3027

Sex-specific differences of the number of fiber orientations (NuFO) in the human brain1UMC Utrecht, Utrecht, Netherlands

Synopsis

Keywords: White Matter, Brain, crossing fibers, biomarker, NuFO, FA

Diffusion MRI-based biomarkers are commonly used to assess brain microstructural properties. Mathematical models have been developed to calculate various metrics; each are sensitive to different tissue features. Here, we investigate whether there are differences in the number of fiber orientations (NuFO) between male and female brains and how these results compare to corresponding DTI-derived fractional anisotropy (FA) findings. Results show NuFO-based differences with high effect size (>1 Cohen’s D) in hippocampi, which are undetected in FA-tests. Therefore, NuFO could provide complementary aspects to DTI metrics to capture differences in microstructural organization.Introduction

Diffusion MRI is among the most popular techniques to investigate brain microstructure. Most clinical applications are based on the diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) model. DTI metrics have been repeatedly shown as sensitive biomarkers of brain tissue microstructure[1,2].However, in voxels containing multiple fiber orientations, changes in DTI metrics, e.g. fractional anisotropy (FA), are not specific, and can originate from changes in any of the underlying tissue fibers. This conceptual limitation affects a large part of the brain, as multi-fiber configurations are present in the vast majority of the brain white matter[3,4]. More recently, methods investigating fiber orientation distributions (FOD) obtained from spherical deconvolution are becoming an increasingly popular solution to obtain microstructural metrics that overcome the limitations of DTI. In this work, we evaluate whether the number of fiber orientations (NuFO) can provide complementary insights into tissue microstructure when compared to conventional FA-based results. As an example study, we opted to evaluate potential differences between female and male brain microstructure, as such group differences are already established in the literature serving as a reference[5,6].Methods

Minimally processed dMRI data were collected from the Human Connectome Project (HCP)[7,8]. Briefly, a motion- and distortion corrected dataset consisted of 18 non-DWIs (b-value = 0 s/mm2) and 90 DWIs per shell with b-values equal to 1000/2000/3000 s/mm2, with a voxel size of 1.25mm isotropic and a sample size of 408(243 females) participants.The diffusion tensor was estimated with 9 non-DWIs and 90 DWIs at b=1000 s/mm2 using the weighted linear least squares[9] method.

NuFO[10] was calculated after estimating the FOD with the Generalized Richardson-Lucy (GRL)[11] spherical deconvolution framework. Corrections for gradient non-linearities were performed both in the DTI fit and the FOD estimation[12–14].

The signal contributions of white matter (WM), grey matter (GM) and cerebrospinal fluid were modelled separately. The WM signal was modelled using DTI. The tensor eigenvalues were derived for each subject by looking at voxels with FA>0.7. The main orientations of the FODs were derived with a gradient descent method and then NuFO was determined while discarding FOD peaks below 20% of maximum peak amplitude. The maximum NuFO was limited to 3.

For the group comparison, we used Permutation Analysis of Linear Models[15–19]. Significance was determined at pcorr<0.05 using family-wise error rate adjustment. Threshold-Free Cluster Enhancement[20] was used to amplify p-values. Total intracranial volumes (TIV) of the subjects were added as a nuisance regressor.

Results

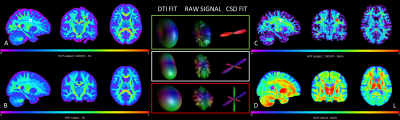

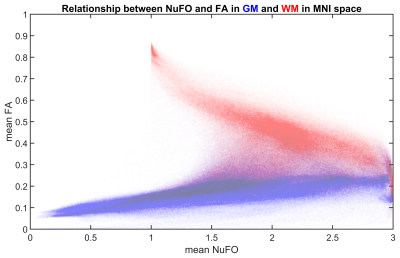

Fig. 1 shows an example subject from the HCP cohort and the population mean maps for NuFO and FA in MNI space. In WM, there is a reverse relationship between the two metrics, for example, in the corpus callosum, a high FA value has a NuFO value of 1. Therefore, this region has single fiber orientation as shown by the population maps. However, DTI estimation in areas with divergent fiber populations results in a lower FA. Deep GM nuclei like the thalamus or caudate also have ~3 NuFO and low FA.Fig. 2 shows a joint distribution histogram of voxel-wise NuFO and FA. High FA values (>0.8) only occur in WM and coincide with a NuFO value of 1. In other WM regions a higher NuFO corresponds to a lower FA. FA values in GM are generally low (~0.2) and in a narrow range, while NuFO assumes values between 1 and 3 at the same locations.

