3018

Effect of nighttime wakefulness on the brain's structure and function: a study involving virtual ISMRM2021 attendees1Laboratory for Biomarker Imaging Science, Hokkaido University Graduate School of Biomedical Science and Engineering, Sapporo, Japan, 2Department of Functioning and Disability, Hokkaido University Faculty of Health Sciences, Sapporo, Japan, 3Siemens Healthcare K.K., Tokyo, Japan, 4Global Center for Biomedical Science and Engineering, Hokkaido University Faculty of Medicine, Sapporo, Japan

Synopsis

Keywords: Neurofluids, Brain, sleep, jet lag, glymphatic system, metabolite, cognition, functional connectivity

Little had been reported about the effect of nighttime awakening (virtual jet lag) on the brain structure and function. In this prospective study which evaluated if short-time nighttime awakening due to virtual conference attendance affected the brain function, increased sleepiness, impaired information-processing ability, decreased mALPS index to suggest impaired glymphatic system functioning, a trend toward altered functional connectivity, were observed after nighttime awakening. The finding on mALPS index was similar to true jet lag.Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic withheld transcontinental travel. Consequently, there was an abrupt increase in virtual conferences, of which ISMRM2021 and RSNA2021 were no exceptions. Virtual meetings in different time zones demand nighttime awakening, which can cause jet lag-like symptoms, a condition known as virtual jet lag. Circadian rhythm disturbances associated with jetlag or shift work adversely affect cognitive performance and brain structure and function, as evident by MRI1-3. A volumetric study on airline crews and shift workers has shown decreased regional brain volume1. Resting-state functional MRI (rsfMRI) has shown altered functional connectivity (FC) in several brain regions in travelers under jetlag2. Very little has been explored about the effect of virtual jet lag on brain structure and function. In this prospective study, we aimed to evaluate if short-time nighttime awakening due to virtual conference attendance affected brain function.Materials and methods

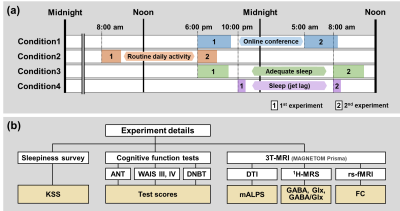

Fourteen daytime workers who attended ISMRM2021 or RSNA2021 virtually and consented to the study were enrolled. The study protocol (Fig 1) consisted of Karolinska Sleepiness Scale (KSS) to assess the degree of sleepiness, neurocognitive function tests {i.e., Attention Network Task (ANT), Double-N Back Test (DNBT), and Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (WAIS)-III and IV} to determine concentration and attention, FC by rsfMRI to assess altered brain function, 1H+MRS to evaluate any perturbations in neurotransmitter release particularly GABA and glutamate (Glx), and modified DTI analysis along perivascular space (mALPS) index by DTI to determine the glymphatic system functioning4-5. MRI was conducted using a 3T scanner. The major scan parameters were: TR/TE= 3000/30 ms and 140 dynamic scans for rsfMRI; TR/TE= 3000/68 ms and 40x35x20 mm3 at anterior cingulate for 1H+MRS; and TR/TE= 5000/43 ms, b=700 s/mm2, and 20 MPG directions for DTI. FC was derived using ROI-to-ROI analysis of CONN toolbox, taking default mode network (DMN) as the seed ROI. GABA, Glx, and GABA/Glx were calculated using Gannet. mALPS was calculated from Dxx, Dyy, Dzz of DTI, using Dr.View software. During ISMRM2021or RSNA2021, the volunteers actively attended the meetings from 10 pm through 5 am local time (UTC+9 hours) and remained awake [Condition 1]. They were allowed to have enough sleep before the event. The evaluation, i.e., the level of sleepiness, neurocognitive function tests, and MRI, was done before and after the virtual meeting. To differentiate the results from daily fluctuations, the volunteers underwent the evaluation before and after daily routine work [Condition 2] and before and after bed (n=7) [Condition 3]. To determine whether the virtual jet lag was affected in the same way as actual jet lag, one of the volunteers who attended ISMRM2022 (UTC) and QMR2022 (UTC+1 hour) in person undertook the evaluation in the evening after returning from the trip and the following morning [Condition 4]. Paired t- or Wilcoxon signed-rank tests were used to determine a difference between evaluations [Conditions 1-3]. Partial correlation analysis was also performed to determine a relationship between cognitive performance and the MRI indices. In all conditions, corrected P <0.05 was considered statistically significant.Results

