science, Université de Montreal, Montreal, QC, Canada, 5BrainLab, Hurvitz Brain Sciences Program, Sunnybrook Research Institute, Toronto, ON, Canada, 6Psychology, Concordia University, Montreal, QC, Canada, 7Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, Concordia University, Montreal, QC, Canada, 8Department of Medicine, Université de Montreal, Montreal, QC, Canada, 9Research Center, Institut Universitaire de Gériatrie de Montréal, Montreal, QC, Canada

Synopsis

Keywords: White Matter, Diffusion/other diffusion imaging techniques, DTI, NODDI

Here we characterized the impact of coronary artery disease (CAD) on the brain’s white matter (WM) using diffusion tensor (DTI) and neurite orientation dispersion and density imaging (NODDI). Mean diffusivity was higher in CAD patients in occipital WM and there were differences in orientation dispersion in several tracts between CAD patients and healthy controls. Alterations in fiber dispersion of cerebellar WM were associated with global cognition, episodic memory, and processing speed. Our study supports the use of advanced diffusion imaging models for the early detection of subtle WM damage in populations at risk of developing dementia such as CAD patients.Introduction

Coronary artery disease (CAD) patients are at an increased risk of developing cognitive decline and dementia 1,2. CAD and vascular risk factors impact several components of brain health, including cerebral vessels, grey matter volume and white matter (WM) integrity 3,4. WM hyperintensities (WMH), which have a high prevalence in CAD, likely contribute to the cognitive impairments seen in CAD patients 5,6. However, macrostructural measures of the brain do not suffice to fully explain the impact of CAD on cognition as shown in 1. This suggests that more sensitive neuroimaging metrics are needed to capture subtle changes in brain health. For instance, diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) has been used to measure alterations in so-called “normal-appearing” WM in CAD and changes to diffusion tensor (DTI) metrics were found in several WM regions that are important for cognition 7. While there is evidence for an association between CAD and WM changes 6-8, the mechanisms through which WM damage occurs and causes cognitive decline and neuropathology are poorly understood, as commonly used techniques are physiologically unspecific when used in isolation. We thus used neurite orientation dispersion and density imaging (NODDI) 9, along with DTI, to obtain greater insights into the pathophysiological mechanisms underlying WM microstructure changes in CAD patients, and related changes in WM microstructure to cognitive outcomes.Methods

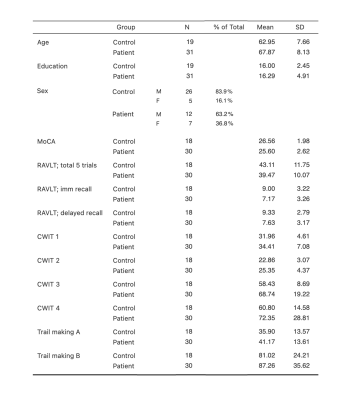

MRI data were acquired in 31 CAD patients and 19 healthy controls (HCs) that were 50 years old and above, without history of stroke, neurological or respiratory disorders, and without significant cognitive impairment (Mini-mental state examination ≥ 25) (Table 1). These participants also completed a comprehensive neuropsychological assessment: Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA; global cognition), Rey auditory verbal learning test (RAVLT; episodic memory), D-KEFS Color Word Interference Test (CWIT; processing speed and executive function), and Trail Making Test part A and B (executive function). Multi-shell DWI data (TE/TR= 106/6000 ms, b= 300, 700, 2500 s/mm2; 64 directions) were preprocessed and fitted to the DTI and NODDI models to obtain maps of fractional anisotropy (FA), mean diffusivity (MD), orientation dispersion (OD) and intracellular volume fraction (ICVF). Voxel-wise group comparisons of WM microstructure were conducted using two-sample t-tests in SPM, with sex and age as covariates, for each of these WM metrics. Regions of interest (ROIs) were then defined based on statistically significant clusters in voxel-wise analyses (pFDR < 0.05). Associations with cognitive performance were investigated by conducting correlation analyses (Pearson’s) between mean values of WM microstructure metrics within the ROIs and scores on cognitive tasks in the whole sample (see cognitive outcomes in Table 1).Results