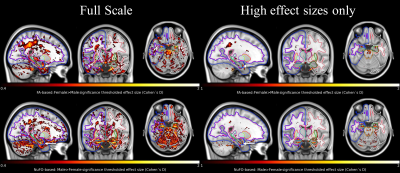

In Fig. 3, we examine voxel-wise differences in FA and NuFO between females and males. Both NuFO- and FA-based comparisons show widespread differences (left panel). Moreover, the NuFO-based analysis reveals differences in hippocampi with large effect sizes (Cohen’s D>1), whereas the effect sizes observed for FA are remarkably lower. Since there is a reverse relationship between NuFO and FA in WM, as shown in Fig. 2, we compared the effect sizes of ‘Male > Female’ NuFO-tests with ‘Female > Male’ FA-tests. Also, males do not show higher FA than females and females do not show higher NuFO than males, hence both are not shown.

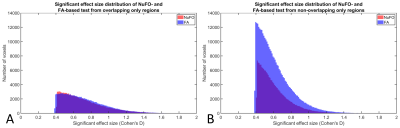

Fig. 4 shows the distribution of effect sizes in voxels where FA or NuFO were significantly different between males and females. The figure shows separate distributions for voxels in which both metrics were significantly different (in section A) or only one of the two (in section B). Fig 4/B shows that the largest amount of differences were observed for NuFO only (340 cm3 or 18.4% of the MNI brain volume), followed by FA only (188 cm3 or 10.2%), and both metrics (125 cm3 or 6.7%).

Discussion and Conclusion

We investigated sex-specific differences in the human brain with DTI-based FA and GRL-based NuFO biomarkers, while adjusting for TIV. NuFO-based comparisons showed considerably more differences between sexes than FA. Of the total significant areas, only 19% of the regions show differences with both metrics, while 52% was showed with NuFO only. NuFO-based tests show large amount of differences with high effect sizes in the hippocampi. Most previous research shows similar patterns of higher FA for females, but are limited to core WM areas[21,22]. NuFO was able to reveal complementary differences compared to FA-based tests when used to investigate sex-specific differences in the brain and may offer new insights into the structure of the brain.Acknowledgements

No acknowledgement found.References

[1] Baek SH, Park J, Kim YH, Seok HY, Oh KW, Kim HJ, et al. Usefulness of diffusion tensor imaging findings as biomarkers for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Sci Rep 2020;10:1–9. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-62049-0.

[2] Andica C, Kamagata K, Hatano T, Saito Y, Ogaki K, Hattori N, et al. MR Biomarkers of Degenerative Brain Disorders Derived From Diffusion Imaging. J Magn Reson Imaging 2020;52:1620–36. doi:10.1002/jmri.27019.

[3] David S, Mesri HY, Guo F, Leemans A, De Luca A. Diffusion MRI analyses of complex fiber configurations in white matter and the cortex. Int Soc Magn Reson Med 2020:7045.

[4] Jeurissen B, Leemans A, Tournier JD, Jones DK, Sijbers J. Investigating the prevalence of complex fiber configurations in white matter tissue with diffusion magnetic resonance imaging. Hum Brain Mapp 2013;34:2747–66. doi:10.1002/hbm.22099.

[5] Tyan YS, Liao JR, Shen CY, Lin YC, Weng JC. Gender differences in the structural connectome of the teenage brain revealed by generalized q-sampling MRI. NeuroImage Clin 2017;15:376–82. doi:10.1016/j.nicl.2017.05.014.

