3029

A test-retest analysis for ventral intermediate nucleus localization with CSD tractography for deep brain stimulation.1Radiology, University Hospitals Leuven, Leuven, Belgium, 2Imaging and Pathology, KU Leuven, Leuven, Belgium, 3Neurosciences, KU Leuven, Leuven, Belgium, 4Neurology, University Hospitals Leuven, Leuven, Belgium, 5Neurosurgery, University Hospitals Leuven, Leuven, Belgium

Synopsis

Keywords: White Matter, Diffusion Tensor Imaging, Deep brain stimulation

We found that the location of the ventral intermediate nucleus (Vim) as determined with dMRI tractography differed only 0.92 mm on average on subsequent scans within the same individual (SD: 0.51 mm) in a test-retest study of 29 healthy individuals. The difference with a commonly used manual method that locates the Vim at fixed distances in relation to the commissures and third ventricular wall was more pronounced: on average 2.44 mm (SD: 0.92 mm). We believe that dMRI tractography based DBS target determination seems feasible and rather accurate, given that acquisition parameters and post-processing are optimal.Introduction

Deep brain stimulation (DBS) is routinely performed in pharmacorefractory essential tremor (ET) patients [1], [2]. Classically, the ventral intermediate nucleus (Vim) is targeted [2]. Given the lack of distinct borders between the thalamic subnuclei on routine imaging, targeting is usually based on closeby anatomical landmarks, including the anterior and posterior commissures and the wall of the third ventricle. [3]. Despite optimization through intraoperative recordings and stimulation, such a targeting method is limited in taking into account individual anatomic variability and may lead to suboptimal targeting of the Vim, which in turn may lead to reduced clinical effectiveness and more side effects [2].In recent years, tractography by means of diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) or constrained spherical deconvolution (CSD) has emerged as an alternative for targeting of the Vim [4], where the target can be defined as the intersection of the horizontal bicommissural plane with the dentato-rubro-thalamic tract (DRTT) [5]–[7].

For implementation in clinical practice, it is important that the tractography is performed in a precise and reproducible manner, which strongly depends on the applied method. We investigated the performance of a probabilistic CSD-based tractography method in pinpointing the location of the Vim and compared this to the performance of a conventional indirect targeting approach in 29 healthy individuals that were scanned three times at the different time points.

Material and Methods

Twenty-nine healthy subjects (mean age=48.4y, SD=8.7) were included. The study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki with approval by the institutional ethical committee. The subjects received oral and written information and provided oral and written consent. Data from 1 subject was excluded due to an image artefact.Imaging was performed on a 3T Philips Achieva D-Stream scanner with a 32-channel receive only head coil and gradient strength of 80mT/m and slew rate of 100 mT/s/m. Imaging included a 3D T1-weighted (3D-TFE, TR=5.896 ms, TE=2.552 ms, flip angle=8, isotropic acquisition voxel size=0.8 mm) image and multishell diffusion-weighted image series (11 b0, 20 b200, 20 b500, 30 b1200, 61 b2400 and 61 b4000, TE=85 ms, TR=6400 ms, WFS=27.202 pixels, total readout time=0.0618 s, acquisition voxel size=1.96x1.96x2 mm, sense-factor=1.4, multiband-factor=3, total acquisition time 21 minutes) and reversed-phase encoded diffusion-weighted acquisition.

Imaging was repeated three times with identical acquisition parameters: at baseline (t1), 3 months later (t2), and 1 year after baseline(t3).

dMRI data processing was performed with MRtrix3 v3.0.3 [8] and included denoising, Gibbs ringing correction, topup, eddy, upsampling to 1.3 mm isotropic resolution, and spherical deconvolution response estimation. Probabilistic tractography with iFod2 [9] of the left and right DRTT was done in an automated fashion described in detail in [9] for each timepoint registered to the mean T1w image of the three imaging sessions.

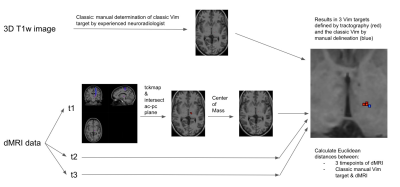

Determination of the left and right voxel positions (x,y,z) of the classic target for DBS implantation in the Vim was performed by an experienced neuroradiologist. For this a commonly used method was applied that locates the somatotopic hand region within the Vim 15 mm lateral to the midcommissural point (or 10.5 mm lateral from the wall of the third ventricle), 25% of the anterior commissure-posterior commissure (AC–PC) distance anterior to the posterior commissure, and at the level of the horizontal commissural plane [3].

To reveal the dMRI derived Vim position the following was done: a) the streamlines of the DRTT of each time point were converted to an image map using MRtrix3 tckmap; b) an intersection between the tract maps and the ac-pc plane was calculated and the centre of mass was determined using NiBabel [10]. See figure 1.

We then calculated the Euclidean distances between dMRI derived Vim positions of timepoints t1 and t2, t2 and t3 and t1 and t3. Finally Euclidean distances were calculated between the classically determined Vim and the mean of the 3 dMRI derived Vim positions.