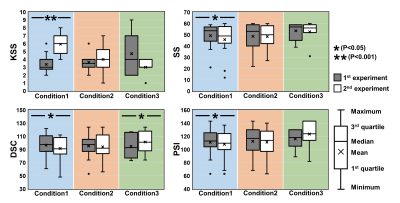

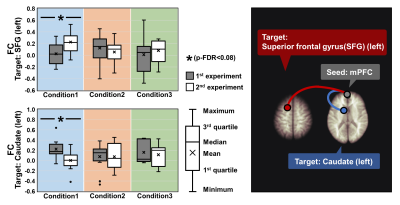

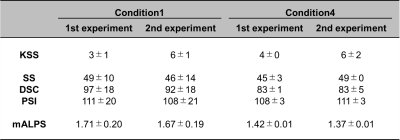

The KSS significantly increased after nighttime wakefulness, as was a significant decrease in digit symbol coding (DSC), symbol search (SS), and processing speed index (PSI) of WAIS-III and IV test scores (Fig 2) [Condition 1]. The mALPS index also significantly decreased after nighttime wakefulness (Fig 3). FC between DMN and left superior frontal gyrus (SFG) tended to increase, but that between DMN and the left caudate tended to decrease (Fig 4). FC between DMN and the left SFG showed a significant moderate positive correlation with KSS (r= 0.542). No significant difference was observed in the evaluation parameters for Condition 2. However, for Condition 3, the DSC test score after the bed was significantly higher than that before the bed (Fig 2). As for Condition 4, an increase in the KSS and SS and PSI test scores and a decrease in the mALPS index were noted, in the following morning (Table 1).Discussion

A decrease in DSC, SS, and PSI suggests impaired information-processing ability. From the observations of Condition 1, it can be taken that increased sleepiness after nighttime wakefulness impairs information-processing ability. The decrease in the mALPS index is in alignment with previous reports6-7. Nighttime waking decreases perivascular system diffusivity and impairs the brain's waste excretion system functioning. A tendency toward increased FC between DMN and left SFG may indicate the brain's attempts to sustain the information-processing ability. Failure to observe a difference in GABA or Glx may be due to a more dynamic nature of neurotransmitter discharge or insufficient temporal resolution. The lack of significant difference in the evaluation parameters for Condition 2 implies that routine daily work affects very little on cognitive performance and brain function and that the observations of Condition 1 are due to short-term nighttime waking. Improved DSC score after bed in Condition 3 may indicate the importance of adequate sleep for enhanced cognitive performance. Although lacking statistical proof, the observations of Condition 4 suggest that jet lag-impaired brain function recovers more rapidly than the recovery of the glymphatic system.Conclusion

Nighttime wakefulness can sufficiently impair the information-processing ability and the functioning of the glymphatic system.Acknowledgements

No acknowledgement found.

References

1. Cho K. Chronic 'jet lag' produces temporal lobe atrophy and spatial cognitive deficits. Nat Neurosci. 2001;4(6):567-568.

2. Zhang F, Li W, Li H, et al. The effect of jet lag on the human brain: A neuroimaging study. Hum Brain Mapp. 2020;41(9):2281-2291.

3. Kakeda S, Korogi Y, Moriya J, et al. Influence of work shift on glutamic acid and gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA): evaluation with proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy at 3T. Psychiatry Res. 2011;192(1):55-59.

4. Zhang W, Zhou Y, Wang J, et al. Glymphatic clearance function in patients with cerebral small vessel disease. Neuroimage. 2021;238:118257.

5. Taoka T, Masutani Y, Kawai H, et al. Evaluation of glymphatic system activity with the diffusion MR technique: diffusion tensor image analysis along the perivascular space (DTI-ALPS) in Alzheimer's disease cases. Jpn J Radiol. 2017;35(4):172-178.

6. Bernardi G, Cecchetti L, Siclari F, et al. Sleep reverts changes in human gray and white matter caused by wake-dependent training. Neuroimage. 2016;129:367-377.

7. Elvsåshagen T, Norbom LB, Pedersen PØ, et al. Widespread changes in white matter microstructure after a day of waking and sleep deprivation. PLoS One. 2015;10(5):e0127351.

Figures