[6] Ingalhalikar M, Smith A, Parker D, Satterthwaite TD, Elliott MA, Ruparel K, et al. Sex differences in the structural connectome of the human brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci 2014;111:823–8. doi:10.1073/pnas.1316909110.

[7] Glasser MF, Sotiropoulos SN, Wilson JA, Coalson TS, Fischl B, Andersson JL, et al. The minimal preprocessing pipelines for the Human Connectome Project. Neuroimage 2013;80:105–24. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.04.127.

[8] Van Essen DC, Smith SM, Barch DM, Behrens TEJ, Yacoub E, Ugurbil K. The WU-Minn Human Connectome Project: An overview. Neuroimage 2013;80:62–79. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.05.041.

[9] Veraart J, Sijbers J, Sunaert S, Leemans A, Jeurissen B. Weighted linear least squares estimation of diffusion MRI parameters: Strengths, limitations, and pitfalls. Neuroimage 2013;81:335–46. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.05.028.

[10] Dell’Acqua F, Simmons A, Williams SCRR, Catani M. Can spherical deconvolution provide more information than fiber orientations? Hindrance modulated orientational anisotropy, a true-tract specific index to characterize white matter diffusion. Hum Brain Mapp 2013;34:2464–83. doi:10.1002/hbm.22080.

[11] Guo F, Leemans A, Viergever MA, Dell’Acqua F, De Luca A. Generalized Richardson-Lucy (GRL) for analyzing multi-shell diffusion MRI data. Neuroimage 2020;218:116948. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2020.116948. [12] Sotiropoulos SN, Jbabdi S, Xu J, Andersson JL, Moeller S, Auerbach EJ, et al. Advances in diffusion MRI acquisition and processing in the Human Connectome Project. Neuroimage 2013;80:125–43. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.05.057.

[13] Bammer R, Markl M, Barnett A, Acar B, Alley MT, Pelc NJ, et al. Analysis and generalized correction of the effect of spatial gradient field distortions in diffusion-weighted imaging. Magn Reson Med 2003;50:560–9. doi:10.1002/mrm.10545.

[14] Mesri HY, David S, Viergever MA, Leemans A. The adverse effect of gradient nonlinearities on diffusion MRI: From voxels to group studies. Neuroimage 2019:116127. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2019.116127.

[15] Winkler AM, Ridgway GR, Webster MA, Smith SM, Nichols TE. Permutation inference for the general linear model. Neuroimage 2014;92:381–97. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2014.01.060.

[16] Eklund A, Nichols TE, Knutsson H. Cluster failure: Why fMRI inferences for spatial extent have inflated false-positive rates. Proc Natl Acad Sci 2016;113:7900–5. doi:10.1073/pnas.1602413113.

[17] Nichols T, Holmes A. Nonparametric Permutation Tests for Functional Neuroimaging. Hum Brain Funct Second Ed 2003;25:887–910. doi:10.1016/B978-012264841-0/50048-2.

[18] Holmes AP, Blair RC, Watson JDG, Ford I. Nonparametric analysis of statistic images from functional mapping experiments. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 1996;16:7–22. doi:10.1097/00004647-199601000-00002.

[19] Winkler AM, Ridgway GR, Douaud G, Nichols TE, Smith SM. Faster permutation inference in brain imaging. Neuroimage 2016;141:502–16. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2016.05.068.

[20] Smith SM, Nichols TE. Threshold-free cluster enhancement: Addressing problems of smoothing, threshold dependence and localisation in cluster inference. Neuroimage 2009;44:83–98. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.03.061.

[21] Bava S, Boucquey V, Goldenberg D, Thayer RE, Ward M, Jacobus J, et al. Sex differences in adolescent white matter architecture. Brain Res 2011;1375:41–8. doi:10.1016/j.brainres.2010.12.051.

[22] Kanaan RA, Allin M, Picchioni M, Barker GJ, Daly E, Shergill SS, et al. Gender differences in white matter microstructure. PLoS One 2012;7. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0038272.

Figures