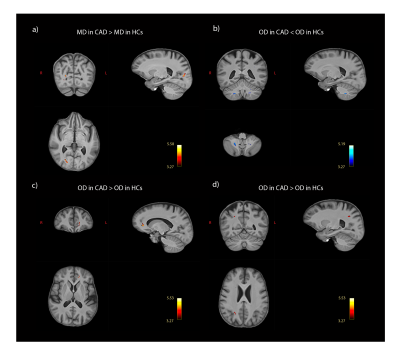

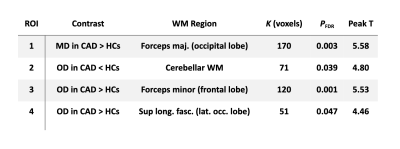

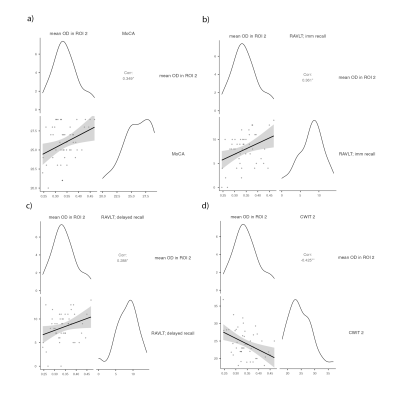

MD was higher in CAD patients than in HCs in a WM region that is part of the forceps major in the occipital lobe (pFDR = 0.003; Fig 1A). OD was lower in patients in the cerebellar WM tracts (pFDR = 0.039; Fig 1B) and higher in two clusters: one in the forceps minor in the frontal lobe (pFDR = 0.001; Fig 1C) and one in the superior longitudinal fasciculus, near the lateral occipital lobe (pFDR = 0.047; Fig 1D). There were no significant group differences in FA and ICVF. Four ROIs were formed based on clusters where significant between-group differences were found (see Fig 1 and Table 2). Significant correlations were identified between mean OD in the cerebellar WM ROI and scores on the MoCA (r = 0.349, p= 0.015), immediate (r = 0.361, p= 0.012) and delayed recall (r = 0.288, p= 0.048) of the RAVLT, and execution time on the reading condition of the CWIT (r = -0.425, p= 0.003), where lower OD was associated with poorer performance (Fig 2). There was no significant correlation between other ROIs and cognitive outcomes (p > 0.05).Discussion

WM microstructure differences between HCs and CAD patients were found in several different brain regions (frontal, occipital, and cerebellar WM tracts), indicating a widespread effect of CAD on the brain, even in this incomplete sample. These differences remained significant after adjusting for covariates, which suggests they likely represent alterations to WM due to the disease status and not to sex or age differences between groups. Our findings indicate that alterations to WM microstructure in CAD patients would consist in a reorganization of fiber tracts (i.e., increased/decreased orientation dispersion), while axonal content seems to be preserved. The significant associations identified between cerebellar WM and scores in various cognitive domains (i.e., global cognition, episodic memory, and processing speed) are in line with the now well-known role of the cerebellum in a wide range of cognitive processes and its involvement in cognitive impairment 10-12.Conclusion

WM microstructural health was altered in CAD patients without significant cognitive impairment compared to healthy controls. We showed the pertinence of combining DTI and NODDI as it allows for more specific inferences regarding underlying biological mechanisms. Namely, we found that fiber tract dispersion was the component that differed most between groups and that OD in cerebellar WM was associated with performance in various cognitive domains. In future work, we will assess grey matter and WMH volume in the full sample to evaluate the relative timing of alterations of each of these components of brain health in CAD and their associations to cognition.Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the contribution of Paule Samson, MR technologist, of Julie Lalongé, research assistant and medical electrophysiology technologist, and of all the staff of the EPIC center that has contributed to this project. We also want to thank all students and research assistants who have helped with data acquisitions: Roni Zaks, Robert Hovey, Stephanie Beram, Alexandre bailey, Agathe Godet and Kathia Saillant, as well as the research participants who took part in this study.

SAT was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR: FBD 175862).