Results and Discussion

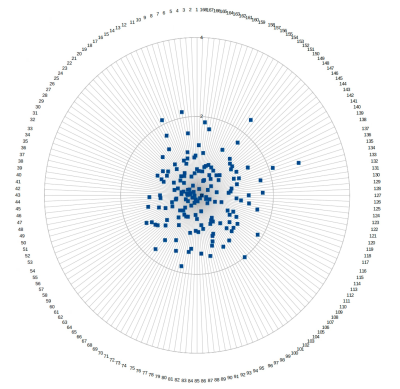

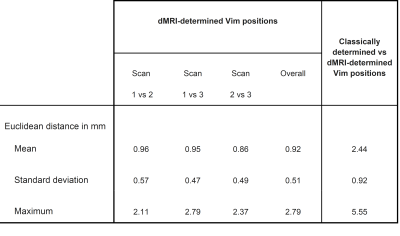

Table 1 shows the Euclidean distances between a) the three repetitions of the diffusion mri determined Vim positions (i.e the centre of mass of the DRTT tract at the ac-pc plane) and b) the classically manually determined position and the mean of the 3 diffusion determined positions. Figure 2 shows the Euclidean distances of the 168 observations (28 subjects x 2 sides x 3 timepoints) of the diffusion MRI determined Vim positions.For the dMRI determined position of the Vim the mean Euclidean distance between all three timepoints of imaging was 0.92 mm, with a standard deviation of 0.51 mm. The maximum Euclidean distance was 2.79 mm.

When comparing the mean of the dMRI determined Vim position with the classically determined position, the mean Euclidean distance was 2.44 mm, with a standard deviation of 0.92 mm. The maximum Euclidean distance was 5.55 mm.

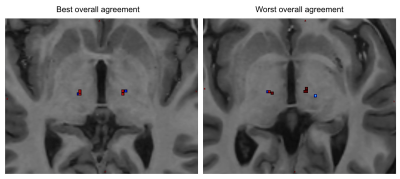

Figure 3 shows examples of the location of the 3 dMRI determined Vim positions and the location of the classically determined Vim position. We show the 2 subjects with best and worst overall agreement.

Determination of the Vim by CSD iFOD2 tractography seems highly repeatable. Further study is needed to assess the accuracy by evaluating clinical therapeutic outcome in patients.

Acknowledgements

No acknowledgement found.References

[1] C. Iorio-Morin, A. Fomenko, and S. K. Kalia, “Deep-Brain Stimulation for Essential Tremor and Other Tremor Syndromes: A Narrative Review of Current Targets and Clinical Outcomes,” Brain Sci., vol. 10, no. 12, p. 925, Dec. 2020, doi: 10.3390/brainsci10120925.

[2] V. T. Lehman et al., “MRI and tractography techniques to localize the ventral intermediate nucleus and dentatorubrothalamic tract for deep brain stimulation and MR-guided focused ultrasound: a narrative review and update,” Neurosurg. Focus, vol. 49, no. 1, p. E8, Jul. 2020, doi: 10.3171/2020.4.FOCUS20170.

[3] T. Chen, Z. Mirzadeh, K. Chapple, M. Lambert, R. Dhall, and F. A. Ponce, “‘Asleep’ deep brain stimulation for essential tremor,” J. Neurosurg., vol. 124, no. 6, pp. 1842–1849, Jun. 2016, doi: 10.3171/2015.6.JNS15526.

[4] O. Parras, P. Domínguez, A. Tomás-Biosca, and J. Guridi, “The role of tractography in the localisation of the Vim nucleus of the thalamus and the dentatorubrothalamic tract for the treatment of tremor,” Neurol. Engl. Ed., vol. 37, no. 8, pp. 691–699, Oct. 2022, doi: 10.1016/j.nrleng.2019.09.008.

[5] A. I. Yang et al., “Tractography-Based Surgical Targeting for Thalamic Deep Brain Stimulation: A Comparison of Probabilistic vs Deterministic Fiber Tracking of the Dentato-Rubro-Thalamic Tract,” Neurosurgery, vol. 90, no. 4, pp. 419–425, Apr. 2022, doi: 10.1227/NEU.0000000000001840.

[6] V. A. Coenen, B. Mädler, H. Schiffbauer, H. Urbach, and N. Allert, “Individual Fiber Anatomy of the Subthalamic Region Revealed With Diffusion Tensor Imaging: A Concept to Identify the Deep Brain Stimulation Target for Tremor Suppression,” Neurosurgery, vol. 68, no. 4, pp. 1069–1076, Apr. 2011, doi: 10.1227/NEU.0b013e31820a1a20.

[7] K. Yamada et al., “MR Imaging of Ventral Thalamic Nuclei,” Am. J. Neuroradiol., vol. 31, no. 4, pp. 732–735, Apr. 2010, doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A1870.

[8] J.-D. Tournier et al., “MRtrix3: A fast, flexible and open software framework for medical image processing and visualisation,” NeuroImage, vol. 202, p. 116137, Nov. 2019, doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2019.116137.

[9] A. M. Radwan et al., “An atlas of white matter anatomy, its variability, and reproducibility based on constrained spherical deconvolution of diffusion MRI,” NeuroImage, vol. 254, p. 119029, Jul. 2022, doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2022.119029.

[10] M. Brett et al., “nipy/nibabel: 3.2.2.” Zenodo, Jun. 06, 2022. doi: 10.5281/zenodo.6617121.

Figures