CJG was supported by the Heart and Stroke Foundation New Investigator Award and J.M. Barnett fellowship, the Michal and Renata Hornstein Chair in Cardiovascular Imaging, and the Heart and Stroke Foundation Grant-inAid G-17-0018336.

LB was supported by Mirella and Lino Saputo Research Chair in Cardiovascular Health and the Prevention of Cognitive Decline from the Universite de Montreal at the Montreal Heart Institute.

References

- Zheng, L., Mack, W. J., Chui, H. C., Heflin, L., Mungas, D., Reed, B., DeCarli, C., Weiner, M. W., & Kramer, J. H. (2012). Coronary Artery Disease Is Associated with Cognitive Decline Independent of Changes on Magnetic Resonance Imaging in Cognitively Normal Elderly Adults. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 60(3), 499–504. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03839.x

- Polidori, M. C., Pientka, L., & Mecocci, P. (2012). A Review of the Major Vascular Risk Factors Related to Alzheimer’s Disease. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease, 32(3), 521–530. https://doi.org/10.3233/JAD-2012-120871

- Barekatain, M., Askarpour, H., Zahedian, F., Walterfang, M., Velakoulis, D., Maracy, M. R., & Jazi, M. H. (2014). The relationship between regional brain volumes and the extent of coronary artery disease in mild cognitive impairment. Journal of Research in Medical Sciences : The Official Journal of Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, 19(8), 739–745.

- Launer, L. J., Lewis, C. E., Schreiner, P. J., Sidney, S., Battapady, H., Jacobs, D. R., Lim, K. O., D’Esposito, M., Zhang, Q., Reis, J., Davatzikos, C., & Bryan, R. N. (2015). Vascular Factors and Multiple Measures of Early Brain Health: CARDIA Brain MRI Study. PLOS ONE, 10(3), e0122138. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0122138

- O’Brien, J. T. (2014). Clinical Significance of White Matter Changes. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 22(2), 133–137. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jagp.2013.07.006

- Johansen, M. C., Gottesman, R. F., Kral, B. G., Vaidya, D., Yanek, L. R., Becker, L. C., Becker, D. M., & Nyquist, P. (2021). Association of Coronary Artery Atherosclerosis With Brain White Matter Hyperintensity. Stroke, 52(8), 2594–2600. https://doi.org/10.1161/STROKEAHA.120.032674

- Poirier, S. E., Suskin, N., Lawrence, K. S. S., Shoemaker, J. K., & Anazodo, U. C. (2021). Cardiac disease may exacerbate age-related white matter disruptions: improvements are feasible after cardiac rehabilitation.

- Santiago, C., Herrmann, N., Swardfager, W., Saleem, M., Oh, P. I., Black, S. E., & Lanctôt, K. L. (2015). White Matter Microstructural Integrity Is Associated with Executive Function and Processing Speed in Older Adults with Coronary Artery Disease. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 23(7), 754–763. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jagp.2014.09.008

- Zhang, H., Schneider, T., Wheeler-Kingshott, C. A., & Alexander, D. C. (2012). NODDI: Practical in vivo neurite orientation dispersion and density imaging of the human brain. NeuroImage, 61(4), 1000–1016. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.03.072

- Koziol, L. F., Budding, D., Andreasen, N., D’Arrigo, S., Bulgheroni, S., Imamizu, H., Ito, M., Manto, M., Marvel, C., Parker, K., Pezzulo, G., Ramnani, N., Riva, D., Schmahmann, J., Vandervert, L., & Yamazaki, T. (2014). Consensus Paper: The Cerebellum’s Role in Movement and Cognition. Cerebellum (London, England), 13(1), 151–177. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12311-013-0511-x

- Chen, Y., Landin-Romero, R., Kumfor, F., Irish, M., Hodges, J. R., & Piguet, O. (2020). Cerebellar structural connectivity and contributions to cognition in frontotemporal dementias. Cortex, 129, 57–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cortex.2020.04.013

- Lin, C.-Y., Chen, C.-H., Tom, S. E., Kuo, S.-H., & for the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative. (2020). Cerebellar Volume Is Associated with Cognitive Decline in Mild Cognitive Impairment: Results from ADNI. The Cerebellum, 19(2), 217–225. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12311-019-01099-1

Figures